Meanwhile, in Ireland: The Druids, Not What People Think

Photo courtesy of Zach Caflin

When one hears the term druid, a distinctive image of an old man with a long white beard, clad in a white robe, likely talking to trees and worshiping things like the mighty pond scum is probably the first thing that comes to mind, or some variant of this.

But in truth, who the druids were in ancient Ireland, is a very different reality to this. Druids existed across many eventually Celtic regions; however, due to regional isolation, the druids in Ireland were much different than elsewhere.

They were scientists, doctors, made up the legal system, were historians, acted as cultural and political ambassadors, were protectors of the arts, preserved the religious traditions, and were definitely not exclusive to just men. Anyone who was willing to go through the years of rigorous education could become one.

And while the druidic ways largely died when Christianity came to Ireland, in other ways it lived on through blended traditions that have led to a unique culture developing and surviving, even despite what would have seemed to be impossible odds.

To become a druid was no easy task. A prospective druid would spend years being educated in a variety of subjects, in some cases even spending upwards of twenty years being educated before becoming a fully-fledged druid. In society, a fully-fledged druid was among the highest members, and often were ranked among the kings and queens.

Different jobs existed for those among the druidic orders, and much of society was run by them in one regard or another. Perhaps the most important of these occupations of the druids were the Brehons, the folks responsible for the legal system.

The system of laws in Ireland until the end of the Gaelic Irish period, which lasted until the Flight of the Earls in 1607, were known as the Irish Brehon Laws, and were created by their name sake. These laws sought to keep equality between the people, such as the marriage laws. In short, there were various levels of marriage all depending on the situations of the individuals entering the union, and each level was designed to effectively equal the field for them.

Additionally, there was a one year trial period built into every marriage, in which either party could break off the union without having to go through a formal divorce court. Unlike many other places in Europe, ancient and Gaelic Ireland was comparatively a far more equal and inclusive place to live, thanks to the Brehons.

Additionally, the Druidic orders were not limited to men only. While it is true that there were more male druids than female, women were not excluded, and they did not have to be married to a male druid to become one themselves either.

Among the female druids of note, there was Geal Chossach (Pronounced Gall Koh+Suh), “White Legged,” of Inisoven, Donegal, whose grave there can still be visited. Then there was Milucradh (Pronounced Mill+OO+Kruh) “Hag of the Waters,” who was said to have cursed the king, Fionn, into an old man with water from Lough Sliabh Gullin (Pronounced Low Shlee Goo+Lin). According to some traditions, Milucradh still wanders Ireland to this day, very much alive, despite being thousands of years old. And then there were the famous sorceresses Eithne (Pronounced En+Yuh) and Ban Draoi (Pronounced Bawn Djree), noted for their magical abilities and connections to nature and the Otherworld.

As Ireland began to transition between the ancient pagan practices and the new Christian practices, various curious things also began to emerge. In regards to the women, for a while there was a lack of clear distinction between druidesses and nuns. The word for nun was actually the same word used for druidesses, Cailtach (Pronounced Kall+Tock or Kall+Taw), and the interweaving of the old traditions and new practices saw an interesting integration of the two together.

Most notable would be Saint Brigid of Kildare, or Naomh Bríd (Pronounced Neev Breed) in Irish. Besides Brigid herself often being suggested as having been a Christianized version of the Goddess with whom she shares a name, other suggestions have her as a high priestess of a druidic order of women who focused on the worship of the Goddess Bríd. The most curious part of this is the fact that Brigid’s original Abbey at Kildare was built on a site noted as being the holy site for this druidic order of women, known as the Daughters of Fire. The followers of Brigid of Kildare are among a number of Christian nun groups who are considered to have been in one regard or another, druidesses.

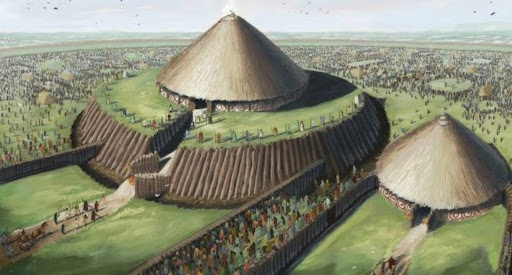

One of the most lasting legacies of the druids are the ancient cultural centers they were instrumental in establishing. In the ancient days, there were five kingdoms, each with its own cultural hub, and the seat of the High King as a sixth.

These were Rathcroghan (Pronounced Rath+Krow+Kuhn), Emain Macha (Pronounced Eh+Mayn Maw+Kuh), Uisneach (Pronounced EE+Shnaw), Cashel (Pronounced Kaw+Shell), Dún Ailinne (Pronounced Doon Eye+Lee+Nyuh), and Tara. The Rathcroghan, the capital of the Western kingdom of Connacht (Pronounced Koh+Nawt), was notably the seat of the ruler of Connacht, most famously being the famed warrior Queen, Queen Medb (Pronounced Meave).

Notably, a group of druids were the reason for why Medb became Queen, having prophesied that she would rule and no man would become King of Connacht unless they were married to her, guaranteeing her total control over the Western Kingdom. Similarly, her druids would continue to give her prophecies that would shape Iron Age Ireland and the complex political systems that existed then.

Among the other notable things connected to the Rathcroghan, it was there that the festival of Samhain (Pronounced Saw+in) was said to have originated, and among its 240 sites that make up the complex, is a cave known by the name Uaimh na gCat (Pronounced Oo+Way+nuh Got), the Cave of Cats.

This cave is where the festival began, as it was considered by the people as a portal to the Otherworld, or the various realms of the supernatural races, specifically to the domain of The Morrígan (Pronounced More+EE+Gun), the Goddess of War, Death and Fate.

According to at least some of the traditions, it was said that, in revenge of The Morrígan against the humans pushing the Tuatha de Danann (Pronounced Too+Ah+Uh Day Dawn+Uhn) underground was what prompted many of the traditions of Samhain that would still be practiced in modern Halloween celebrations.

Tara, or most notably the Brú na mBoinne (Pronounced Broo Naw Boy+Nyuh) complex, is another location key to understanding the druids. The Hill of Tara itself was the seat of the High Kings of Ireland, and nearby stood the Brú na mBoinne complex, the sacred burial place for these great rulers and others of status.

Like the Rathcroghan in the west, Tara and Brú na mBoinne were thought to exist atop a portal to the Otherworld. The most notable structure within this complex is the Newgrange, a massive passage tomb dating to 3,200 BCE, predating both Stonehenge and the Pyramids of Giza. This ancient structure was constructed in such a precise way so that the inner chamber would only flood completely with sunlight at dawn on the Winter Solstice.

Pre-Celtic practices in Ireland, such as with both Brú na mBoinne in the East and the Rathcroghan in the West, developed uniquely from other regions that would eventually become “Celtic,” and as such, resulted in the uniquely Irish practices of the druids there, upon the establishment of the druidic orders. And to this day, the Newgrange remains a popular gathering point to welcome the sun back into the world as the Winter Solstice marks the turning point of the year.

(The Newgrange, from the Meath County Council)

Curiously, unlike other mythologies at the time, Irish traditions were terrestrial in nature, whereas many others, such as the Greeks and later Romans. The concept of druids as tree huggers likely stems from the idea of the sacred trees. According to folklore, various trees hold spirits, such as the Oak tree, Doire (Pronounced Dweer+uh) in Irish, or Anglicized as Derry.

The Oak was considered among the most sacred of trees for the reason of the god of light and healing named Bíle (Pronounced Bee+Luh). Bíle took the form of a great Oak, and it was through him that the great Mother Goddess Danu (Pronounced Daw+New) bore her son Dagda (Pronounced Dock+Duh), the “Allgod.”

In ancient days, Ireland had no written language, but everything was recorded through oral traditions. Storytelling became an instrumental part of the functioning of society and it was the druids who were the keepers of these traditions.

This was the case until the 4th century CE at the earliest, when a written script known as Ógham (Pronounced Ock+Uhm), named for the Irish God of wisdom and poetry, Ógma (Pronounced Ock+Muh), was introduced. Each Ógham symbol was named for the sacred trees, and it was these Ógham symbols that would lead to the development of an Irish “Zodiac,” integrating a system that dates back approximately to 1000 BCE with the newly invented Ógham Script. Like the supernatural beings who existed in folklore, the Irish “Zodiac” was far different to others like the Greeks and Romans, once more being more connected to the earth than the stars.

Among the things within the Irish “Zodiac,” the sacred trees and their accompanying Ógham letters were and are the most important. And even after the introduction of a written language, the art of storytelling remained an instrumental part of Irish culture and identity, even to this day, a part of the lasting legacy of the druids.