Have you ever sat at your desk or bed completely dumbfounded and trying to grasp a concept you need to know for class? Have you ever spent hours rigorously reading textbooks, trying to memorize every little detail before a test to no avail?

These are universal experiences for nearly every student. We all have slumps when we have absolutely no motivation to do our schoolwork or just simply don’t understand what was taught in class.

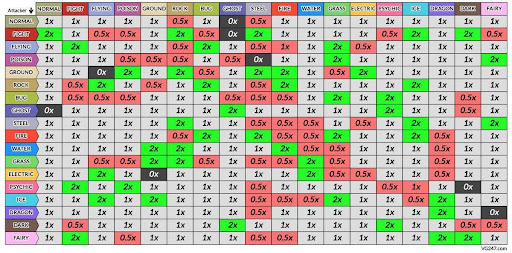

Let’s say a professor says you have to memorize the graph above for the next class. How would you react? I would be willing to guess that you would be viscerally upset. That jerk! How does he expect us to memorize this thing?

Now, what if I told you that this chart is something that 10-year-olds know better than their times tables and animal kingdoms? The Nerds reading this know exactly what this chart is. It is the Pokémon weakness chart.

Snot-shoveling third graders know this like the back of their hand, so why would we, as college students, be so resistant to learning it? It is largely because of the way that we learn this information.

In 1978, psychologists Norman Slamecka and Peter Graf discovered the generation effect. In their study, they found that people remember information better if they generate it themselves rather than being given that information. In essence, this means that you will better remember how to change a lightbulb by actually doing it rather than reading a manual on how to do it.

Much of the reason that iPad kids know this chart better than their times tables is that Pokémon requires them to actively use the information that is given to the player. When you learn something in class, you often don’t have to apply that information until a test or essay. Comparatively, a game will require you to continually apply those lessons immediately and will give you immediate feedback, both positive and negative. A lot of students will study by reviewing notes or highlights, but this is simply not a good way to learn. By skimming over past notes, you are only passively learning.

Studying from what you highlighted in a textbook is essentially like reading a game’s tutorial and then jumping into the final boss. When you study, make sure that you are actively applying what you are trying to learn. Do some practice problems, write out notes, or make flash cards.

Just like games, you need to actively practice the lessons you are taught before you conquer a boss.

Most games are essentially structured like a class. You have your tutorials/lessons throughout, with which you will practice those lessons in relatively easy and low-stakes situations. Later, those skills will be put to the test with bosses/quizzes, which will all eventually culminate in a final boss or exam that puts all your skills to the test.

Games will even mix and build upon concepts that are introduced throughout. At first, you may learn to jump, dash, and attack, but later, you will be required to perform all three within quick succession. It’s similar to how a history class may ask you to connect historical periods or how a statistics course requires you to use the mean and standard deviation to perform a significance test.

Many classes ask students to actively process the material they are learning about, whether it be by doing practice problems, making discussion posts, or writing papers, but many of these classes struggle to truly engage students. So, if games are so similar to classes, then why are they so much easier and more engaging for people to learn?

Part of that is how games offer immediate feedback, whereas most classes do not. When you attempt a boss in Elden Ring, for example, you get instantaneous feedback on whether you did well or not, depending on whether you got killed or not by the boss. Comparatively, students could wait days, weeks, or even months to get feedback for an assignment.

When a player messes up in a battle, they will know exactly what they did wrong because the game punished them for it which then teaches them how to avoid that issue again. This immediate feedback allows the player to continue to improve and advance throughout the game.

Comparatively, the delayed feedback from a class can often leave students in the dark, questioning how well they did, and not knowing what went wrong as the course continues could be detrimental to their learning. While no professor could reasonably provide instantaneous feedback, it’s important to be timely with grading so that students can understand what they did wrong and improve in the future.

Beyond that, the most important difference between school and games is that games allow players to have ownership of their learning, whereas school (typically) does not.

Compared to school, games are completely self-paced. This allows players to approach the game and its lessons as fast or slow as needed. Along with this, players are also given the chance to retry as many times as they want until they “pass.” This trial-and-error design structure means that the player won’t get left behind by the game because it is designed to accommodate people of a variety of skill levels.

Schools have tried to mend this issue for decades, such as with No Child Left Behind but in every instance, they have not only left struggling students behind, but they have left them in the dark. This is because it emphasized getting students out the school doors rather than properly educating them, which inadvertently made a much more one-size-fits-all system.

Games, on the other hand, are not designed with a one-size-fits-all approach but rather an all-sizes-fit-one approach. Games give players the tools they need to succeed, but ultimately, the onus for success is placed on the player. Going back to the generation effect, games require players to take an active role in their learning and allow them to find their own paths to success. There are no rubrics or formulas.

Games obviously have tutorials to introduce their concepts and mechanics, but it is ultimately up to the player to solve the challenges that lie ahead of them. In school, teachers and professors tell students what to learn whereas games give players the tools they need to learn. Giving players that sense of ownership over their actions makes the learning process all the more engaging.

Schools also take that ownership away from students by having permanent consequences. Most of the time, if you take a test, you are stuck with that grade for the rest of that class, which can ultimately determine how well the school perceives you did in that class. Comparatively, games will rarely give permanent consequences to determine whether the player succeeds or not.

Some games will punish the player for narrative decisions they make, such as Baldur’s Gate 3, which will have decisions with reverberating consequences throughout the entire 100+ hour campaign, but they rarely ever will leave the player with game-ending consequences. Playing a game is a process of trial and error that allows gamers to try and try again until they are able to “pass.”

School, on the other hand, is not like that. If you fail or do badly on a test or essay, you typically will not be able to retry like you can in a game. You are just expected to continue with the class and get better grades on future assignments. There are usually no checkpoints to go back to in school.

Some teachers and professors have a contract grading structure that bridges that consequential gap by allowing students to redo and revise assignments until they meet the expectations that are required of them. I won’t pretend to be an expert, but shifting to this grading structure could be pivotal for “gameifying” education by allowing students to demonstrate their learning even if they initially fail to do so.

A lot of schooling has a very isolating quality to it. You can’t talk in class, your work has to be yours alone, and you can’t ask another student for help on a test. Games, even single-player ones, employ an entirely different philosophy. Ian Bogost from the Georgia Institute of Technology describes games as a “community of practice” where players continuously collaborate to overcome challenges.

Whether it be a co-op game where players collaborate to overcome a common obstacle or online message boards like Discord or Reddit, where players ask for help when they get stuck, gamers often overcome the challenges that lie before them by talking and collaborating with others. As much as we make fun of gamers for being smelly shut-ins who haven’t taken a shower since Obama was the president, gamers are incredibly collaborative.

We all know group projects are infamously hated among students, but according to the National Education Association, collaboration helps students develop better interpersonal skills along with better-developing learning and critical thinking skills. More than just projects, it’s important to encourage and develop collaboration both in and out of the classroom between students with discussions, group activities, peer review sessions, and assessments that allow students to work together.

As much as it’s easy to write video games off as silly little toys, they can be a valuable touchstone as to how we can improve the education system and provide better learning outcomes to students. It’s clear that educators are learning to take notes from games in aiding education. A teacher in Alabama recently used the popular game Assassin’s Creed Odyssey to teach his middle school class about the Battle of Thermopylae and many games have started to incorporate educational modes such as Minecraft and Roblox.

Even here at Moravian, games are starting to be used to help teach students concepts that are taught in class. Dr. Samuel Rhodes, in the political science department, recently assigned students a project in Minecraft to demonstrate how political parties overcome collective action problems and how to address those problems. Not only can students take inspiration from games to improve their learning, but so can educators in crafting their classes.

![The Downfall of Taylor Swift: AI, ‘The Life [and Demise] of a Showgirl’](https://comenian.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/unnamed-6-1.jpg)