Steelmaking in Bethlehem: A 40-Year Employee Looks Back

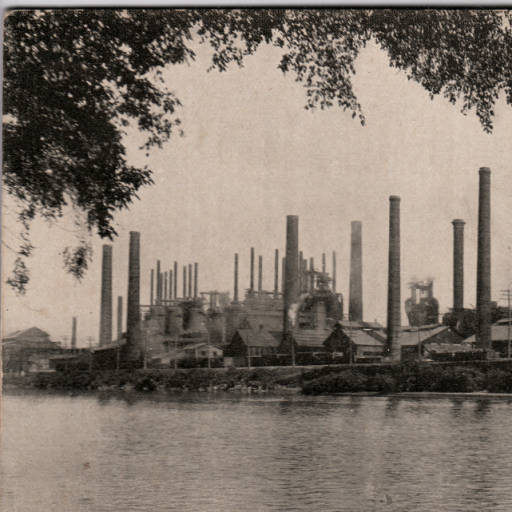

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation, once the heart of the city of Bethlehem, produced steel for some of the most famous landmarks in America: the George Washington Bridge, the Empire State Building, and the Golden Gate Bridge. Founded in 1899, the company endured for 9 decades as the country’s second-largest steel maker, before closing its doors forever.

Those of us who come to Bethlehem as outsiders see the rusting blast furnaces as part of the SteelStacks complex, which is one of the most prominent icons of both the city and the greater Lehigh Valley. For locals, however, the Stacks are a constant reminder of the past and of a steel plant that contributed to the growth of the city.

The closure of Bethlehem Steel in 1995 shook the city to its core, but perhaps the ones most affected by it were the workers themselves. I had the honor to meet one such worker who dedicated his entire working life to “The Steel.”

Leonard Ortwein, 91, a Bethlehem native, worked at Bethlehem Steel for 38 years. He retired in July of 1986, almost a decade before the plant shut down. In a recent interview, he recalled his long history as a steelworker during Bethlehem Steel’s heyday.

Born in 1927, Ortwein grew up in Southside Bethlehem, then a separate borough of the city. His youth took place during the Great Depression. Work was scarce, the union nonexistent. Workers showed up at the steel plant every day but were not guaranteed work, let alone enough for a 40-hour workweek. “Conditions were, in plain English, horrible,” recalled Ortwein.

After graduating from Bethlehem Technical High School, Ortwein went off to fight in WWII in the Pacific. When he returned home, he went straight to work at Bethlehem Steel, starting as a laborer, before eventually assuming the positions of Third Helper (rebuilding the lining of the furnace after each charge), Second Helper (cleaning the tapping spout), and finally First Helper (operating the furnace controls).

At one point, the company employed 24,000 workers at the Bethlehem plant alone and operated other plants in Lackawanna, Johnstown, Williamsport, Lebanon, South San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sparrows Point, and then its largest plant, Burns Harbor, in Burns Harbor, Indiana. Between 1940 to 1954, the entire corporation employed more than 100,000 workers.

The 1950s-60s were boom years for the Steel. “[The company] was the backbone of the Lehigh Valley,” said Ortwein. Steel produced by Bethlehem was used to help rebuild Europe after World War II and the infrastructure of a rapidly growing U.S. During this time, Bethlehem Steel began producing the iconic I-beam, which provided strong structural support for buildings such as skyscrapers.

Bethlehem stood out as a diversified plant, Ortwein said. “We had a lot of different specialty shops like forges, machine shops, and brass foundries, things that were indirectly related to steel.”

The power that Bethlehem Steel wielded in the city was immense. “The City of Bethlehem was run by the steel company,” Ortwein said. “The city didn’t do anything that was contrary to Bethlehem Steel’s wishes.”

Working at a steel plant was not without its safety hazards — Ortwein’s finger was cut off on the job — but it was rewarding, too.

“It was a good paying job, [and] you had a lot of responsibility,” he said. “It [gave me] a feeling of satisfaction.”

By the late 1960s, however, there were signs that trouble loomed for Bethlehem Steel. One of the most concerning came when the company didn’t get the contract to supply steel for the construction of the Twin Towers in New York City.

Other factors played roles, too, including foreign competition, the development of mini mills, and the mismanagement of the company, according to Ortwein.

After WWII, Japan and the other countries around the world had to rebuild their own steel mills from the ground up, and of course, they built the most modern factories. These “mini mills” used electricity to turn existing scrap metal into steel, a more efficient and inexpensive alternative to Bethlehem’s basic oxygen furnaces.

“They had the brand new mills, they had cheap labor, and we could not compete with them,” said Ortwein.

Bethlehem Steel’s location proved another liability. As a landlocked, integrated mill like Bethlehem’s, materials had to be transported to the plant.

“The most successful integrated steel mills are built [on waterways]: Pittsburgh has the Monongahela and the Allegheny and Ohio rivers for transportation, and the big mills in Chicago all have the Great Lakes with the St. Lawrence seaway of course, whereas here we had to bring everything in by rail,” said Ortwein. “So the Bethlehem plant was at a disadvantage.”

Ortwein also believes that the executives of the company managed operations poorly.

The end of steelmaking in Bethlehem happened gradually. Different plants and operations of Bethlehem Steel were shut down as they became unprofitable.

The steel plant ceased operations on November 18, 1995. At a closing ceremony, “God Bless America” played in the background.

Eventually, Sands Casino bought the plant and helped transform the area into the commercialized tourist attraction it is today.

Ortwein is not so supportive of the casino, as he is not a fan of gambling. “As far as other developments,” he said, “if it would be industry, I’d love to see that.”

Ortwein retired at 59 on July 31, 1986, when Bethlehem Steel was on the decline. He might have worked longer, but in an effort to downsize, the company began giving incentives to senior employees who were too young to collect Social Security, offering $400 per month until the workers were 62, old enough to collect that amount directly from Social Security.

“It was incentive for people like myself to take that offer and retire, which is what I did,” said Ortwein.

Ortwein then lived a comfortable retired life in Allentown with his wife. Since 1989 he has lived on the north side of Bethlehem, a block from Moravian’s campus, where he can sometimes be seen walking or relaxing on the benches.

When asked how he felt about witnessing the steel plant’s decline and eventual closing, Ortwein said, “I felt very sad. I’m sad to this day. I’ll never get over that. We had a nice living out of that steel company.”

Coming to Bethlehem after living my entire life in a small farming town, I was awed by the SteelStacks, as the old Steel plant is now called, and the juxtaposition of history and modern culture. The SteelStacks has commercialized its historical roots. I spent four years at Moravian blindly accepting the Stacks as this tourist attraction and didn’t give a second thought as to how the Stacks might exist to some as a sad and tragic reminder of the past.

Last summer, my perception changed. On a warm August night after MusikFest, when I paused to stand in the chromatic glow of the SteelStacks on the Hoover Mason Trestle, I was humbled by these majestic rusting giants that serve as a historical landmark of a time that made Bethlehem what it is today. The SteelStacks are a central monument in the Lehigh Valley but represent a larger history. While it is a poignant history injected with sadness and nostalgia of the times when Bethlehem contributed to the growth and influence of a nation, there are many who still call the Steel home.

Joseph Kohlmeier III • May 24, 2018 at 12:36 am

That is my grandfather. He talks often about the steel company. He always says it was a good place to work. I thought the article was very nice.

Steve Williams, thank you for sharing memories! • Jun 30, 2024 at 10:13 pm

I worked at burns harbor 44 years,I understand!