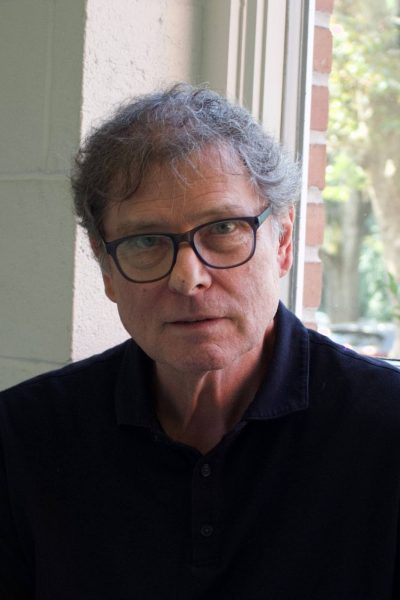

Professor Spotlight: Dr. Jane Berger

Photo courtesy of moravian.edu

Dr. Jane Berger is an associate professor of history at Moravian University. She studied chemistry and English at the University of Delaware, earned her master’s degree in deaf education at Gallaudet University and a second master’s in history from the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She received her Ph.D in history from Ohio State University. Recently, Berger won the 2022 David Montgomery Award from the Organization of American Historians for her book “A New Working Class: The Legacies of Public-Sector Employment in the Civil Rights Movement.”

What inspired you to go into your field of study?

Before I became a history professor, my first job for a long time was an American Sign Language English Interpreter. I interpreted in higher education, so I liked being in college classrooms. And then I had a chance to go with a group of deaf people to Cameroon in Central Africa. It was a really, really wonderful and enriching experience, but I also saw poverty up-close in a way that I had not known poverty before. It also reminded me, as someone who grew up in Baltimore, of the wealth disparities that we have in this country. And I wanted to try to figure out why the world still has so many problems. You’d think we’d have made a bit more progress by now, so I decided history would be a good discipline to go into because I could try to figure out how we got to where we are now. I went into it not really expecting to even get a Ph.D. I went into a master’s program, and most of it was to try to figure out why the world is so screwed up.

What projects are you currently working on?

Two things, actually. When I was in graduate school getting my masters, I studied African History as one of my fields, and then later when I was getting my Ph.D, I kind of expanded that and did International Women’s History. So one of the things I’m really interested in and have been working on is comparing the experiences of Black women in the United States and their depictions and stereotypes with the stereotypes that have been used to describe women of color in the global south. The thing that really strikes me is that the stereotypes are sometimes the exact opposite. Women in the global south are sometimes elevated as the victims of transnational and global economic change in a way that denies them any agency, and women of color in the United States are often depicted as overly dependent on government benefits in a way that inaccurately identifies who benefits the most from government spending. So I just think it’s interesting how they’re opposites and how the stereotypes emerged at the same time. And then the other thing I’m working on is a chapter about a labor leader – a Black man who was a leader in The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). I talk about him in my book that just came out, and because of that I was invited to participate in a book project where everybody’s running a different chapter about a different aspect of his life and political activism. So I get to do that, which is really exciting to me for the main reason that I’m going to get to meet him.

What do you think is the most recent important development in your field of study?

It isn’t like medicine, where there’s a study that cured a disease, but I think where recently a lot of people have looked to history is in helping us explain the election of Donald Trump and the rising popularity of leaders in the world who we might call populous authoritarian types. We can look at U.S. history and see the roles that factors, like changing economic context, race relations, and dog whistle politics, have played. Historians in many fields were saying, “We could help explain this!” as we saw the unexpected rise of that kind of politics.

What job would you have if you couldn’t be a professor, regardless of salary and job outcome? Why?

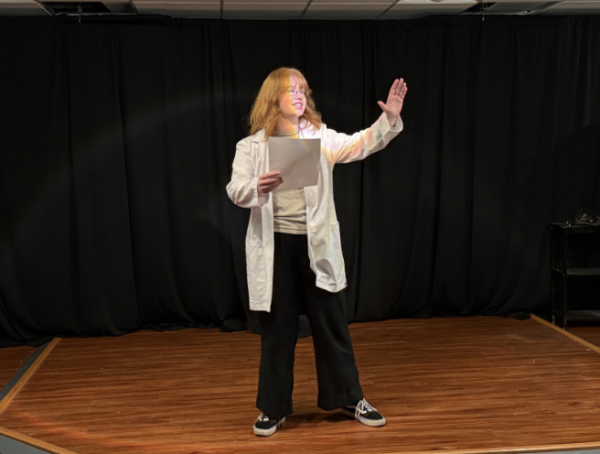

I really liked being an interpreter. The reason I stopped being an interpreter is eventually I did get tired of telling people what other people were saying – I wanted to say something myself. I would say I’d enjoy conflict resolution. I’m on the Bias Response and Intervention Team, and one of the things that I’ve really been learning about and enjoying is helping to facilitate difficult conversations. Also, if I was a scientist, I’d want to be a meteorologist, because I think weather is really cool.

What do you know now that you wished you knew when you were in college?

I was not a first-generation student, but my father didn’t graduate from college and my mother got her bachelor’s degree when I was a kid, so they didn’t necessarily have a lot of information about college. It makes me have some things in common with first generation students; for example, I thought you had to pick something from high school to major in for college, and so I picked chemistry. I think I was very cautious because I didn’t know I had as many choices as I did. I wish I had known that some of the things I had a passion for were things I could actually study, instead of thinking I had to pick something like chemistry, which I did not have a passion for and wasn’t good at. I wish I had known how many opportunities there were because I think I limited myself.

What is your biggest student pet peeve?

Something that bothers me is when students are on their phones during class and not paying attention. I understand it – sometimes I’ll go to meetings and you’ll see me with my phone – but I wish students would just say, “Ok, I have to be in this class for 70 minutes, and I’m going to really jump in and engage.”

What should students expect from your classes? What is the secret to succeeding in your classes?

I would say engaging the ideas is the most important thing. Even in my 100-level classes, we’re always talking about ideas and trying to make sense of the past, why things happened, and what people’s motivations were for doing what they did. So I think a good idea will get you very far in my classes.

What was the last streaming show that you binge-watched or the last good book that you read?

I am currently reading “The Crooked Kingdom” by Leigh Bardugo because it was recommended to me by my 14-year-old. It’s good – it’s the second one in the series – “Six of Crows.” I already read the first one. It’s about these young people who live among people who steal and gamble, and they come from different places and have different powers. One of them is really good at shimmying places and not being seen, and another one is a warrior-type, and another is able to infiltrate people’s bodies and make them feel certain ways. I never usually like these kinds of fantasy books but it’s really good! It’s entertaining and the characters are likable.

What is something interesting about you that most people don’t know?

Something I get a kick out of is that I interpreted for Barack Obama while he was running for president. I have a picture of that in my office in Comenius Hall, and I think that’s so cool.

Can you talk a little about the writing process of “A New Working Class?” What were the most challenging and/or fulfilling aspects of creating it?

Well, writing is hard. I think the hardest thing for me was gaining control of my writing. Instead of being driven by the facts that I gathered or the quotes that I had, I needed to be in charge of what I was trying to say so that the paragraphs made a point and made sense as you went through them. Because sometimes – and this is why I can be really empathetic with students who write papers for my classes – you have this information like historical data and just think, “Ok, let me dump this in.” And it’s really hard to get to a place where you can control it and say what you want to say. I also wanted it to be interesting, even though it’s a history book and mostly only historians are going to read it, so I asked a student who was a really excellent creative writer to be my research assistant. She actually read the whole thing and really helped me bring it to life, like invoking the senses to help people imagine scenes.