Julian Calv and “The Music of Moondog”

Throughout the last year and a half, senior music composition and education major Julian Calv has been researching and analyzing the work of American avant-garde composer Louis Thomas Hardin.

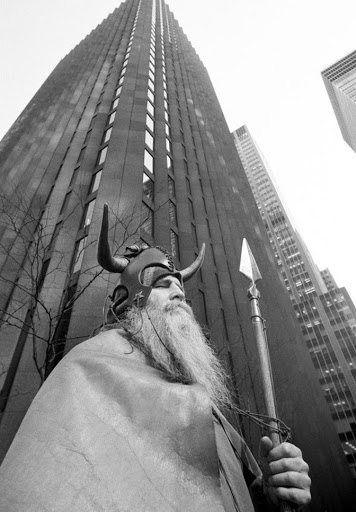

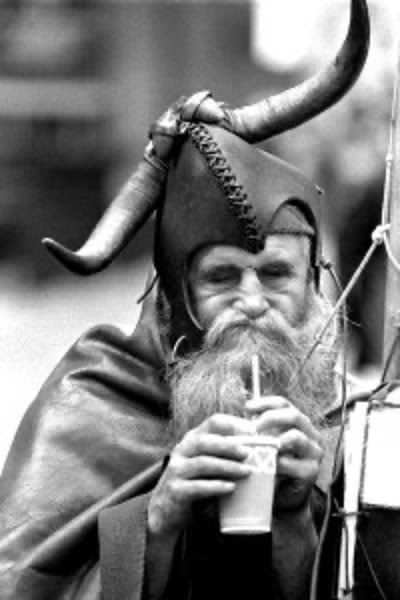

Hardin, most commonly known as Moondog, was a blind street musician and poet who performed on the streets of New York City dressed in Viking attire from the late 1940s until 1972.

Moondog could often be found on 6th Avenue, somewhere between 52nd and 55th Street, which garnered him the nickname of “The Viking of 6th Avenue.” At times, he would stand silently on the sidewalk in his Viking-style horned helmet and cloak, while other times he could be found busking or selling copies of his poetry.

Additionally, Moondog would go on to invent his own instruments, such as the trimba, which he would utilize in the creation of his music.

“I’d describe his music as neo-classical with a mix of minimalism,” Calv said. “Many fans of his music like to say he’s unclassifiable since his music throughout his life encompasses so much, but I think that’s the best way to summarize his type of music. Moon’s poetry is at times whimsical and other times reflective of his life, he loved to write couplets, he wrote over about 400 of them.”

For Calv, what began as a personal endeavor to learn more about the music of one of the most unique figures in American musical history quickly evolved into a formal independent study under Moravian professor of music and composition, Dr. Larry Lipkis.

Calv became fascinated with Hardin’s story and the music he created.

At the time, there were only two biographies written about Moondog: one by French speaker and producer Amaury Cornut, and another by Robert Scotto, a professor of English at Baruch College in New York City.

On October 21, 2020, Calv uploaded an Instagram video performing Moondog’s “Be a Hobo” and noticed that Cornut liked the post. At the time, Calv began analyzing some of Moondog’s music by ear and found some of his sheet music published online.

From there, Calv began emailing Cornut, asking him if anyone had ever done any musicology work with Moondog’s music, and what he thought about his work thus far.

Cornut replied, saying he didn’t actually read music, but he was able to put him into contact with Wolfgang Gnida, who operates the Moondog archives from his home in Germany.

Gnida, being the sole person with access to Moondog’s original braille manuscripts, is the last active transcriber of Moondog’s compositions who converts them to sheet music in modern musical notation.

All of Moondog’s music is written in braille, and any of his compositions written in musical notation during his lifetime was written down by others.

“He would hire writers to sit down with him and say, ‘quarter note, first space, beat two,’ and verbally communicate to them what to write on the paper,” said Calv.

Moondog’s main transcriber, Pam Gross would accompany him when he was at West 55th Street. Gross would then go on to formally publish his sheet music.

Calv expressed his interest in analyzing Moondog’s work to Gnida, who sent him a collection of four of Moondog’s rounds, each containing 25 songs.

“The actual transcribing from braille into sheet music is what [Gnida] does, but what I do is take the transcribed music and analyze it,” Calv said. “I talk about why the music was written this way and about the lyrics to the song. Through doing so, I was able to put together that some of the rounds are about very specific events in Moondog’s life.”

More than half of the music Moondog wrote during his lifetime has yet to be transcribed, and any recordings that are available make up less than twenty percent of the music he’s ever written. “Hundreds of songs by [Moondog] have never been recorded before,” Calv said.

Outside of the small range of his recorded songs, his music was mostly only heard during his live street performances.

When Calv mentioned his work, Lipkis suggested that he continue his research as an independent study to not only analyze Moondog’s work, but to see how his music could be used in an academic setting. Calv’s study is appropriately named “The Music of Moondog.”

The goal of Calv’s project was to analyze a series of Moondog’s rounds to understand more about their interpreted meaning, as well as what kind of techniques Moondog commonly used throughout the majority of his compositions.

By analyzing Moondog’s music, Calv was able to develop and present a unit of five lessons centered around how his music could be used in a general music classroom. Prior to beginning his formal research project, Calv also wrote a 13-page biography on Moondog’s life and journey as a composer.

The five lessons Calv developed, each of which is geared towards middle-school age students, teach the concept of musical canons and rounds, how to perform and understand rhythms in 5/4 and 7/4 time, as well as how to develop self-reflective thought at a middle-school level.

For their final lesson, the students write their own musical round collectively as a class which would then be performed at the end of the unit.

“I was able to teach this entire unit itself at a middle school during my pre-service teaching last semester, but it wasn’t how I really wanted to be,” Calv said. “It had to be adapted for online so nothing really went how it could have gone.”

For now, Calv’s independent study is completed, but he’s continuing to revise his work as he learns more about Moondog and his music.