The Real History of Thanksgiving

Photo courtesy of nytimes.com

The United States of America, now enveloped deeply within the capitalist system that made tradition a commodity, draws near to celebrating the holiday which is deemed “Thanksgiving.” It is a time for those engrossed in Anglo-American culture, particularly that of the northern East Coast by association, to feast upon homemade food.

Yet, in a post-colonial age the development of Thanksgiving is one which must also be scrutinized. As the atmosphere of the national holiday is subsumed by the pressures of Christmas, a reflection of the commercialism which spawned the day, must be examined with the same fervency as which the history of indigeous-English relations are deconstructed.

In the year 1621, the harvest of 53 pilgrims who had settled in the land across the

westward ocean was collected, representing survivors of the Mayflower Compact by the discernment of Pilgrimhall.com using William Bradford’s writings. So too was fowl, deer, and other laborious fruit gathered for a feast to honour survival and friendship according to Edward Winslow. It had been a harsh winter the previous year at Plymouth, Massachusetts, and the European colonists faced a failed, starved, expedition.

Supplementary aide given by the sachem (lord) Ousamequin, known also as Massoit, helped the freedom-seeking settlers through the brutal cold. The aspect often disregarded is the fact that the harsh winter affected the Wampanoag equally. The decision to help the English came at the expense of feeding their own community.

Another often ignored fact is that the Puritans were xenophobic in many regards, and fled not from religious intolerance but left because of their religious intolerance. The perfunctory negative discrimination that Puritans felt towards indigenous peoples was only stymied because of a base human need to survive. Whether the mutual benefits that governor John Carver saw with Ousamequin were out of the goodness of his heart, or merely the laying of a foundation to engage in trade, none may truly know, notes author David J. Silverman in “This Land Is Their Land.”

It is the deconstruction of the first Thanksgiving which has become the subject of decolonization. To truly understand the origins of modern Thanksgiving it is not the pilgrims and Puritans that must be looked to but the profiteers and politicians.

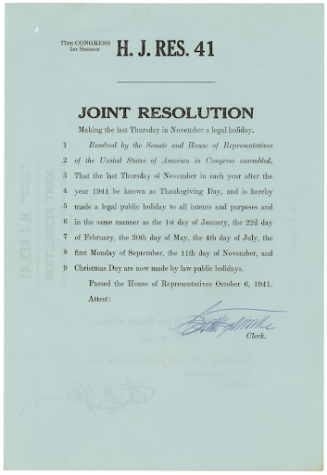

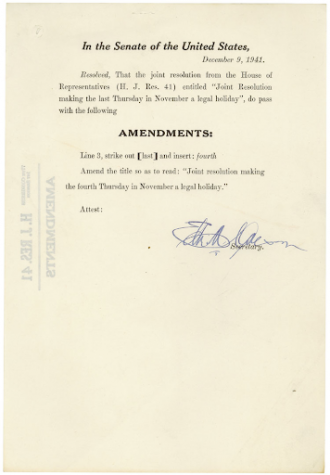

On Dec. 9, 1941, two days following the attack on Pearl Harbor and two before the United States formally entered World War II, Congress passed an amendment to the H.J. Res. 41 reading:

“Resolved. . . ”Joint Resolution making the last Thursday in November a legal holiday. . . .”

It was this resolution that ultimately made Thanksgiving a nationally recognized holiday. Generations preceding the original supper between the Wampanoag and the English Puritans were largely forgotten.

The feast was nothing of note as other colonies had and would experience similar circumstances all over North America. Little is known of the first feast from primary sources, save for one brief account by Edward Winslow, who described the event that lasted a little more than a week of gathering and merriment. The first giving of thanks passed into the annals and footnotes of history.

One hundred and sixty-eight years later, the first Federal Congress passed a resolution in which the president of the United States declared a day to give thanks in the nation: H.J. Res. 41. The passing of the resolution was but one action that the Founding Fathers and politicians of the post-Revolutionary War era took to formulate an American tradition key to building a sociological imagination loyal to the United States.

In 1863 Abraham Lincoln posited a solid date. Each president declared a day of giving thanks individually while in office with little consistency between serving terms. Thus it was decided that the last Thursday in November would be Thanksgiving.

So it would be until 1939 when president Franklin Delano Roosevelt, pressured by the Christmas spending season (an asset which stimulated the economy shifting towards war), issued a proclamation moving Thanksgiving to the second-to-last week of November.

Thirty-two states would follow suit, with 16 contending the declaration. In the confusion of the dual holiday, the notion of a Thanksgiving was an amorphous concept once more; a time to celebrate the bounties of the year as opposed to a single event marking a milestone of the calendar year. A resolution ratified on Oct. 6, 1941, shared Nov. 8th, and signed into existence on Dec. 26 that year would reunify the calendar date. The singular driving force behind the date conflict was another American tradition eagerly rising to prominence in the 1930s: consumerism.

In the aftermath of the second World War, the United States experienced an economic boom unlike any it had experienced before. Sensing an opportunity, two forces emerged to create the first Thanksgiving recognizable to modern American audiences. First to emerge was the explosive Christmas shopping season. Consumerism expanded significantly through a combination of stimuli and the Boomer generation basking in the luxury of their parents’ freedom to buy after years of rationing.

During this era, the corporate push for the shining Christmas intensified. Cashing in on an extended shopping season, companies pushed ever further into November, much to the detriment of the holiday.

Secondly, the newness of the 1950s onward prompted American households to explore the culinary limits within the kitchen. Domestic culture’s own growing obsession with splendor began a trend of massive, complex feasts cooked using every high-end technique with the latest in cookware technology. No longer was Thanksgiving an arduous yet simple affair.

As is true today, commercial farming provided middle class households with the resources to be able to glut themselves on food they did not produce the components of. Thus emerged the Thanksgiving of the modern United States.

“And although it be not always so plentiful, as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”

-Edward Winslow, 1621

With thanks to Dr. Jamie Paxton.