As a modernist writer and feminist, Virginia Woolf was in tune with the world around her, propelled by her extensive literary catalog. From the continuous industrialization to the aftermath of World War I, she refined her writer’s voice as a member of the Bloomsbury Group, a progressive collective of British visionaries and intellectuals. By the 1920s, she pioneered stream-of-consciousness writing, a literary style that reveals a character’s thoughts and feelings to interpret to the surrounding world.

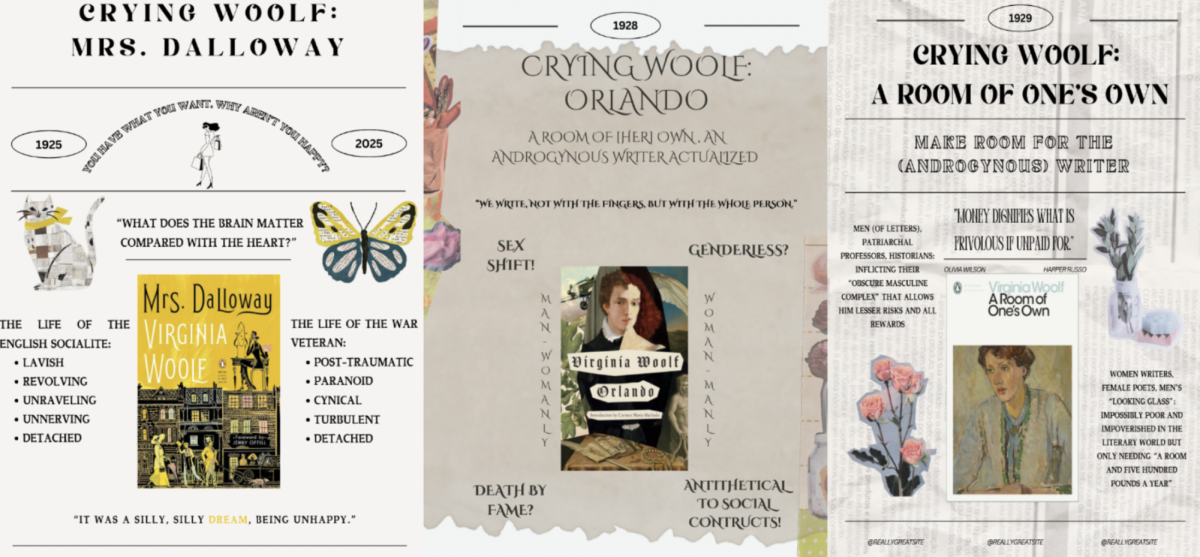

Her novels and essays display a mosaic of feminist theory, including A Room of One’s Own, blooming bisexuality in Orlando, and grieving the past in Mrs. Dalloway. What may not be easily detected within her works is a socioeconomic crux that lingers quietly: simply put, capitalism.

Woolf may not have openly declared capitalism as a culprit in novels and essays, but she alluded to its presence and when an aspiring writer or creator needs to play along as a means to an end. What does capitalism mean when you’re a woman, queer or have a mental illness? The Woolfian fashion of answering these questions is, of course, abstract. Unpacking her works provides context on what capitalism was like during her time and how we may see parallels to the modern day.

Mrs. Dalloway looks at the dual experiences of an affluent housewife, Clarissa Dalloway and a suffering war veteran, Septimus Warren Smith; these characters never meet, but the contrast between external conflicts of homelife and internal conflicts of post-war trauma respectively intermingles in a clear theme of not being able to move on from the past. Clarissa has a husband, a daughter, and a vast home, but is tethered to her string of lovers from the past, and a youthful life she will never get back.

Septimus, once an aspiring poet until he was drafted into war, is tethered to the deaths of his friends and the dissociation he experiences as a shell-shock survivor. Woolf engages with these characters through the portrayal of class distinctions and how they benefit from the system or not.

Clarissa benefits from the capitalist system without direct involvement as the wife of a member of Parliament, commodifying social status through parties. Her wealth belongs to her husband, and not her. Septimus, as a war veteran, is disregarded by the system, stratified by post-traumatic stress disorder, and unable to be financially well-off, the shadow of economic instability cast by World War I.

Woolf furthers the conversation in 1928’s Orlando, where upper-class upheaval meets androgyny, following the theatrical endeavors of a seemingly immortal nobleman from the 16th century. The titular character, Orlando, spends three hundred years yearning and writing against the disorientation of time until becoming a woman.

As scholar Reginald Abbott remarked, Woolf in this novel “celebrates true aristocratic consumption” through Orlando’s pursuits from love affairs to fixation on lavishness to fill a loveless void. Orlando is well-off but wants to become a poet (a common archetype among Woolf’s characters).

Woolf strikes the essence of a poet: financially vulnerable but forming social capital through writing. In the framework of regulatory capitalism, social capital and commodity may extend beyond “relations from the properties or characteristics of labour to a set of human relations … without regard to their class or status.”

Woolf also suggests poetry as socially transitional between the poet and the reader, asking, “Was not writing poetry a secret transaction, a voice answering a voice?”

As English Studies professor Mary C. Madden notes, Orlando “begins to iterate a theory of performativity relevant to gender (and class) identity which resembles that of the postmodern theorist Judith Butler.”

Orlando experiences an othering as a woman, spending most of the novel proving herself as a female poet, still retaining her noble status and publishing her Oak Tree poem.

A Room of One’s Own transitions wonderfully from the fantastical, near-satirical efforts in Orlando into the real-life feminist plights relevant to Woolf’s experiences. She paints “what-ifs” for female writers: if they could be taken seriously, if they could just be given a room of one’s own and 500 pounds to fund their literary aspirations. Even Woolf, advocating for this playing around with capitalism as a means to an end, is critical of what it symbolizes, warning, “Money dignifies what is frivolous if unpaid for.”

Outside of Woolf’s literary canon, her influences lie in contemporary movies such as Michael Cunningham’s 2002 book-turned-movie The Hours. The movie establishes interconnectedness between the three women of different periods: Virginia Woolf during a depressive period in 1923, Laura, a 1950s housewife enamored with reading Mrs. Dalloway to deal with postpartum depression, and Clarissa, a New York socialite in 2001, arranging a party to honor a dying friend. Capitalism overshadows the social roles of each of these women, hiding their fear and dissatisfaction with consumption as compensation.

Clarissa, for example, leads a privileged life, being able to indulge in the commodity of hosting a party. She must confront how someone such as her dying friend/ex-partner, Richard, struggling to live just above the poverty line as a bisexual man with AIDS, cannot indulge in the lavishness of a party meant for him. Richard remarks that Clarissa is “always hosting parties to cover the silence,” suggesting that even she cannot rely on private financial freedom to prevent her personal life from cracking any further, just as it was in Woolf’s 1925 novel.

For the modern writer, poet, artist, or creative, Woolf’s novels and the works inspired by her literary landscape shape how we know capitalistic rhetoric and what can be granted in self-interest, private property, or indulgence of material possessions.

Woolf did not intend to solve capitalism; she offered a workaround, tolerating it as a means to an end. This means using the system to propel what you need to survive – what a woman in 1920s England needs to find the agency that society does not fully allow, or what a woman, a queer person or a disabled/mentally ill person needs to sneak into a system that was not made for them.

Perhaps the Woolfian mindset of playing along with capitalism has its limits for those of us in contemporary society working minimum wage, or living paycheck to paycheck. But, there is still merit in saying that Virginia Woolf viewed capitalism as something to be heavily reworked, something that does not fit, and can be picked apart to see what could work to affect future change.