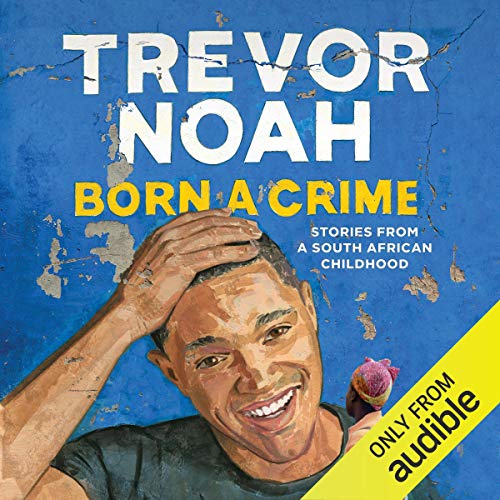

Trevor Noah released “Born a Crime” in 2016, telling the mischievous stories of his childhood during a dark part of history, showcasing his beautiful and complex relationship with his mother.

I’ll be candid and admit that I’m not the best English major when it comes to reading books outside of class requirements, but this book changed my mind. Trevor Noah redefines the expectations for a memoir, somehow providing a bright outlook with comedic undertones while retelling horrifying stories of growing up under the harsh conditions of Apartheid.

If you’re unfamiliar with Apartheid, it was the process of discriminating against the non-white majority from the rest of the South African white minority, segregating the two groups and killing thousands. For a period of almost 50 years, it was illegal for South Africans to have interracial friendships, relations, and children–and mixed children were a symbol of promiscuous criminal behavior.

This is where Noah comes into play; born a mixed child to a single black mother, he was “Born a Crime.”

I had previously researched the consequences of Apartheid, and I had done numerous projects on Nelson Mandela, yet somehow, I don’t think I truly understood the consequences until opening these pages and empathizing with an individual’s story. Numbers are often daunting but cold and hard to grasp, and these accounts are so important to remain empathetic to these events.

Noah seems to effortlessly explain years of history in a few simple sentences to provide context for many of his anecdotes–tackling the personal perspective and perseverance of black and mixed Africans while educating the reader in an easily accessible way.

Not only is his writing accessible, but it’s engaging, humorous, and entertaining, something I considered impossible regarding the weight of some topics discussed.

Above everything else, however, is Noah’s love and appreciation for his mother, the sentiments oozing off the page. Noah spent most of his childhood hiding, being pushed out of a moving car, running from the police, and evading the street criminals his family relied on. Yet, behind all of this lies the love and respect he has for his mother.

Noah masterfully plays with the reader’s emotions, telling us how his mother pushed him out of a moving car, constantly beating or reaming him. Yet, after stating these flaws, he credits how his mother did everything to protect him, even if that meant hitting the crap out of him. She knew that she beat him to protect him, to discourage him from acting out–because she would hit to teach; the cops beat to kill, especially someone of mixed descent.

What I love about this memoir is that it proves change is possible but not quite guaranteed. Noah acknowledges his mother’s faults, and after she had two more children in an abusive relationship, she changed her parenting style. Yet, her abusive husband never changed. He was a consistently intoxicated freeloader who eventually grew to beat and threaten her until he ultimately went too far.

Noah’s mother was blinded by faith, attending three different church services on Sunday and canceling her life insurance, believing God was the only insurance she needed, a statement that shattered Noah’s heart and almost his wallet. I’ve never believed in miracles, but Noah changed my mind once again. His mother is still on this earth because someone wanted her to be.

Faith has always been used as an escape from grief and childhood trauma, to the point it almost became tiring and frustrating to hear (at least to me, personally). Yet, Noah balanced faith, grief, and their connections respectfully. Faith has always been a deep and controversial topic for me, but I felt some sort of closure and catharsis from reading this.

Noah’s mother is a constant inspiration. Why give birth to an illegitimate child who would be discriminated against before birth? Because she wanted to, she wouldn’t let the government dictate another aspect of her life. She was born with the right to choose, so she decided. Why not leave the ghetto, leave South Africa? Because that place was her home. Any question or concern that Noah had, she seemed to have an answer for.

Mothers like her raise good sons, good men, and good children.

One of the quotes from his mother still sticks with me from the memoir, stating, “Learn from your past and be better because of your past. Life is full of pain. Let the pain sharpen you, but don’t hold on to it. Don’t be bitter.” And she followed that advice to a T — she didn’t transport the pains of her childhood onto Noah; she showed him the world, taught him English, and took him to activities that were only limited to “the white man.”

Despite questions and criticisms of why she would bring a mixed child to ice rinks and the suburbs in their tangerine car, she answers: “Even if he never leaves the ghetto, he will know the ghetto is not the world.”

Noah’s memoir seems to be an open letter to his mother: a marvelous, brave woman who defied expectations to provide for her family. Noah wrote lovingly, “No one chose her. She did it on her own. She found her way through sheer force of will.” He was right; no matter what life throws at his mother, she tackles it head-on and doesn’t shy away from any battle, even one as uphill as Apartheid. She had no idea if or when Apartheid would end, but she prepared Noah for a life of freedom as if it didn’t exist.

For the last section of the review, I’m going to go a little deeper into his mother’s injury, so maybe avoid reading the rest of this if you’re interested in a spoiler-free reading of the memoir. In addition, I’d like to provide a content warning for discussions of death, grief, blood and gun violence.

Noah’s mother was shot by her abusive ex-husband, first in the leg and second in the head. But there is no way to explain why the 9mm misfired four times in a row while pressed execution-style to her head, only hitting her after she started to escape. And despite being literally shot in the head, she still comforted Noah on the gurney, telling him to go find and support his younger brothers.

And she lived. By some divine miracle, the bullet managed to narrowly avoid everything important in her skull, and her ex-husband only got three years of probation after committing these atrocities.

When Noah hears that his mother was shot in the head, he internally breaks down while still driving to the hospital until he erupts into a chorus of screams and cries. I think I felt myself become so drawn to this novel, especially this section, due to its raw honesty. His mother was shot in the head; of course, he would be upset, but I wholeheartedly believe most men would rather receive a bullet than publicly show such a raw display of emotion.

Noah doesn’t just experience it; he relives it through every line he writes.

I couldn’t stop the waterworks from starting throughout multiple sections of this book, but this chapter was one of the most powerful for me. I lost my father in a hospital, and I could feel myself reliving those moments of hesitance, fear, and complete anger from Noah’s vivid descriptions, and I give him so much credit for that.

This novel was a cathartic read. I felt validated through my struggles with grief and faith, and I didn’t feel like the worst person in the world for being “mad at God” for a good portion of my childhood. Noah publicizes and normalizes these intimate and raw feelings in “Born a Crime”; it’s easy to see how it became a #1 New York Times Bestseller, winning various other accolades.

Although it may be a little heavy or an emotional read, Noah does a fantastic job breaking up the tension between these hard moments with occasional humor, helping to make it a little lighter. I would definitely recommend picking up a copy if you get a chance.

Gavin Buckley • Sep 1, 2023 at 8:39 pm

What a great review Liz; you have a such a way with words. I’ll definitely have to give this book a read.