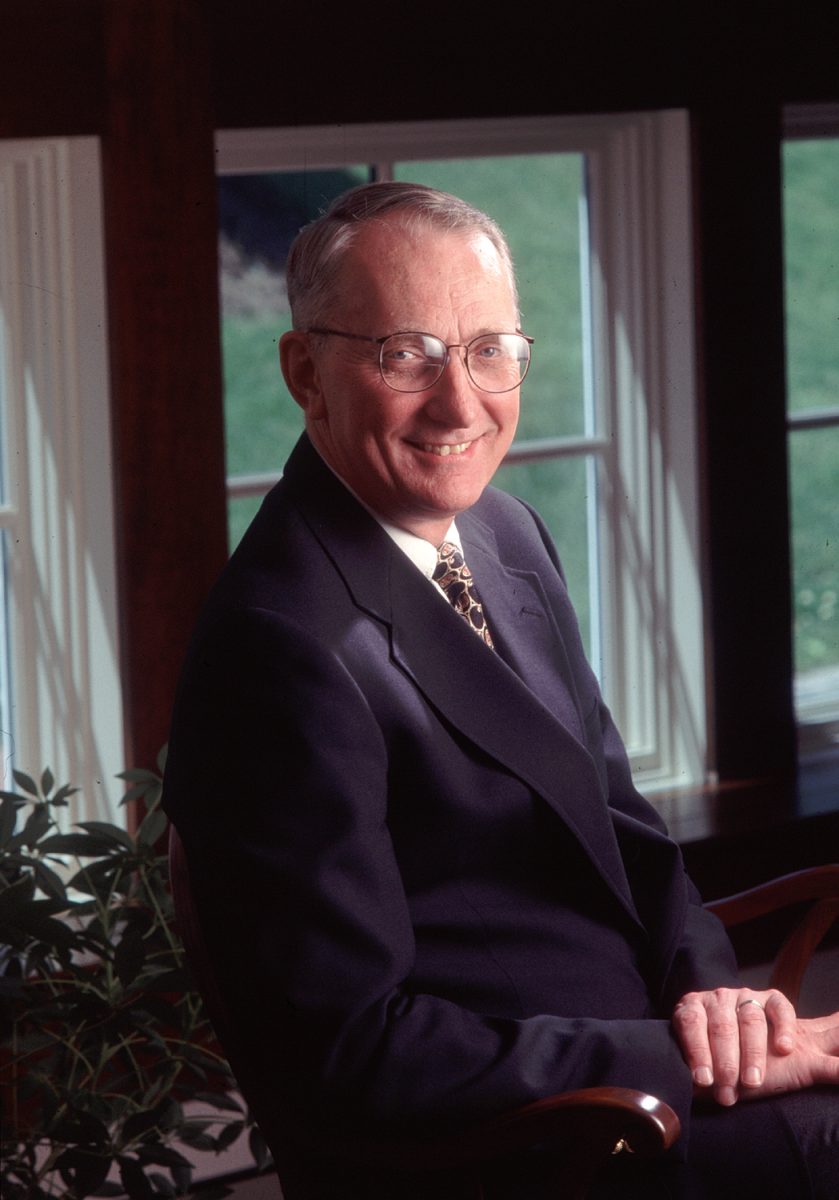

As students reluctantly woke up at 8 a.m. on the first day of the spring semester, the first thing that many of us did was open our phones to look over the syllabi for our upcoming classes so that we knew exactly what to expect for the upcoming months. I and other students of Political Science 293: Political Parties were expecting the course work that’s typically for a class with assistant professor of political science Dr. Samuel Rhodes: lots of readings to discuss, with essays about the content covered in class.

Little did we students know that Rhodes had thrown a curveball into that academic mix. On the first day of class, we discovered that not only would we have the coursework we expected, but we also had a very peculiar semester-long project. We would learn about political parties and how they overcome collective action problems … using Minecraft?

Minecraft is the highest-selling game of all time, with over 300,000,000 units sold. It grew in popularity in the early 2010s because it allowed for copious amounts of self-expression and creative possibilities. It is a survival game that takes place in a highly interactive world made of blocks.

Rhodes is a lifelong gamer. As a kid, he played Doom, Wolfenstein, and Civilization on the computer. Later, however, he began to see games as more than just a pastime.

“When I was in high school, Metal Gear Solid came out, and for the first time, it felt like games could be art and deliver a really powerful political message,” Rhodes said. “I was already interested in politics, even at that time. So that was a nice confluence of things that I was interested in, which was technology and politics.”

When he became a professor, Rhodes hadn’t considered using video games in his classes. However, because Moravian is an Apple Distinguished School, with students all getting an iPad and MacBook, new doors opened for Rhodes to explore games as educational tools.

“’I didn’t really think seriously about using [games] as learning tools until I came here to Moravian,” said Rhodes. But “the barrier to entry [here] is substantially lower than it would be at most other universities.”

The Assignment

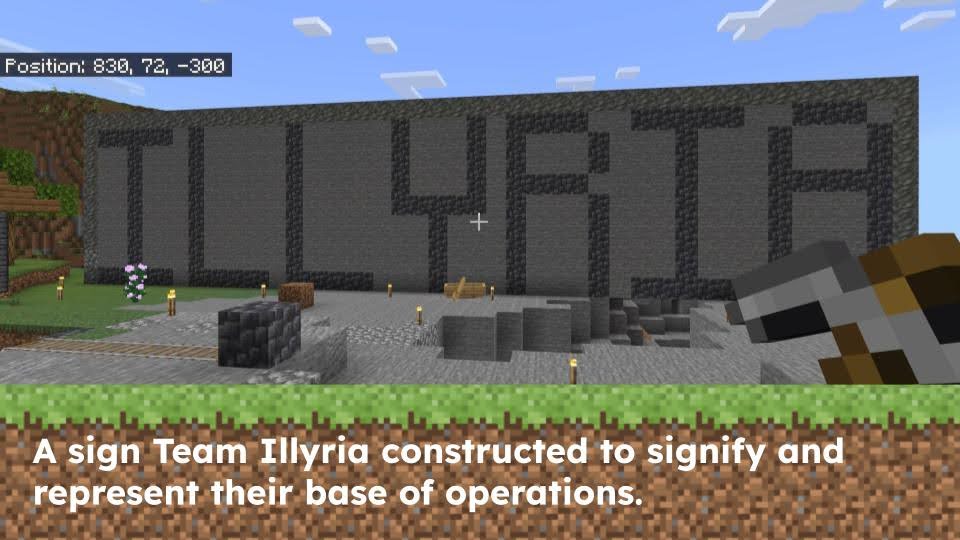

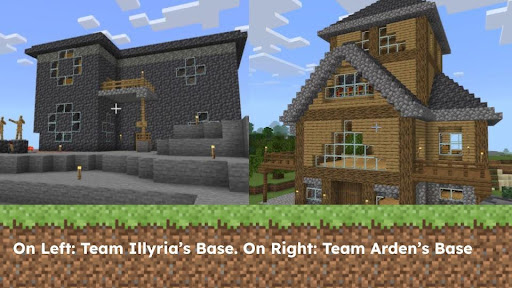

For the Minecraft assignment, the class was split into two groups, Team Arden and Team Ilyria. Each team had to work together towards one common goal: earning more diamonds than the other team. Diamonds are one of the hardest to find and most coveted resources in the game.

This task forced students to apply the theories and concepts discussed in class, such as how parties collectivize and overcome collective action problems, by forcing both groups to compete in ways that are not unlike that of American political parties.

Both groups had to develop democratic governments and organizations to successfully complete this project.

The way they did it, however, varied between the two groups.

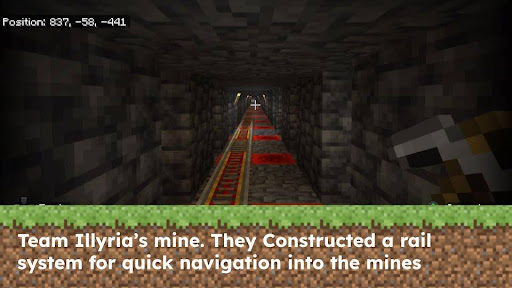

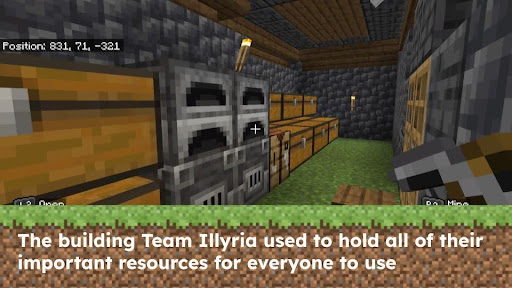

Team Illyria, for example, held election nominations followed by an anonymous vote on Google Forms that would decide a position for every person. They had basic positions, such as president, Jai Fentress ‘25, and vice president, Briana Nigrone ‘24, along with specific positions such as secretary of state, an ambassador to Team Arden, a secretary of agriculture, and a secretary of defense.

Additionally, they used a spreadsheet to maintain a basic accountability system. Each member would input how much time they logged on to the game to ensure everyone pitched in.

The other group, Team Arden, took a more relaxed approach to organizational structure. Our election was comparatively simpler, as Liz Kameen ‘26 and I were immediately elected as president and vice-president respectively due to our experience with the game.

We then organized our group members separated into three different groups: farmers, miners, and managers.

Less experienced players were farmers, since those roles required less mechanical understanding of the game, while the miners were more experienced players who would be able to delve into the dangerous mines.

Managers were in charge of more long-term goals and decisions, such as acquiring an enchanting table and experience farm to make mining more efficient. Additionally, they helped assist the other two groups in their activities.

“The hardest issue for me, especially as one of the leaders of the group, was helping new players learn controls,” Kameen said. “The majority of our group had never played Minecraft before, and we were all playing on different devices, whether that be consoles, phones, or iPads. So I often had to provide a variety of different instructions.”

[LINK to Arden world tour]

Both groups adopted a fluid role system where one person wasn’t confined to one job. If one area needed more help or focus than another, multiple members of each group would pitch in to help.

To ensure both teams were on an equal footing, a poll was done before the groups were decided to gauge the skill levels of each student.

“I tried to evenly distribute the quote-unquote geeks across the two teams,” said Rhodes. “That way you don’t create a lopsided environment.”

Finer Details

As the semester progressed, both groups competed both in and out of the classroom and had to overcome a variety of obstacles.

Team Illyria regularly met as a team over the app Discord so that they could all play together even if it was only for an hour. Team Arden struggled to find times for everyone to meet. We handled most of our business asynchronously by using Discord to provide regular updates about progress.

Team Illyria also suffered from losing a group member who was the primary person in charge of mining, which made the group organize around the issue by assigning new duties to everyone.

In class, wdiscussed how the challenges our teams faced in Minecraft mirrored the problems that political parties face.

In class, wdiscussed how the challenges our teams faced in Minecraft mirrored the problems that political parties face.

“All group activities, political or otherwise, including video games, require the use of solving collective action problems, big or small,” Rhodes said. “Political parties allow groups of activists to get together and try to influence society, at least in government, by capturing seats of power in a democracy that would be elections. So you know, you a microcosm of that could be illustrated in the game like Minecraft.”

After students returned from Spring Break, Rhodes decided to throw another obstacle for each group to overcome: both groups could now go into each other’s worlds and sabotage them. To his surprise, however, by the time class started on the day he made this announcement, both groups agreed to draft a peace treaty that laid ground rules so that neither group would steal or destroy anything.

“It does kind of make sense, right? Two relatively equal powers, not wanting tensions to boil over and try to contain tensions,” said Rhodes. “In essence, a little mini-United Nations, which I totally didn’t expect.”

“It does kind of make sense, right? Two relatively equal powers, not wanting tensions to boil over and try to contain tensions,” said Rhodes. “In essence, a little mini-United Nations, which I totally didn’t expect.”

While the peace was tenuous as both Fentress and Nigrone were advocating for breaking the peace, both groups maintained peaceful relations and even had ambassadors to coordinate with a member of the other group.

The Plot

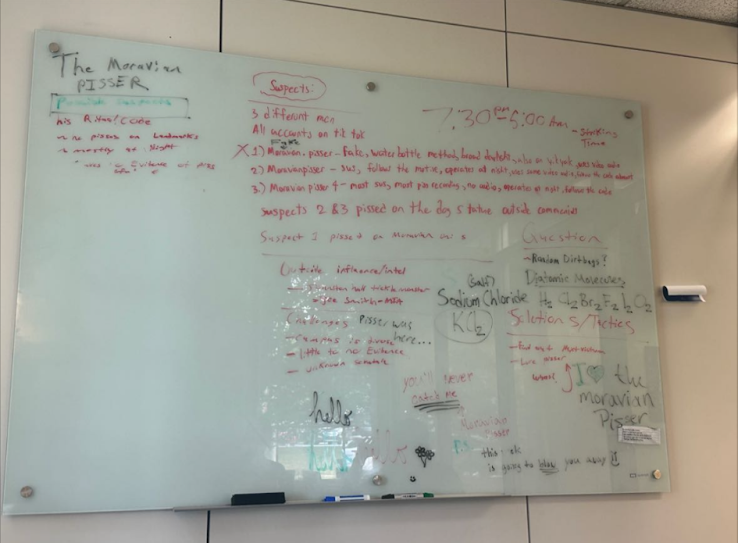

However, a week before both groups were supposed to present, both groups woke up to the worst possible news they could have heard: all of their diamonds had been stolen!

Both groups seemingly lost everything that they had been working toward in an instant. This sent both groups back to square one. After the diamond theft had been discovered, tensions between the two groups immediately rose until they found out that both of their diamonds were stolen. After finding this out, it was clear that one person was responsible for this: Dr. Samuel Rhodes.

At least, that’s what I wanted them to think. In fact, I was the one who stole all of the diamonds from both groups. Liz and I had concocted a scheme where we would attempt a false-flag attack to mobilize both groups into doing one last push to finish strong before the final presentation while giving both groups a common enemy.

This went off without a hitch, to say the least. Both groups jumped to the assumption that Rhodes was the thief and mobilized to respond to that threat. At the same time, it gave Team Arden a protective blanket to prevent attacks in response to stealing the diamonds.

“It’s very creative, which is one of the reasons why I want to use video games as teaching tools, because it’s also teaching me something about how students operate and think beyond the scope of the assignment. It’s a little miniature version of a political universe,” said Rhodes. “Politics is war by other means, and that’s what the Democrats and Republicans are engaged in as they’re trying to outmaneuver one another, to outsmart one another, to find a message or a particular strategy that the other side might not have thought about.”

After the shocking discovery, both groups kicked things into gear to recover from the crippling blow. Team Illyria met together to collectivize their resources and mine as many diamonds as they could within the short period they had. Ultimately, they were able to mine 133 diamonds. Team Arden also banded together to improve their village as much as possible to prepare it for the presentation.

Lessons Learned

Despite who did or did not win, both groups effectively organized and responded to collective action problems in varying ways, which reflected and simulated how political parties respond to issues both concrete and perceived.

“Political parties may seem boring and almost too commonplace to find educationally engaging … that’s until you throw Minecraft into the mixture and see how difficult it truly is to organize an entire group of people for one particular purpose,” said Kameen.

Word circulated around campus about this class, especially within the political science department.

“Oh my god, I wish I was taking that class. That sounds so fun,” said Kelley Davison ‘24

“I thought it was an awesome idea and that Minecraft was the perfect choice for the experiment,” said Matt Connors ‘24. “It’s exciting that video games, something I love, was being used as an academic tool for learning and experimentation. The potential is all right there for video games to act as a teacher or as an environment to facilitate learning.”

As the world of video games continues to expand and evolve, educators across the country have chosen to use games in new and innovative ways to teach students in a variety of disciplines. Students have learned about city planning through Minecraft. A teacher used the game Assassin’s Creed Odyssey to teach his high school class about the Battle of Thermopylae. A professor in Tennessee is teaching a course on Red Dead Redemption II and how that game reflects the period of the late 19th century.

Video games are becoming a more and more common tool in the world of education, and this experiment for the students of POSC 293 lies at the very precipice of the rapidly expanding possibilities that are quickly opening up to educators across the country.

In the future, Rhodes plans to continue to use video games as a supplementary educational tool. Next semester, he plans to craft another Minecraft project for a special topics course on political communication.