Weathering War: An Interview with Writer Matt Gallagher

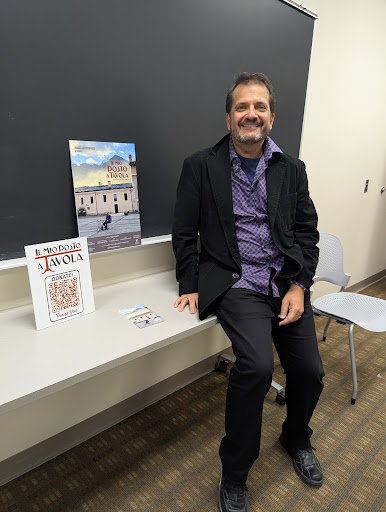

Matt Gallagher is a prolific writer whose literary oeuvre, which includes the novels “Youngblood” and “Empire City,” focuses on war. He is a graduate of Wake Forest and Columbia and currently works remotely as an instructor for New York University’s English Department’s Words After War, a workshop program that brings together veterans and civilians to study conflict literature. Gallagher’s focus on war extends to his work in March 2022 to help train a civilian defense force in Lviv, Ukraine, which was featured on CNN’s Anderson Cooper 360°.

At 7:00 pm on Friday, March 17th, in Prosser Hall, Gallagher will give the keynote address at Moravian’s 2023 Writers’ Conference. His talk, which is free and open to the public (registration required), is titled “After the Forever War and the Search for Peace: Why America Needs War Literature.” Gallagher will also hold a workshop on March 18th about how creative work interacts with historical moments.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What do you think is the value of war literature?

War often seems like a destination, something that takes place elsewhere and it’s a terrible force. Which is true, but it is easy for everyday Americans to feel removed from its consequences even as our foreign policies and our elected representatives make decisions that impact people across the globe. As readers and citizens of a republic, I think war literature can connect folks to the lives of the soldiers and civilians who are living amongst war in their everyday lives, whether in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Ukraine.

War is unfortunately something that is dogging much of the world in the 21st century. What war literature can do, beyond bringing forth facts, is explore the messy grays of human existence. I consider myself anti-war but something like Ukraine comes along and I find Ukrainian resistance to be just. I think literature allows readers and writers to get away from ideological poles while considering the grayness of the subject, which can be hard in political science. It also allows the human element to take prominence.

If someone wants to write about war, how do you think they should approach it?

I’m a big believer that anyone can write about war for many reasons. Sometimes, folks feel that you need to be a military veteran or a journalist to write about war. I try to push back on that as much as possible because war is a human endeavor that is always a choice. As a result, any writer can approach the subject, but that means putting in the work to get details right, reading interviews, and reading the works of those who came before.

A great example of this is Stephen Crane’s “Red Badge of Courage.” [Crane] wasn’t a civil war veteran, but he was a journalist that was interviewing the dying generation of Civil War veterans in the 1890s, so he sat down and wrote probably the greatest American war novel. Writing is work, and if the writer is willing to put in the work, no subject is beyond their grasp.

There tends to be a divide and perhaps some resentment between soldiers and civilians. Why is it important to close that gap, and how can we do it?

It’s important [to close that gap] because this is America, and we all belong to the same republic. We all are equals, we all have one vote, and even when we disagree on all kinds of issues, at the end of the day, this country belongs to us all.

In today’s day and age of an all-volunteered force or people joining the military by choice rather than being drafted, there can be a cultural gap between soldiers and civilians. I felt it myself when I was in uniform and had my own resentments when I was in Iraq. Like anything else, it might start with smart people or just people who care sitting down and hearing each other out, even being willing to disagree because war is inherently political. I found in my work, like Words After War, that veterans, as well as civilians, should listen because someone else has a different vantage point of war and foreign policy. On a ground level, it’s been so meaningful watching people from different backgrounds coming together and finding common ground through literature.

You were in the military. How do you think we can depoliticize the military?

I think it’s important for people from all walks of life to serve in different ways. You don’t necessarily have to join the military to do that. I think about two soldiers from my scout platoons from different backgrounds who became friends simply from being in the army at the same time. I don’t think it happens enough in 21st-century America, and I worry that it happens less and less. The military is not for everyone, but everyone should still find a way to serve, whether through local communities or for an entire nation. Giving back to others can resonate with you for the rest of your life.

How should we view the war in Ukraine? What’s at stake, in your mind? Why should Americans care about the war?

I think there is some war fatigue in the American populace after two decades of the war in Afghanistan. Ukraine is its own country and this war is its own entity, dealing with genocide like the Bucha massacre, for example. There are all kinds of reports of Russians forcibly seizing Ukrainian children and transporting them.

This seems like something from another century, but it’s not, it’s happening right now. Ukraine is a sovereign nation with its own elected government and had fought for freedom. It may not be a perfect country, but neither is America. I also want to recognize the gratitude that everyday Ukrainians expressed when I was over there which was immense. I think as everyday Americans, we can show our support through financial means to various groups and even though not everyone is in a position to give financially, we can vote and with Ukraine becoming a topic that will shape the election. it’s a way of exercising this whole system of democracy.

You went to Wake Forest University. What did you major in, and how has your major influenced your life?

I was a history major and an English minor. I think that combination taught me at a young age that this world is deeply flawed, but everyday people can make a difference even if it’s not as meaningful as they hope for. It may come with compromises and regrets, but working for positive change always matters.

You entered the service through ROTC. Why did you sign up, and why did you eventually leave the service?

I joined ROTC in the fall of 2001, right before 9/11 mostly as a way to pay for school but also because since I came from a military family, service mattered to me. I was taught to care about things and find ways to give back. I didn’t know much about the Army or what I wanted to do in it, but 9/11 changed a lot of lives in my generation, including mine. So if I wanted to be in the Army, I would be at the frontlines, which is how I became a scout and platoon leader, spending fifteen months in Iraq.

I left for a couple of reasons, mainly because I realized the Army as an institution wasn’t for me, and I felt like I had done what I set out to do from over a year in combat. There were also other things in life I set out to accomplish. I’m still connected to that time, especially with training civilians in Ukraine. I have mixed feelings towards my time in the Army, but there was more good than bad. I make sure to recognize the bad because it counts, too.

Is there anything you’d like to add that we didn’t talk about?

I’m really looking forward to the Writer’s Conference, and Moravian has been fantastic in setting everything up. If anything, I want students to know this isn’t some recruiting campaign and to acknowledge that war belongs to us all whether we like it or not. Pondering about it is what will make us better thinkers and better citizens, hopefully.