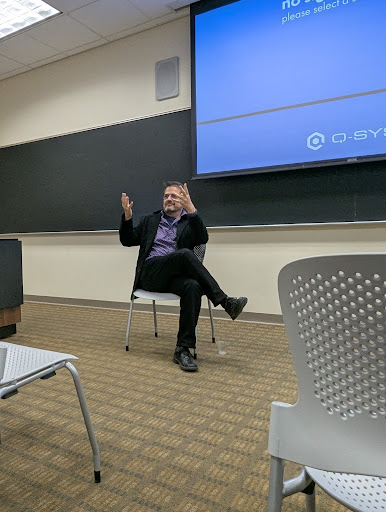

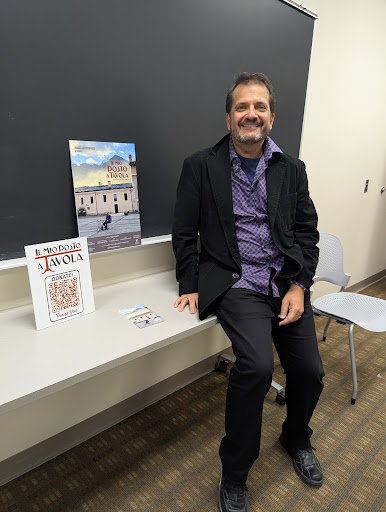

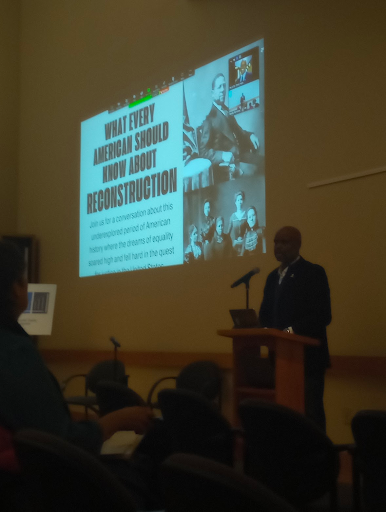

On Wednesday, February 7th, the Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) held an in-depth conversation on the Reconstruction period and its relevance today. Led by Vice President and Dean of Equity and Inclusion, Dr. Chris Hunt, the talk summarized how this brief yet potent epoch in Black history stood in the American canon and how it correlates to our modern social climate.

Following the end of the Civil War, The (Radical) Reconstruction period augmented social, economic, and legislative positions for newly freed Black people. During this time, Black politicians came into power in the South, creating state-funded school systems and establishing economic equity. From 1865 to 1872, an agency called The Freedmen’s Bureau provided aid and security to newly freed individuals. Additionally, the 14th and 15th Amendments were passed, providing equal citizenship and African men the right to vote, respectively. However, this period came to an end due to the Compromise of 1877; following this, Jim Crow laws were introduced and heavily enforced.

Hunt initiated the discussion by describing Virginia history textbooks, which taught children “history in distortion.” These textbooks portrayed slaves as willfully subservient, having benefitted from their enslavement. Although biased and incorrect, this perspective has been weaponized by politicians like Ron DeSantis, who wish to change curriculums to instead show how “enslaved people ‘developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.’”

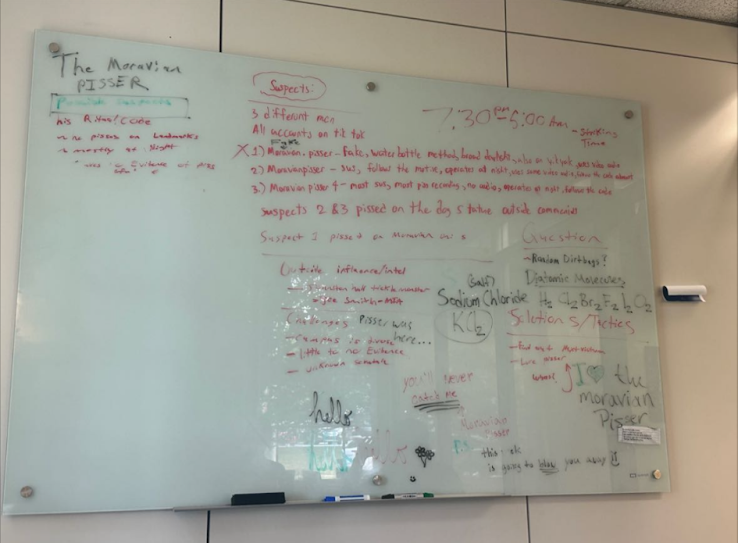

Hunt reflected on this power structure and, quoting George Orwell, stated, “Who controls the past controls the future.” That is, those in power can warp narratives of the past and change the future. In his words, the discussion served as a “counter-narrative” against the misinformation and turned to critical race theory to talk about Reconstruction and why it is essential to study today. He showed audience members a Crash Course video on Reconstruction before asking panelists to comment on it.

This conversation was sponsored by the English and history departments; panelists included English associate professor Dr. Waller-Peterson, associate history professor Dr. Paxton, associate history professor, and women’s gender and sexuality department chair Dr. Berger, and Professor Sholomo-Levy from Northampton Community College.

When Hunt first asked about the Crash Course video, Waller-Peterson directed audience members to the slave narratives of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Ann Jacobs as integral to learning the generational struggle of African Americans. She condemned the idea of enslavement being a beneficial system and how we need to be “mindful” when it comes to teaching history that can be warped.

Sholomo-Levy joined in by citing how public media misconstrues the public history of slavery and Reconstruction, using the silent film Birth Of A Nation as an example. The film depicted Black people as extremely violent and hateful. He then asked why America continues to spread racialized misinformation or be ignorant of its history, especially in contemporary politics. For example, presidential candidate Nikki Haley, when asked about what caused the Civil War, failed to give a straightforward answer.

Berger addressed how Birth Of A Nation depicted Black people as brutish and Black men as predatory towards white women. Organizations like the NAACP were vocal against racist depictions and sympathy for the Klu Klux Klan. The publicity resulted in journalists like Ida B. Wells condemning the film and its false narratives that taint history.

Then, Paxton contributed to the conversation by describing how Black agency during Reconstruction was not discussed as much as it should be. Elaborating more on this, he mentioned how enslaved people pushed heavily for the Emancipation Proclamation. Finally, he noted how we tend to overlook the Black communities that should be credited for the Reconstruction.

Regarding government, Hunt explained Black people’s role and how they were able to “rise to high points in government.” He asked panelists how an evolution could take place in such a short amount of time. To answer, Waller-Peterson described how Black people at the time were advocating through literature and culture, even during slavery. Individuals like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth escaped enslavement and, in turn, were vocally fighting against slavery. Other figures like David Walker wrote about the history of slavery and the generational suffering of chattel slavery.

Turning to history, Sholomo-Levy discussed how Lincoln advocated for the “new birth of freedom” in America. During the Civil War, this meant remaking the nation without slavery and expanding justice; this also meant codifying the Reconstruction amendments to expand legal citizenship.

Paxton also explained Lincoln’s legacy and radical vision for Reconstruction. He mentioned representation through the Ten Percent Plan, which aimed to further emancipation. As stated before, the Reconstruction amendments changed the government with Black legislation; white Southerners framed this change as an act of communism.

Hunt explicated the idea of progress and backlash, asking panelists to cite examples of this dichotomy during Reconstruction. Like Berger, Waller-Peterson mentioned Ida B. Wells, specifically her 1895 pamphlet, the Red Record, which highlighted violence and lynching. The document emphasized the backlash that Black men faced as being perceived as predators, especially when they gained the right to vote.

When it came to political power, Berger elucidated how Black people and their right to vote also allowed them to establish themselves through economic means. They faced backlash from white people who did not want their land taken away. The industrializing South allowed Jim Crow laws to be established and let white supremacy foster an “economic status quo.”

Dr. Anderson, assistant professor in public history, joined the discussion by describing anti-black repression of black mobilization – associated with the 1960s Black Power Movement – which was spurred by “Black assertions of equality.” Moreover, he emphasizes observing the exploitation of Black people through action and re-action and dissecting the subtle forms of racism like predatory bank loans of the 1990s.

When it was time for audience members to ask questions, one question was raised about black women during Reconstruction and why we didn’t talk enough about the sexual exploitation and vulnerability they faced, mentioning the slave narrative of Harriet Ann Jacobs. Waller-Peterson answered this by stating that the role Black women played historically in building the nation needs to always enter the conversation.

She expanded on Jacob’s narrative, citing that Black women add new conversations and perspectives. Moreover, she illustrated how Jacob used a pseudonym and hid her identity when writing to talk about issues of sexuality to show the sexual abuse Black girls go through at an early age. On Black girls particularly, she stated how they were not considered girls but as property under chattel slavery with no protections. This speaks not only to the taboo nature of sex at the time but to the sexualization of Black female bodies as well. Finally, she noted the Black women such as Alice Dunbar Nelson, who created societies and organizations to advocate for general equality in Black communities.