Meanwhile, in Ireland: Misconceptions of the Faerie Folk

Artist depiction of The Morrígan by Sabrina Moody

When one hears the name Leprechaun, the common image conjured is likely something in the same vein as Lucky, the Lucky Charms Leprechaun – charming, upbeat, red haired and clad in green. Similarly, one would probably imagine some terrifying spectre, a demonic ghost whose screams cause the deaths of those who hear them when one says to imagine a Banshee.

Yet these depictions, as well as of many others of the Faerie Folk, are simply not the true depictions of them at all, but rather twisted by Americanization and Anglicization. To understand these creatures, one must first examine the traditional Irish view of the world, nature, and especially of death.

In pre-Anglo Gaelic Irish culture, death, to put it simply, was not viewed negatively, in contrast to the common western view. The Celtic view of death was one reason the Romans reported as to why conquering them was more of a challenge than most everywhere else, as the people were reportedly unafraid of death. Reports to Alexander the Great even earlier than that had similar comments regarding the people of Ireland particularly. And even in modern Irish culture, aspects of this continue, as evident by the way most Irish wakes go down. As the old saying says, the only difference between an Irish wedding and an Irish wake is that there is one less drunk person at the wake.

While of course this does uphold a negative stereotype about Irish folks being rowdy, unruly, and drunk, it also does hold some truth about the Irish view of death, primarily that one should not mourn the death but celebrate the life.

In the old days, it was widely viewed as a transcention into the parallel Otherworld, rather than to a Heaven or Hell. This Otherworld had many different domains, such as that of The Morrígan (Pronounced More+Ee+Gun), which was thought to be accessible through Uaimh na gCat (Pronounced Oo+Way+nuh Got), near the Rathcroghan (Pronounced Rath+Krow+Kuhn) in modern day County Roscommon, or the famed Tír na nÓg (Pronounced Teer Naw Nawg), which translates to The Land of Eternal Youth. But unlike most cultures, especially other Western cultures, there was not a distinctive “Heaven” or “Hell”. From a Western perspective, the Tír na nÓg often gets paralleled with Heaven, and the domain of The Morrígan with Hell, but in reality they were not meant to be like either.

This then leads into the views of various Aoí Sídhe (Pronounced EE+Shee), also called the Daoine Sídhe (pronounced Dee+Nuh Shee), Faerie Folk.

To begin, Banshee folk, or Bean Sídhe (Pronounced Bawn Shee) in Irish, which translates roughly to Woman Spirit or Woman Faerie, Bean meaning woman and Sídhe meaning spirit or Faerie, was not considered, mainly, as a negative entity. Rather, they were creatures taught by The Morrígan herself, who is the Irish goddess of War, Death, and Fate, to predict the deaths of the members of five specific clans (O’Neill, O’Brien, O’Connor, O’Grady, and Kavanagh, who are actually the only five clans who could hear a Banshee) and keen for them.

Keening itself is a practice, in tradition, of women singing a song without lyrics, something known as “mouth music,” that was meant to, in many regards, mimic the song of the Banshee, a lament in remembrance of those passing to the next life. And oftentimes this practice was looked down upon by those of the Anglos and Anglo-Americans who witnessed it happening as more and more Irish immigrants came to places such as the United States in the 19th century.

Such was the case with George Templeton Strong. Templeton Strong was among these Anglo-Americans who were very anti-Irish, and keening was a topic he often wrote about and looked down upon. In one instance in particular, he witnessed a group of women keening for the loss of several Irishmen who tragically died during a construction accident and then proceeded to comment how strange it was and how culturally removed the Irish were from the Anglo-Americans, likening them to the Chinese, who were also facing similar discrimination at the time. Templeton Strong was hardly alone in these views either, but was simply one of the noisier commenters on the Irish.

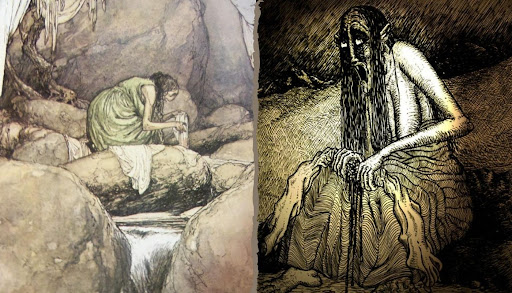

Similar to depictions of The Morrígan in various folktales, a Banshee could take different forms, from that of a Raven, Rook, Magpie, or Crow, to a maiden, to the more commonly imagined old crone. Most times, at least according to the old stories, even reported the rare occasion a Banshee was seen, and she was in the form of the old woman, with silvery white hair, by the side of a river or stream, washing the bloody clothes of the person about to die and crying for them.

The crying associated with the Banshee was not what brought about the death, but simply was because they knew the death was inevitable. In many regards, the Banshee was hardly the demonic spectre depicted in Anglicized media.

There is, however, the Scottish cousin of a Banshee known as the Bean Nighe (Pronounced Bawn n+EYE+Uh), who indeed is considered a negative being. Unlike her Irish counterpart, the Bean Nighe is said to be the spirit of a woman who tragically died in childbirth, after which she is cursed to remain trapped here, forever washing clothes, and not pass to the Otherworld until the day on which they would have normally died if their lives were not cut short. They are forced to wash the clothes of those about to die, particularly those who are to die a violent or sudden death, though even they have a positive side, for if one approaches a Bean Nighe with caution, they may be granted a wish or knowledge.

Curiously, a Bean Nighe may be avoided regarding her creation as a lurking spirit if all the clothing belonging to said woman who passed in childbirth is washed immediately. The Bean Nighe, being a trapped human spirit, is seen far more negatively, less because of what she does, and more so because of the tragedy of her soul being unable to transcend.

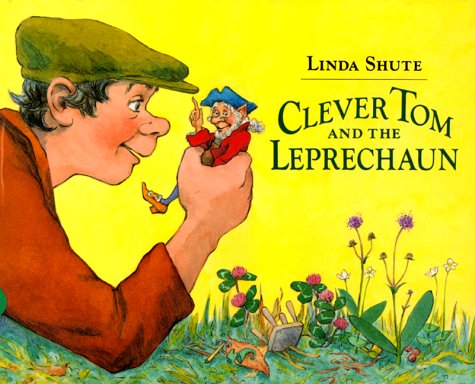

Similarly, the Leprechaun, whose name comes from the Irish leipreachán (Pronounced Lay+Praw+Kun) and lucharachán (Pronounced Loo+Kar+aw+Kun) meaning “Small Body,” or Leath Brogan (Pronounced Lay Bro+gun) meaning “Shoemaker,” is entirely misconstrued as far from what they are in most Irish traditions. In contrast to the Banshee, the Leprechaun was actually seen as a negative creature, or at least one who was mischievous and even malicious toward humans. Their appearance, no thanks to our dear Lucky, is also very commonly misrepresented in, especially, American media.

Traditionally, a Leprechaun would be a wee fellow of no more than a foot or two in height, but rather than the green clad, red-haired fellow, he would be an elderly lad with white hair, clad not in green but in a red coat, blue waistcoat, yellow or brown knickers, blue or white stockings, and yellow or brown buckle shoes with a leather, sometimes blue, tricorn cap he would wear.

Likewise, he was the cobbler for the faerie folk, a solitary being in most regards who often took pleasure in messing with humans, whether as harmlessly as tricking them, or in some cases even becoming violent. This depiction is accurately shown in the artwork for Linda Shute’s telling of The Field of Boliauns, Clever Tom and the Leprechaun, both in physical depiction and in the depiction of a Leprechaun as a mischievous being who enjoyed enciting mental torture upon a human. Of course, it is true that Leprechauns tended to be greedy and hoard riches, but for the most part, they were simply solitary beings who spent their days hidden in the hills, cobbling shoes.

Another Faerie creature who has fallen under this misconstruction of what they are is the Selkie.

While not as far removed from the way they are traditionally depicted, fantasy roleplaying games have still managed to take a grasp on them and create an image of them far from what they are meant to be. Games such as Dungeons and Dragons have seemed to invent a bastardized version of the Selkie, some odd half-breed like a mermaid where the legs are replaced by the lower half of a seal, and the upper half appears relatively human. Similarly, they tend to have reserved or even sometimes nasty personalities, but all of this, like the Banshee and Leprechaun, is far from the way they are in Irish folk tradition.

The actual Irish Selkie, for starters, is never a half form. He or she is either entirely in a human form or entirely in a seal form, and these forms are in such a way that one would not be able to tell them apart from a regular human or regular seal. One changes between forms by shedding their sealskin or donning it once again, but never would they be in a half form. In personality, they were often very outgoing and this often would be the cause of their sealskins being stolen.

Female Selkies in human form tended to also be the more outgoing ones, and thus more stories of female Selkies exist. In general, Selkie folk are among the few Irish faeries who don’t actively seek revenge on the humans for pushing the Faeries underground. Also, a Selkie in human form almost exclusively has dark hair, dark or sometimes blue eyes, and fair skin, which is actually fairly unique for the Faerie Folk in Irish folklore, as golden hair was considered representative of sovereignty, and red hair of supernatural ability, thus meaning most Faeries had one of the two.

This is interesting to note because of the Selkie’s connection to this world, which they were considered to maintain even after the other Faerie Folk had been pushed underground into the Otherworld by the humans. One could make the connection easily between the view of dark hair in connection to the Earth, and the Selkie’s remain in this domain rather than in the Other, though this is more of a curious thought.

What does fall closer to the classic Mermaid, in Irish folklore, is a cousin of the Selkie known as a Merrow.

Merrows are the, primarily, southern cousin of the Selkie, usually with the golden hair and blue eyes of the Faeries, fair skin, and fins like a classic Mermaid. Some, it should be noted, are described with green hair, black eyes, and green tinted skin, a regional difference. And in contrast to the Selkies, male merrows often look far less human and far more like a monster. However, in general, they behave much like the Selkie in terms of how they can come to land, but rather than shedding their skins, a Merrow would, typically, have a magical cap, usually red and adorned with feathers, that allowed them to take human form.

The cap worked in the same way as the sealskin of the Selkie, meaning that if the Merrow were to have it taken, they would remain trapped on land until they either perished seven or so years later, or were able to retrieve their caps and return to the sea. And like the Selkie, if they did retrieve their caps and return to the sea, they would not be able to take human form again.

In general, when one hears the term Faerie, one would often imagine the sort of winged pixie like Tinkerbell, but they are anything but. In Irish tradition, the Aoí Sídhe, the Faerie Folk, range from the gods such as The Morrígan, to supernatural creatures such as the aforementioned. And what each being and creature among the Sídhe folk are, are often quite different to how they have become depicted in Anglicized media. Irish folklore, to be properly understood and appreciated, cannot and should not be viewed through the Western, Anglicized lens.

Dr. S • Apr 29, 2022 at 2:30 pm

great writing! excellent article