The Reasons Behind the Season

Photo courtesy: Jenny Nyström via Wikimediacommons.com

The cold grasp of Winter envelops all that which was once bountiful. The nipping of chill, the fangs of the biting frost – all that which was once green and fertile has withered in bitterness and contempt. In the words of Andy Williams: “It’s the most wonderful time of the year.”

The Christian Euro-American sphere of influence has begun to transition into that holiday which – above all others – dominates the year, whether it is liked or not. Yet beyond the ultra-capitalism that spans centuries, there is an ancient Germanic progenitor to the holiday which has evolved into many traditions celebrated today.

Stemming from the Germanic mid-Winter advent known as Jól, America’s Christmas finds much of its traditions within the pre-Christian north of Europe where portions of modern-day Germany, Poland, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden existed. During the Migration Period (roughly 100-500 C.E.) the Franks, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes, and Gothic tribes settled in the diminishing Western Roman Empire and spread Jól/Yule. To differing degrees, each of these tribes’ celebration of Jól existed, and the adoption of Christianity over a wide spread of territory changed the landscape of the mid-Winter. It is thus pertinent to recognize that most traditions which are identified as Germanic come largely from Scandinavia, Iceland, and England, where the admixture of Christian and pagan beliefs was yet discernable.

There is much about the holiday that historians, archaeologists, and modern pagans do not know about by virtue of time. Some traditions stand the test of time while others do not. Thus, there is no one Jól nor one interpretation or mid-Winter worship. Intercultural amalgams contribute much to the season and as information spreads in the age of information this fact only becomes more apparent. It is the celebration of life in the dreary Winter, which makes it the most wonderful time of the year.

From the elves who would sometimes give gifts to those who gave minor offerings of butter, bread, meat and drink, to the Christmas ham, much of what people typically associate with the holidays is rooted in pagan belief. Examples include Santa Claus, who himself is an amalgam of Germanic Yule Father and Turkish Saint Nicholas, as well as house spirits, who seek thanks for the good fortunes they bring.

An eternal symbol of Christmas, the felled pine which is brought into the home and decorated with garland, lights, and baubles has its origins within one of the many symbols of fertility in northern Europe. While other trees die it is the mighty conifer that defiantly lives evergreen. As the northward altar of the olden days, the Christmas tree is an item replete with decorum and offerings of juniper, pine, and rosemary fragrances.

So too is the Yule log, now confined to 24 hour broadcasts, a key feature of the individual holiday. From a single tree a large log would be set within the central fireplace. This log had to be big enough and with enough greenness (thus showing its virility) to burn continuously for 12 days. Within the modern age the tradition of the burning Yule log has continued through the burning of timber in the fireplace or candles throughout the home.

Similarly, an unending wreath decorated with mistletoe, a plant believed to hold immortality, had to last throughout the season to draw in vitality to a household. Other evergreens conferred unto those who bore them the strength of the plant which could then be spread unto others through gifts or a loving embrace. Without these loci of spiritual healing a family may put themselves in jeopardy during the season of death. Lively energies were especially appreciated during the 12 days and nights in which Yule was celebrated.

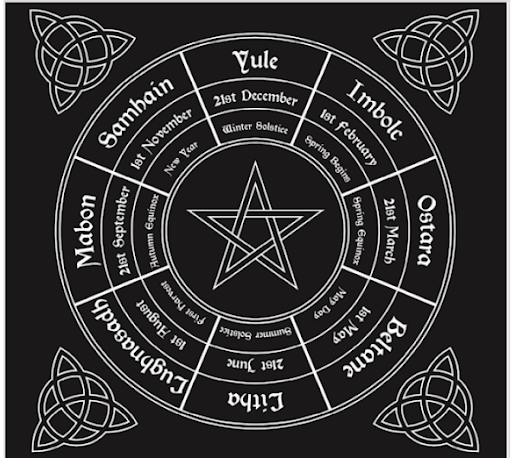

For 12 days Yule is celebrated typically beginning on the 21st of December, the Winter Solstice. Each day was marked by a particular celebratory deity or festivity with much feasting throughout. Unlike today, the days were celebrated in the aftermath of December 21st to mark the end of the Norse year. The origin of the shift from epilogue to prelude is the evolution of the Western calendar and the adoption of Christianity by Germanic peoples.

Evidence within the New Testament attributes the birth of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, sometime around the Spring or Summer. To make the celebration of Christ’s birth more enticing, the Roman Catholic Church saw the opportunity to incorporate the beliefs of its pagan neighbors into its traditions. Thus, as it had done with other holidays, notably that of the Roman Saturnalia, Mother Church adopted the symbolism of the old for the new.

Missionaries spread the word of Christ through this new Yuletide time throughout Scandinavia during the latter parts of the early Medieval period. Alongside tales of the Wild Hunt, a ghastly procession of the slain lead by Odin, Biblical passages were recounted. Legislative acts by lords such as King Håkon Den Gode (c.920-961 C.E.) cemented this new worship in stone. It is that foundation which would become the devotional time of giving in the high and late Middle Ages that would be reminisced by the English during the 19th century only to be commercialized as that century pressed forward into today’s Christmas.

Yule, however, still continues on with neo-pagan movements seeking to decolonize the imposed past pushed by imperialists and those of a xenophobic nature. Whether one follows the faith of old or of the new the spirit of the season has always remained even if its conjuration has changed from generation to generation.

To all readers, may Yuletide bring thee good fortune, light, and life with the new sun as we swear a sacred mead-oath or make a resolution this New Year’s Eve.