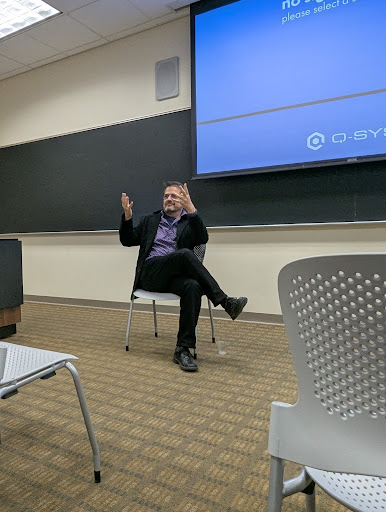

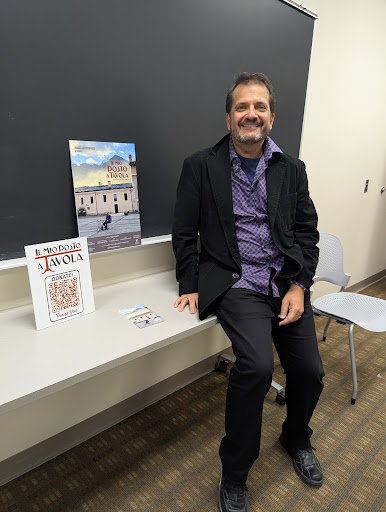

On Friday, April 4, the Bethlehem Area Public Library hosted “Beyond the Great Wall: The China You Don’t Know,” an event focused on taking a humanitarian lens to challenge stereotypes and rethink assumptions about China.

The discussion was moderated by Huijing Wen, associate professor of education at Moravian. Joining her were guest speakers Heng Du, an assistant professor of Chinese at Wellesley College, and Daigengna Duoer, assistant professor of religion at Boston University.

Three Moravian faculty members served as discussants: Dorthee Hou, assistant professor of Chinese and Asian studies; Holly Jo, assistant professor of political science; and Liz Gray, associate professor of English and writing arts.

Duoer opened the panel by saying, “China is not one, but many.”

She used a 3D model to demonstrate China’s ethnic, geographic, and political diversity, highlighting the varied regions: farmlands, mountains, and deserts.

China’s population primarily lives in flatlands, she said, and as the country has expanded, the nation has formed varied cultures, languages, and political identities. Duoer further described the political climate in China, explaining that there are contested areas, including the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of China (Taiwan).

She also mentioned the Mongolian and Tibetan resistance movements and the state’s control over language and education.

Duoer discussed the White Paper Protests of 2022, where Chinese citizens held up blank pieces of paper in front of their faces to protest the Chinese government’s restrictive COVID-19 regulations.

Du followed with a discussion on individuality within Chinese culture that contradicts Western stereotypes of strict collectivism.

She broke down the idea of the individualistic West versus the collective East.

“Individuality is a gift we give to each other,” Du said.

Du spoke about Confucian teachings, recounting the legend of the friendship between Bo Ya and Zhong Ziqi, in which a friend is described as someone “who understands my music” and supports your individual perspectives.

Gray contributed to the conversation through the lens of creative writing. She referenced the book Drunk Tank Pink by Adam Alter, explaining that our environment can subconsciously influence our preconceived notions and stereotypes without a complete understanding of other cultures.

Gray spoke about her own family’s migration from China to Hawai’i and read from one of her recent works.

“How do we combat implicit bias?” Gray asked. “By grounding ourselves in the lives and stories of real individuals.”

Jo took a political science lens to understand China’s political structure and how it responds to diversity. She questioned how minority groups are represented within China’s political system.

“Is minority political participation meaningful if it is overshadowed by state authority?” Jo asked.

Hou brought a comparative perspective to the conversation by drawing parallels between the industrial “rust belts” of China and Bethlehem. She discussed the closing of Bethlehem Steel and the decline of China’s state-run industries in the 1990s.

“It’s important to build bridges and share stories,” she said. “When we start with the idea that China is one monolithic thing, we limit the potential for deeper understanding.”

In the final segment of the talk, audience members asked questions of the panelists, including how individuality can exist within a broader collectivist framework.

Duoer described individuality in terms of jazz music, describing it as “the ultimate form of freedom.”

Duoer also emphasized the importance of education, claiming that it leads to mutual understanding.

“Help each other discover what you want in life,” she said. “Freedom isn’t about taking from others – it’s about creating space for everyone to thrive.”

Du closed the conversation with a reminder that individuality is not exclusive to Western culture, emphasizing that it exists across history, culture, and traditions.

Kin Cheung • Apr 25, 2025 at 12:17 pm

Thanks for reporting on this event! You’ve selected great quotes. For readers interested in learning more about US-China relations, you can start by searching for the National Committee on US-China Relations page on the essentials (just Google it).