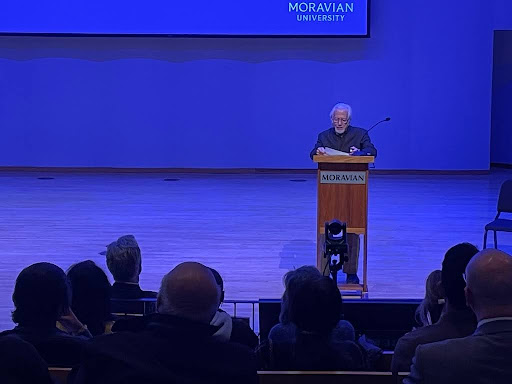

On Tuesday, April 15, Moravian University hosted its seventh annual Ravindranath Tagore lecture, an event that celebrates the life, philosophy, and lasting influence of one of India’s greatest literary figures. This year’s speaker, Martin Kämpchen, is a German scholar, translator, and author who has spent the last five decades in India. His lecture, titled “Lessons I Have Learned from Rabindranath Tagore,” offered students, faculty, and community members a personal reflection on how Tagore’s legacy continues to inspire deep thought and meaningful action.

Tagore was an Indian poet, philosopher, and polymath who lived from 1861 to 1941. In 1913, he was the first non-European to win a Nobel Prize in literature, particularly for the collection Gitanjali. The writer of both the national anthems for India and Bangladesh, Tagore is known for his broad artistic endeavors. Most of his works focused on beliefs in humanism, spirituality, nature, and anti-nationalism. Tagore founded Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, Bengal.

Born in Germany, Kämpchen first went to high school in Wisconsin and later studied German language and literature in Vienna and French in Paris. Over 50 years ago, he traveled to India to teach German. He received his second Ph.D. from Visva-Bharati, the university that Tagore started, where Kämpchen first encountered and fell in love with his work.

Kämpchen opened his lecture by tracing the intellectual and spiritual heritage that influenced Tagore’s thinking. He began with Sri Ramakrishna, who lived from 1836 to 1886, and, as a mystic, was a major figure in the revival of Hinduism. He was a known ascetic, practicing strict self-denial and a lifestyle of intensive simplicity. Much of his theory emphasized the unity of all religions and the importance of spiritual discipline.

Ramakrishna was a mentor for Swami Vivekananda, who further developed the philosophy with an emphasis on the importance of action and engagement with the world rather than withdrawal. Vivekananda promoted the idea that religion must address social problems and uplift the lives of the most vulnerable and that providing this support was the most effective way to serve god. He also started the Ramakrishna Mission, with which to carry on the work of his guru. It was at this ashram that Kämpchen first stayed with the monks.

Rabindranath Tagore incorporated these two previous philosophies—renunciation and empathetic work—into his own worldview while also adding what Kämpchen deemed the most important inclusion, poetry. Kämpchen defined this poetry as “a vision of life which enjoys beauty, enjoys nature, enjoys leisure, finds fulfillment in the arts—in literature and painting and, especially in music. This vision enjoys and finds emotional and spiritual fulfillment in activities that are, strictly speaking, not necessary, not profitable in a mercantile sense, which are not adding to our material wellbeing.” For Kämpchen, this final addition to the philosophies of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda made him feel as though he had arrived at the belief system he would model himself after.

Kämpchen recited a letter written by Tagore, which he felt exemplified this poetic adoration of the world. In it, Tagore recalls seeing a mother goat and her vulnerable young lying against her, both sitting in a sense of ultimate peace and comfort. This inspired within Tagore an ecstatic sense of love and wonder, which he defines as his “religious discourse.” Tagore viewed humans as living inextricably connected to nature, with this principle being one of his guiding lights in determining the choices he would make.

Tagore’s first lesson for Kämpchen was “to live within the unity of creation, to act in the world with a cosmic unitary consciousness always alive in one’s mind.” He prescribed this inner space as a tool for overcoming life’s difficulties and seeing our troubles at a greater distance.

The second lesson is “in order to protect the environment, we must refrain from acting from the ego, from greed, and instead to act from a wider consciousness.” Kämpchen argued that Tagore teaches that we need to consider the degradation of the environment in not just the terms of economic impact, but the damage it is doing to our emotional and psychic health. Supporting this argument, Kämpchen quoted two lines from one of Tagore’s famous poems: “My freedom lives in all the rites of the white sky/Liberated am I in every grain of dust, in every blade of grass.”

Kämpchen connected this lesson to the primarily American audience by referencing the works of the transcendentalist, Henry David Thoreau. He similarly viewed nature as a sort of heaven, which he lived among as he wrote his works. He also saw business as negative to the development of the human spirit.

Tagore’s final lesson for Kämpchen was “to make one’s own life experience relevant for the benefit of others. Rabindranath started a school and university in India. He believed in a holistic education.” It is from this that Kämpchen modeled his own school, also in Santiniketan, placing priority on the children’s ownership of their education and the value of learning and thinking for their own sake over that of careerism. He describes this method with an anecdote about a young student choosing to study a tree branch, which he sees as a natural privilege that should be afforded to children.

Kämpchen summarized his education from Tagore as: “I have learned from Rabindranath to be open to the experience of the world and to be actively involved in the progress of humanity, and, at the same time, to be totally open to the movements of the spirit and the will of god.” It is this balance—in education, in religion, in living—that Kämpchen professed to the campus as a path to a full life, following in the footsteps of Tagore.

The second lesson seemed to stick strongly in the minds of the Moravian student attendees.

John Cole ‘26 felt that he was reconsidering his connection to the environment as “a view from outside the self, a more collective view from space, as Earth has no boundaries, walls, or corners. Everything is connected.”

This was echoed by Cinderella Rivenburg ‘27: “What was important to me is how the priority of the economy and business on the environment is harmful to the soul.”