The sun has been down for four hours, making the floor of the Costa Rican rainforest even darker than usual. For the seven arachnid enthusiasts and scientists here, the work is just beginning, and there’s nowhere else they’d rather be.

They’re carrying black lights, flashlights, forceps, cameras, headlamps, vials, and any other implement they might use to catch the cryptic, nocturnal arachnids they came here for: Opiliones, also known as daddy long legs or harvestmen.

Among the seven were four of Moravian’s own. Leading the expedition was Assistant Professor of Biology, Dr. Daniel Proud. Joining him were three Moravian students: Maria Lubbos ‘26, Cielo Disla ‘25, and Caleb Gunkle ’25.

Team Opiliones at Tapanti National Park. Photo courtesy of Maria Lubbos.

Three Costa Rican arachnid enthusiasts came with them: Carlos Viquez, the country’s most successful arachnologist; Juan-Pablo Hernandez ‘26, a student from the Universidad de Costa Rica; and Gabriela Almengor, a curator at the National Museum of Costa Rica. These adventurers make up Team Opiliones!

Proud has dedicated his career as an evolutionary biologist to understanding these bizarre and under-researched animals, which has often involved dispelling many beliefs, myths, and urban legends surrounding them. The five-word mantra in Prouds’ lab and during the expedition has been: “They are actually not spiders.”

Another common misconception is that these creatures in fact have the most venomous bite, but it’s impossible for them to bite humans. Well, at least one part of this misconception is true. Opiliones can’t bite humans. They don’t have fangs or teeth, but they also don’t have venom, so they are completely harmless to humans. Instead, what they have are two shovel-like appendages that they use to scavenge for food such as plants or dead insects.

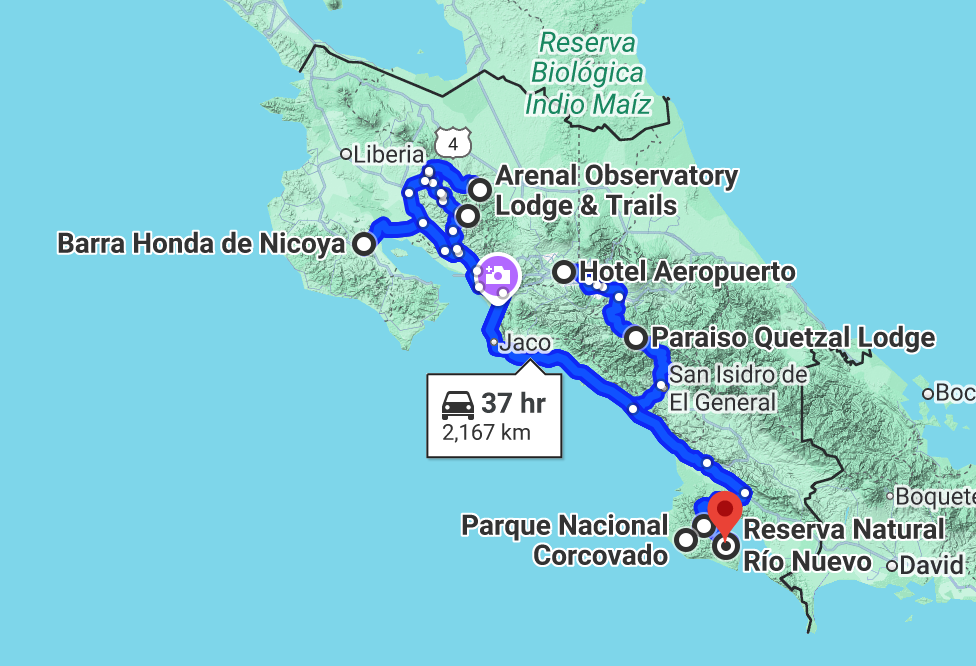

For over two weeks, we traveled throughout the western side of Costa Rica in search of Opiliones. We started by driving to the moist forests of the Talamanca mountains in the northwest of Costa Rica, before heading south and trekking through the remote and almost untouched rainforests in the Osa Peninsula.

We climbed a mountain in Barra Honda and plunged into its deep, damp caves. We then headed east, to Costa Rica’s most prominent Volcano, Volcán Arenal, and the famous Cloud Forest of Monteverde.

The first collection site was 2,700 feet up the Talamancas, at Paraíso de Quetzales, an “eco-lodge” where the main attraction is the surrounding biodiversity. The lodge offered many trails through surrounding forests, including one trail which leads to a scenic waterfall. The lodge had a restaurant with a view and a patio with hummingbird feeders, which attracted more species of hummingbirds to that one place than occur in all of Pennsylvania! Understandably, the lodge is a favorite among birders visiting Costa Rica. The namesake, the Quetzal, probably Costa Rica’s most famous bird, is also often spotted on the property.

Our team took to these trails at night, photographing and collecting the first harvestmen of the expedition. The next day, we set up an impromptu lab in one of the rooms, complete with a microscope, cameras, chocolate, coffee, and many specimens to be photographed and processed.

We later drove on to La Cotinga, a simple but beautiful biological field station surrounded by the remote and dense rainforests of the Osa Peninsula. Here, the winding roads grew more remote, the air hotter, and the roadsides greener. The vegetation slowly became more typically tropical: more palms, coffee farms, large and vine-draped trees filled with epiphytic bromeliads, a flowering plant that grows on trees and orchids. With the lower elevation came more mud, more snakes, more bugs, and hopefully more harvesters to collect.

La Cotinga proved to be a very productive spot, but soon, the team had to pack up. After a couple of days of collecting the team took a beach day, at one of the many breathtaking beaches on Osa.

At Rio Nuevo, to the southwest of La Cotinga, the team met a surprise guest, Coyote Peterson, a popular YouTube wildlife content creator who gets stung and bitten by insects and other animals on purpose and records his reactions. Everyone was surprised to meet him. Peterson is invested in the Rio Nuevo Reserve, he told us, and happened to be in Costa Rica for a conservation summit at the time.

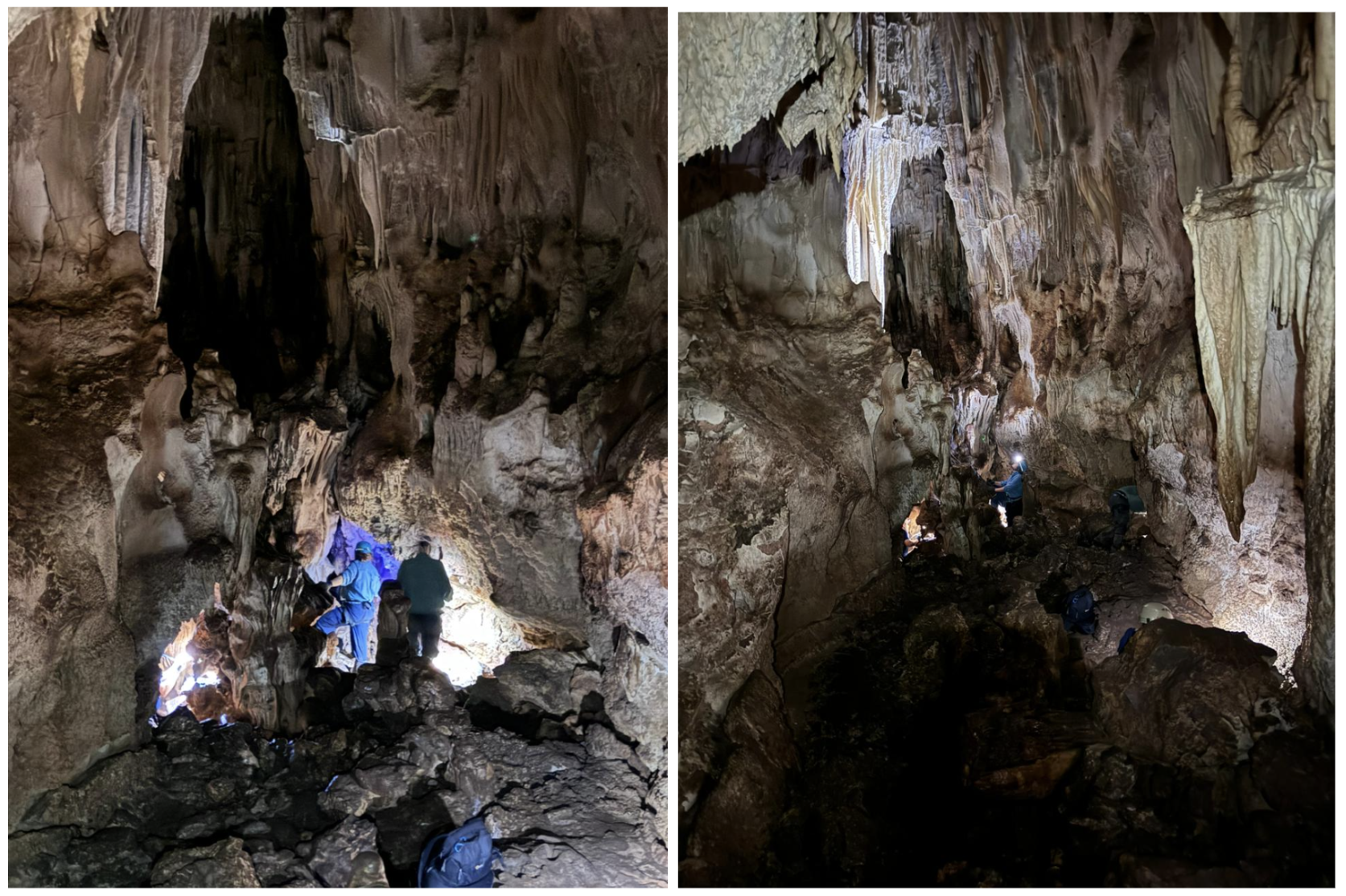

Another day in Osa, the team went to Barra Honda National Park, where we hiked an hour to reach the caves of Barra Honda. Here, we descended a 20-meter ladder to spelunk for harvestmen. There was almost nothing living in the caves, just a three-dimensional maze of rocks to get lost in and a surprising amount of mud. Nonetheless we managed to find two specimens here, one very small harvestmen adapted to live in caves and another kind of arachnid called an Amblypygid, a species that lost its vision as it adapted to the cave ecosystem.

The final spot for the team was Monteverde, a famous cloud forest in Costa Rica and popular tourist destination. A cloud forest is essentially a rainforest but at the same heights as the clouds; in fact, driving there we found ourselves driving through many clouds. This uniquely high precipitation at such a high altitude creates an utterly unique ecosystem.

It was hard to explain to passing tourists why we were here in this beautiful cloud forest, shaking soil in a plastic tray and staring at it. There were so many people approaching, wondering what on earth we were doing, that we eventually needed to start taking turns explaining.

It was amazing to see the excitement of people, some of them hearing about these animals for the first time. When you get to know them they are pretty astounding. Sharing this with people who had never heard of them was one of my favorite parts of the trip. My other favorite part was being able to bushwhack, a bucket list item for me

Me about to bushwhack (left) Me post-bushwhacking (middle) The team sorting litter (right) Photos courtesy of Daniel Proud.

On the last night, returning to the capital, San José, after over two weeks of collecting, we had a delicious home-cooked meal of Chalupas at Pablo’s house where we even managed to collect some Opiliones in his backyard!

The expedition was an undeniable success. By Proud’s estimate, the team encountered, collected, or photographed over 100 species of harvestmen. A majority of these species have yet to be described in the scientific literature. This collection remains in Costa Rica, to be retrieved and exported to Moravian in October.

Once they get it, Proud and his lab plan to extract and analyze the Genomic DNA to find out how they are related and to uncover their evolutionary history. They will be using this information to describe new species and genera or rearrange genera based on their analysis.

This expedition was part of a five-year research project related to Proud’s recent NSF CAREER grant.

Proud plans to make more expeditions in the future. The lab team is currently planning to go to Panama next summer, back to Costa Rica to investigate more remote areas in the Talamanca Mountains the summer after, and to other to-be-determined countries in Central and South America in the summers to follow.

For students who might be interested in traveling to Costa Rica and seeing some of these places, Proud is offering a study abroad course to Costa Rica which leaves in May. He is also always looking for new students who might be interested in doing research. His office is in Collier Hall of Science 323, and he encourages people to reach out over email or meet with him for more information.