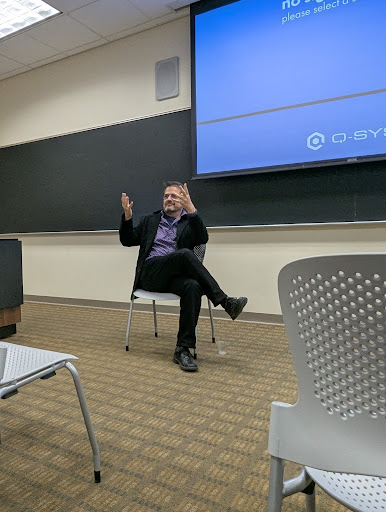

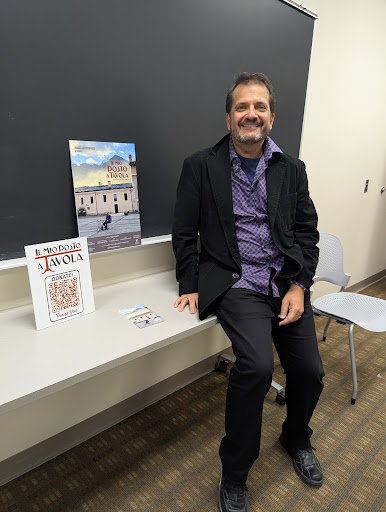

As Thanksgiving rolls around the bend, stories of transnational cooperation, images of turkeys, cornucopias, and peaceful gatherings tend to flow into one’s mind. However, the true story of Thanksgiving caters to an exploitative, sanitized, pro-status quo agenda that often ignores the realities of this history. Dr. Jamie Paxton, Associate Professor of History, who studies Indigenous culture, specifically the Mohawk people and their interactions with European settlers in Native North America, provides some context on this misrepresented history.

Why/when was Thanksgiving declared a holiday?

Colonists occasionally declared days of thanksgiving and prayer to celebrate good fortune or avert calamity. These days were religious occasions confined mainly to New England and were characterized by fasting, not feasting.

The Thanksgiving we celebrate has more to do with the American Civil War than it does [with] seventeenth-century Pilgrims. In the midst of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln announced that the last Thursday in November would be set aside for a day of thanksgiving to promote unity in a badly divided nation.

It was around this time that Thanksgiving became associated with the 1621 feast in Plymouth Colony between English colonists and Wampanoags. Edward Winslow’s account of that feast was not published until the 1840s. Before then people made no connection between Thanksgiving and the Pilgrims.

Thanksgiving remained a regional holiday until the late nineteenth century. White Southerners, not keen to celebrate an event associated with New England, ignored the holiday. Western states were uneasy with a holiday featuring Indigenous people so prominently at a time when many Western tribes remained powerful and forcefully defended their lands and independence.

By the end of the 1800s, however, circumstances had changed and Americans embraced Thanksgiving. By then, most tribes had been forced safely onto reservations, and Americans were becoming nostalgic for the “vanishing Indian.” At the same time, growing concern about the number of Catholic and Jewish immigrants entering the country led many to embrace the English-speaking, Protestant Pilgrims as a way to impose cultural hegemony.

Can you briefly describe the concept of “Truthsgiving,” and what it has done or intends to do?

Truthsgiving, as I understand it, seeks to decolonize Thanksgiving by telling fuller, more complicated histories of this country, celebrating Indigenous cultures, and working to bring to light and ameliorate the conditions on many reservations. In that sense, it is not doing anything new.

Indigenous people have long pushed back against sanitized versions of history. On Thanksgiving Day in 1970, at the height of the Red Power Movement, Wampanoags occupied Plymouth Rock and announced a National Day of Mourning. Insisting that Americans needed to learn the history of genocide and dispossession, they turned the National Day of Mourning became an annual event. Truthsgiving builds on and broadens that tradition.

How and why did the peace between the Wampanoag and the English end?

That is a long, complicated history about which historians have written many books. The brief version is that English attitudes were shaped by beliefs that America was a wilderness inhabited by savages who were under the sway of the devil. After European diseases decimated Indigenous populations, the number of English colonists grew rapidly after 1630.

As colonists pushed settlements aggressively onto Indigenous lands, violent conflicts erupted, and the balance of power shifted decisively in favor of the English. Some Wampanoags converted to Christianity in response to their healers’ inability to cure smallpox and measles, while many others resisted. King Philip’s War in 1676 was an unsuccessful attempt to create a coalition of tribes powerful enough to drive the English off the continent.

What do you believe is the largest misconception regarding the holiday?

I don’t think many people are aware of how Thanksgiving is implicated in nation-building narratives that contribute to the erasure of Indigenous people from the past and present. That may sound like an odd thing to say about a holiday that so prominently features Indigenous people, but I think one reason that Americans find Thanksgiving acceptable is that it legitimizes settler colonialism and their right to the land.

The participation of the Wampanoags in the harvest feast implies they welcomed a permanent English presence on their lands. Then, once the meal had been consumed, the Wampanoags conveniently fell out of the story and out of popular imagination. Their role, it seems, was to present America as a gift to the newcomers and then walk off the stage.

The Thanksgiving story gives the impression that the Wampanoags consented to colonization and contributes to the erasure of Indigenous people from history. The history preceding and following the first Thanksgiving tell a quite different story, but it is not a story that has entered popular memory.

What actually happened on the day Thanksgiving is based on?

Two accounts describe the harvest festival that took place between the Plymouth colonists and the Wampanoags that later became linked to modern Thanksgiving. Edward Winslow wrote the more detailed of the two, but it remained largely unknown until it was published in the 1840s. Here it is in full.

“Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help, served the company almost a week.

At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, and many of the Indians came amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it is not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”

Edward Winslow’s account appears in Heath, Dwight, A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth: Mourt’s Relation (1963); EyeWitness to America (1997); Morrison, Samuel Eliot, Builders of the Bay Colony (1930).

Why, and/or how do you think this narrative shifted away from the truth?

While I agree that the stories we associate with Thanksgiving are badly distorted, there is no one true story of Thanksgiving. We can tell the story in a way that makes Wampanoag’s victims of settler colonialism. We can also tell the Thanksgiving story in a way that emphasizes Wampanoag’s agency and power.

In the years before the 1621 feast, the Wampanoags were trying to incorporate the English into an Indigenous-led coalition against their traditional enemies the Narragansetts. In that context, that first gathering was part of that larger strategy to foster alliances and acquire European goods that would give the Wampanoags an advantage over their neighbors.

Isolating Winslow’s account from its context, however, allows the past to be used or misused for present purposes. Lincoln needed a nation-building holiday to bring the country together. Many late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Americans wanted the holiday to buttress their claims to superiority by defining America as a white, Protestant nation.

The stories people tell about Thanksgiving say a lot more about them than they do about seventeenth-century Wampanoags and colonists. The history of memory is a fascinating subfield of history that analyzes how and why people remember (and forget) the past the way they do to either challenge or preserve the status quo.

If you want to read further about the Wampanoags, English, and Thanksgiving, I recommend David J. Silverman’s This Land Is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving.

Javen • Nov 20, 2023 at 12:13 pm

Everything I knew abt thanksgiving was from the Charlie Brown special. Glad you are shedding some light on this Liz