A worker at Moravian recently approached me and mentioned that he was going through a difficult time with the grieving process, and wondered if the newspaper would be interested in doing a story on grief.

Well, if there’s anything I know in this life, it’s grief. And it’s hard, but it’s also what makes life worth living. Anything good in life won’t last forever, and those horrible moments, even if they seem to have no purpose, are there to highlight all the highs you feel in life, as well.

Grief is something that everyone carries through life; it’s a universal sorrow, and there is no avoiding it, unless you never love in your entire life, but then what’s even the point of living? An amazing poem I read once changed my life, and it went like this:

“…that if you don’t have a memory / the past cannot devour you / when you stop moving for a brief / moment. Long enough to let the sorrow / catch the joy you never feel because you / don’t want to feel the sorrow / its companion. And if you don’t feel – / there will be nothing left to heal.”

This poem, by Diane Thiel, solved my entire life’s dilemma of wondering, “What’s it all for?” The sorrow expands your joy, and you need both to survive.

Grief is often framed through Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s well-known stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Those categories can be helpful, but modern psychology stresses that grief doesn’t unfold in a neat, orderly line. You might cycle through two stages in one day, skip another altogether, or feel acceptance in the morning only to plunge back into anger by night.

Newer models, such as the “dual process” theory, describe grief as a fluctuation: sometimes you’re fully immersed in the weight of your sorrow, and at other times, you’re restoration-oriented, trying to build new routines and focus on the future. Both sides matter, and both are part of healing.

And, an important thing to note, Kübler-Ross’s stages of grief were initially established for someone who was coping with the loss of themselves dying, not someone they love, so if you don’t fit into this mould of staged grief, that’s normal and actually more likely.

My father passed away five years ago this week, and I think of him every single day. Grief is a rollercoaster, not a passive feeling. It doesn’t pass through you ever; instead, I like the circle analogy. Grief is a large circle within the circle of your life; as your life grows around the grief, the grief doesn’t become a smaller circle. It still exists, it still hurts, and it’s still there, but you start to grow around it.

What helps in those moments isn’t always what we’re told in the cliché “time heals all wounds.” Tangible practices can carve out space for grief instead of suppressing it, such as journaling, creating rituals like lighting a candle or maintaining a small altar, or engaging in exercise to release pent-up energy.

Grief doesn’t cancel out joy; sometimes, laughter is the crack of light that lets us breathe again. For those who want support, there are resources here at Moravian: The Counseling Center, The Chaplain’s Office, and peer support groups led through The Counseling Center.

And grief in college hits differently. Balancing classes, jobs, and friendships while carrying invisible weight is exhausting. Deadlines don’t pause for heartbreak, and it’s easy to feel like you’re falling behind while the rest of campus keeps moving forward. That’s why it matters that Moravian, and any institution, make space for these conversations instead of burying them under productivity. Normalizing grief, rather than hiding it, lets students and faculty know they aren’t alone in carrying their losses.

And this, I can credit Moravian for. In high school, immediately following my father’s passing, some of my teachers did not give me any grace at all. A student who had previously maintained perfect grades suddenly started to struggle, and I wasn’t offered any support.

However, at Moravian, on my dad’s death anniversary, I’ve had teachers offer me the day off from class, pull me aside and tell me they were proud of me, and go above and beyond every expectation of a professor one could have, and for that, I am beyond thankful.

Grief is proof that you’ve loved, and proof that love has shaped you. When the weight feels unbearable, remember that the weight itself is a testament to the bond that mattered, and still matters. You don’t have to fit anyone’s timeline. You don’t even have to be okay every day. Healing isn’t about erasing the circle of grief; it’s about growing your life around it, slowly and imperfectly. Some days will hurt more than others, and that’s not failure, that’s love, still echoing.

You are not alone in this. And if you let it, grief can be more than sorrow; it can be the ground where grit, empathy, and compassion take root. You’ve seen how harsh the world can be; now be kind to others who may be fighting the same battle behind closed doors.

![The Downfall of Taylor Swift: AI, ‘The Life [and Demise] of a Showgirl’](https://comenian.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/unnamed-6-1.jpg)

Khristina Haddad • Sep 16, 2025 at 1:17 pm

Dear Liz,

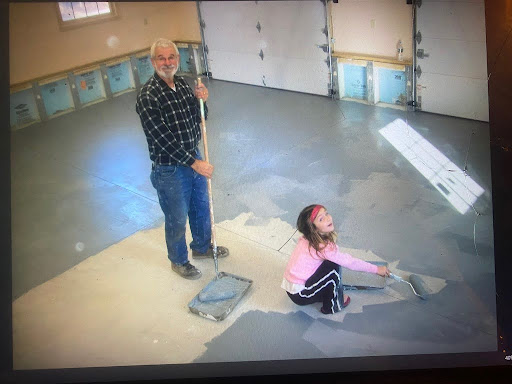

First of all, I am really glad you are back from Italy and on campus again. Secondly, you never cease to amaze me. What a humane article full of kindness and care for the human condition. I also love the photo of you and your father.

Sincere thanks and sympathy,

Khristina Haddad, political science