Meanwhile, in Ireland: Ostara

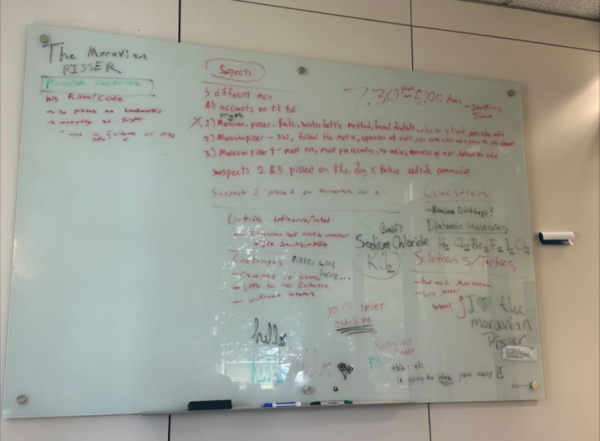

Photo courtesy of Zach Caflin

Ostara marks the Spring Equinox in Celtic tradition and was a festival adopted from Germanic tribes such as the Anglo Saxons, into the Celtic Wheel of the Year.

Unlike a number of other festivals that exist upon the Wheel of the Year, the festival of Ostara is relatively modern. It first begins to show up as an organized festival around the 8th century CE in records by St. Bede, who wrote about the connection of the goddess for whom it was named, the goddess Eostre (Pronounced Oh+Struh).

Historians believe that it is from her name that the name Easter is derived. Like many Christian religious traditions, much of what is done to celebrate Easter comes from older pagan practices, a common way to explain Christian ideals to the people. It is also not necessarily Irish in origin, unlike a majority of other festivals that exist on the modern Wheel of the Year, though it indeed is Celtic and influenced by the aforementioned Germanic traditions of the later Anglo Saxons who settled alongside the Celtic Britons.

According to the legends, Eostre, goddess of spring, was said to have found a poor songbird frozen solid while she was out for a walk one day in mid spring, around the equinox. Being skilled in the art of transfiguration and feeling sympathy for the wee creature, she was able to revive the songbird by turning it into a hare, but it became a unique half breed of sorts.

This hare could continue to lay eggs like the bird it once was! Thus, this became a symbol of restoration, renewal, and new life. It is also believed in some folklore that at dawn every day, the hare dies and with it the moon, only for them to be resurrected once more as the twilight overtakes the world, bringing the night. This ongoing cycle is said to make the hare a symbol of immortality, fertility, and the aforementioned restoration, renewal, and new life. Likewise, the moon shares these symbols.

This stands in a rather curious contrast to the beliefs in Ireland, where the sun, and the goddess Bríd (Pronounced like Breed, anglicized as Brigid) who was said to bring the sun back at the start of every spring, was what indicated renewal, life, and the ongoing cycle of eternity.

In Ireland, the festival of Imbolc, which is associated with both the earlier goddess Bríd, and the Saint who was named for the goddess, Saint Brigid of Kildare, was considered among the sacred Fire Festivals, the four key points of the year in which the seasons turn on.

These Fire festivals, which include Imbolc (Pronounced Ihm+Bolk) on February 2, which marks the beginning of spring and the planting period, Beltane, or Bealtaine (Pronounced Ball+Tawn+yuh) in Irish, on May 1, which marks the start of the growing period of summer, Lughnasadh (Pronounced Look+Naws+uh) on August 1, which marks the start of the autumn and the harvest, and Samhain (Pronounced Saw+in) on October 31, which marks the end of the harvest, the arrival of darkness, and is considered the point of the new year.

Ostara itself, when looking at the modern Wheel of the Year as a whole, falls in the heart of the spring, with Imbolc before it marking the start of the spring, and Beltane after it marking the end of spring.

The symbols of the egg in connection to Easter began with the tale of Eostre, but in later Christian beliefs, it became associated with the Holy Trinity, a way to explain the concept of a “Three in One” figure, not dissimilar to the Celtic concept of a triple goddess, such as the aforementioned Bríd. Similarly, Saint Patrick, Naomh Pádraig (Pronounced Neev Paw+Drig) in Irish, made a point of integrating pagan beliefs into Christian teachings, and it is thought that his mission work is what may have brought the festival of Ostara, along with Easter, to Ireland, as he taught.

One such thing of this nature worth noting is the Celtic cross, a cross featuring a circle around the branches. This circle represents the sun, which as mentioned, was of great importance in the Irish tradition when regarding spring. It is believed that he did this in order to help the converting Irish pagans associate the symbol of the cross with divinity and resurrection, further associating the festival of Ostara with the Christian celebration of Easter.

Other symbols include the moon, which, in addition to what was mentioned above, also represents various goddesses across different Celtic traditions. Flowers such as lilies, crocuses, daffodils, pussywillow, primrose, and really any mid spring flower or flowering tree are also strongly associated with the festival, a symbol of returning life.

Likewise, the festival of Ostara became a time to recognize mothers and children, and was considered the height of fertility, among people, animals, and plants, and was the prime part of the year for planting, as such.

Colors such as green, yellow, white, and purple are colors all associated with the festival. Green represents life, yellow and white for the sun and fire, with white also representing the goddess Eostre herself, and purple for fertility and prosperity.

Finally, dawn birds, such as larks, blackbirds, and European robins, are also associated with Ostara because of their association with daybreak, and thus act as a contrast to the hare, symbolizing the return of the sun and of warmth as the winter officially ends and the summer makes its return once more; an eternal cycle and duality that goes on, of the sun and moon, light and darkness and life and death.

Dara Desmond • Apr 2, 2025 at 3:46 am

And ‘Bealtaine’ is pronounced more like (B’yow-ta-na) in the south. The pronunciations you are using seem to be to be northern Irish

Martha • Mar 17, 2023 at 1:17 pm

The festival in this article of ‘Lughnasadh’ is actually spelled ‘Lúnasa’.

Martha • Mar 17, 2023 at 1:19 pm

As well, instead of being pronounced (look-naw-sa), it is pronounced (Loo-na-sa). Pronunciation can differ though in different regions.