My World in Paper: A Personal Look at How E-books Alter Our Reading Experience

At an early age I learned that magic was real.

I was only a toddler when black and white squiggles on a page morphed into symbols that somehow turned into sentences which turned into stories. The sound of crinkling pages was just so satisfying.

Some books were printed on old-fashioned papyrus on which you could feel every wrinkle and crease. Others had gold leaf edging, smooth and sleek, and others still had jagged, rough-cut edges. Yes, even the smell of aging paper was entrancing.

Books are a part of our childhood — an important part since they are usually the first objects that introduce us to the world!

Now electronic books have entered the public sphere and are practically as common as print.

No crinkling pages. No rough-cut edges. No scent of years past.

And that matters. Research and my own experience show that reading from electronic books just doesn’t engage our senses or come close to matching the quality, connection, and intellectual stimulation that physical books provide.

Influenced by my mother, I grew up living between the pages of musky scented print.

My mother was my first teacher who taught me to read, as she did for hundreds of school kids in her 34 years of teaching. As a special education teacher in inner-city Reading, Pennsylvania, she witnessed the intellectual struggles her elementary-aged students faced every single day.

Those same students, however, found comfort in stories. One must understand that special education children, especially those with less than supportive homes, have little to inspire them. Books become a saving grace.

Sometimes I would go into class with my mom and read to her students at story time. The Magic Tree House series by Mary Pope Osborne was a favorite. Where else could they go on adventures riding on dinosaurs, exploring deep oceans, or encountering sabertooth tigers with flashing teeth and claws? Reading aloud, I could see Osborne’s words casting a spell over those kids as they sat in their seats, entranced.

When it wasn’t a Magic Tree House day, I’d read children’s books from my own bookshelf. These beloved books I passed around so the children could run their fingers over the pictures and turn the pages themselves. When I observed my mom teaching she would sometimes trace her students’ hands along each word and help them pronounce it.

Later I’d learn that Mom’s method was good practice.

Both seeing and physically touching printed words on a page is proved to help readers pronounce words and remember their meaning.

After my mom’s retirement, I saw students reading more on electronic tablets, and I worried that without seeing words on a printed page and running their fingers across hardcopy, those early readers were losing something valuable.

As it turns out, my fears weren’t unfounded. An article by Ferris Jabr published in Scientific American examines this relationship between the way we read on paper versus screens. “’There is physicality in reading,’” says developmental psychologist and cognitive scientist Maryanne Wolf of Tufts University, “‘maybe even more than we want to think about as we lurch into digital reading—as we move forward perhaps with too little reflection.’”

The way we experience the text influences how we retain information on print versus screen. “Evidence from laboratory experiments, polls and consumer reports indicates that modern screens and e-readers fail to adequately recreate certain tactile experiences of reading on paper that many people miss and, more importantly, prevent people from navigating long texts in an intuitive and satisfying way. In turn, such navigational difficulties may subtly inhibit reading comprehension,” writes Jabr.

While it is important to incorporate modern technology into the classroom, technology itself should not be the default means of teaching a child to read. Print books are essential to a child’s learning because print allows for children to grasp the meaning behind literary symbols.

The 2003 scholarly article,“The Essentials of Early Literacy Instruction,” states that “Young children’s grasp of print as a tool for making meaning and as a way to communicate combines both oral and written language. Children draw and scribble and ‘read’ their marks by attributing meaning to them through their talk and action. They listen to stories read aloud and learn how to orient their bodies and minds to the technicalities of books and print.”

When reading on a Kindle or other e-reader, the cognitive connection is not the same. With print, children can write in the margins of books, earmark pages, draw arrows and scribbles, and highlight. Interacting physically with a page incorporates more of the senses and increases a reader’s connection to print as a bridge between oral and written language.

In these ways, print books are simply better than their electronic counterparts at conveying information. When we can write on and physically interact with a printed version as opposed to a screen our brains must focus more on the text instead of mindlessly scrolling, thus increasing memory retention. We essentially allow ourselves to dive straight into the page.

A study reported on in the Guardian in 2014 found that readers using a Kindle were less likely to recall events in a mystery novel than people who read the same novel in print. Reading on the printed page helped them remember events and not become distracted by apps, music, or other features found on e-readers.

On a printed page, the students in my mom’s class learned that every squiggle represented a letter and that letters combine with other letters to create words. Then, students could write in their own workbooks and trace the letters for themselves.

Clicking through computer programs or matching letters on a screen is only one level of learning. Students cognitively retain more when they engage in the act of physically writing, which I saw in the progress that my mom’s students made.

Not only does physically interacting with printed books enhance a reader’s memory, it’s also better for their health.

Countless studies have shown that the blue light emitted by a screen can damage one’s eyes. Blue light disrupts a body’s circadian rhythm, the body’s natural wake/sleep cycle, leaving one groggy and irritable and resulting in a reduced amount of time in REM (rapid eye movement) sleep.

The reason is a reduced secretion of melatonin, the hormone that induces sleepiness. Researchers at the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston have found evidence that the more blue light from a screen that readers are exposed to, the more likely they are to develop breast cancer, colorectal cancer and prostate cancer.

Limiting blue light exposure is especially important to the health of young children, when developing a regular sleep pattern is essential, and the use of electronics before bed — including reading stories on an electronic device — may hinder their ability to develop a regular circadian rhythm.

Besides, how can reading from a cold, flat object like a Kindle compare to sitting on a parent’s or sibling’s lap before bedtime, snuggled in soft towels after a nice warm bath and pointing to the glimmering scales of The Rainbow Fish or the classic colorful tales by Eric Carle like The Mixed-Up Chameleon?

Physical connections to books ground our imaginations in the real world. Anything we dream can become a reality, as shown through the pages of a book.

One of my first memories of books is of my mother’s hands. They were hands that wrote elegant, flowing cursive script, hands that turned page after page, leafing through the books of my childhood, like Goodnight Moon, Corduroy, and The Giving Tree.

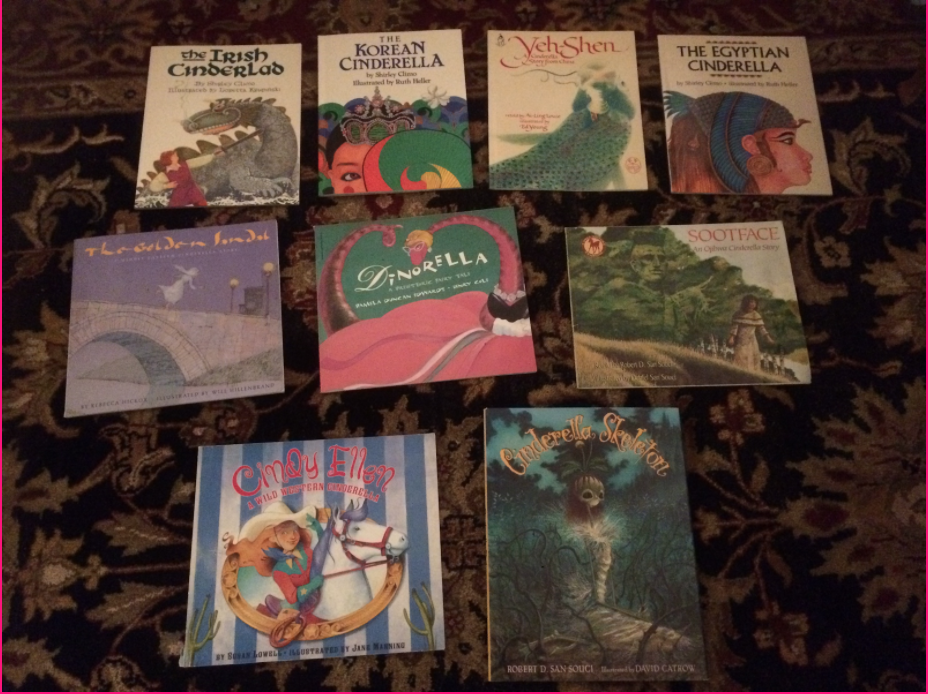

My mom would spend hours upon hours reading to me on my bedroom floor, surrounded by the castle walls of my stories, their pages majestic banners. My collection of Cinderella stories from around the world had their special place on the top shelf. When she read to me Yeh-Shen, The Egyptian Cinderella, The Korean Cinderella, Cinderella Skeleton, Dinorella, Cindy-Ellen, The Golden Sandal, and The Irish Cinderlad, I felt like a fairytale princess myself, twirling around and around with my silver, star-tipped magic wand.

Next came Paul O. Zelinsky’s Rapunzel and Lisbeth Zwerger’s Little Mermaid, both more beautifully illustrated than any other classic princess stories I knew. I liked these more than the Disney versions, and I asked my mother to read them often. The Seven Chinese Brothers and The Velveteen Rabbit followed. The Lupine Lady, Where the Wild Things Are, Love You Forever, The Snowy Day, Albert, The Runaway Bunny, Stone Soup, and The Story of Babar were all portals to a more magical world.

Each story lasted for what felt like hours spent in the most magical worlds. I sat hypnotized by the words on the page and the stories that my mother read. I helped her turn the pages, sometimes even pointing out my favorite parts. She took my fingers, raised them to her lips, and kissed them before returning us to the world of make-believe.

Joyce Hinnefeld • Sep 29, 2017 at 5:42 pm

Beautiful, Sara!

Sara Weidner • Sep 30, 2017 at 4:47 pm

Thank you Dr. Hinnefeld!! 🙂