Summer Research Experience: Hawk Mountain Sanctuary

When starting my college journey in 2019, I knew I wanted an internship to be part of it; the work experience would be invaluable after graduation and it offered a chance to earn credits that would help me graduate earlier than my expected year.

After a long search and application process, and with help from Dr. Diane Husic, I was able to land an internship last summer as a Stewardship Intern and Invasive Specialist at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary.

There, I became part of a team responsible for various jobs relating to protecting and preserving the Sanctuary land, including everything from construction of a deer enclosure to general maintenance and upkeep of the property.

The main focus of the team, however, was the removal of invasive plant species. These invasives are responsible for considerable damage to our local forests; they crowd out, outcompete, and kill off native species that our forests depend on, which reduces the health and biodiversity of the forest.

While the team was responsible for the removal of a variety of different invasives, each coming with their own set of challenges, our primary focus was Microstegium vimineum, or stiltgrass.

Stiltgrass is a particularly nasty invasive plant that already has a hold on the Sanctuary. It

can spread quickly and completely coat forest floors, preventing almost anything else from growing in heavily-impacted areas. To combat this, we sprayed the stiltgrass with an herbicide mix in the summer months, killing it before it could reproduce and spread seeds.

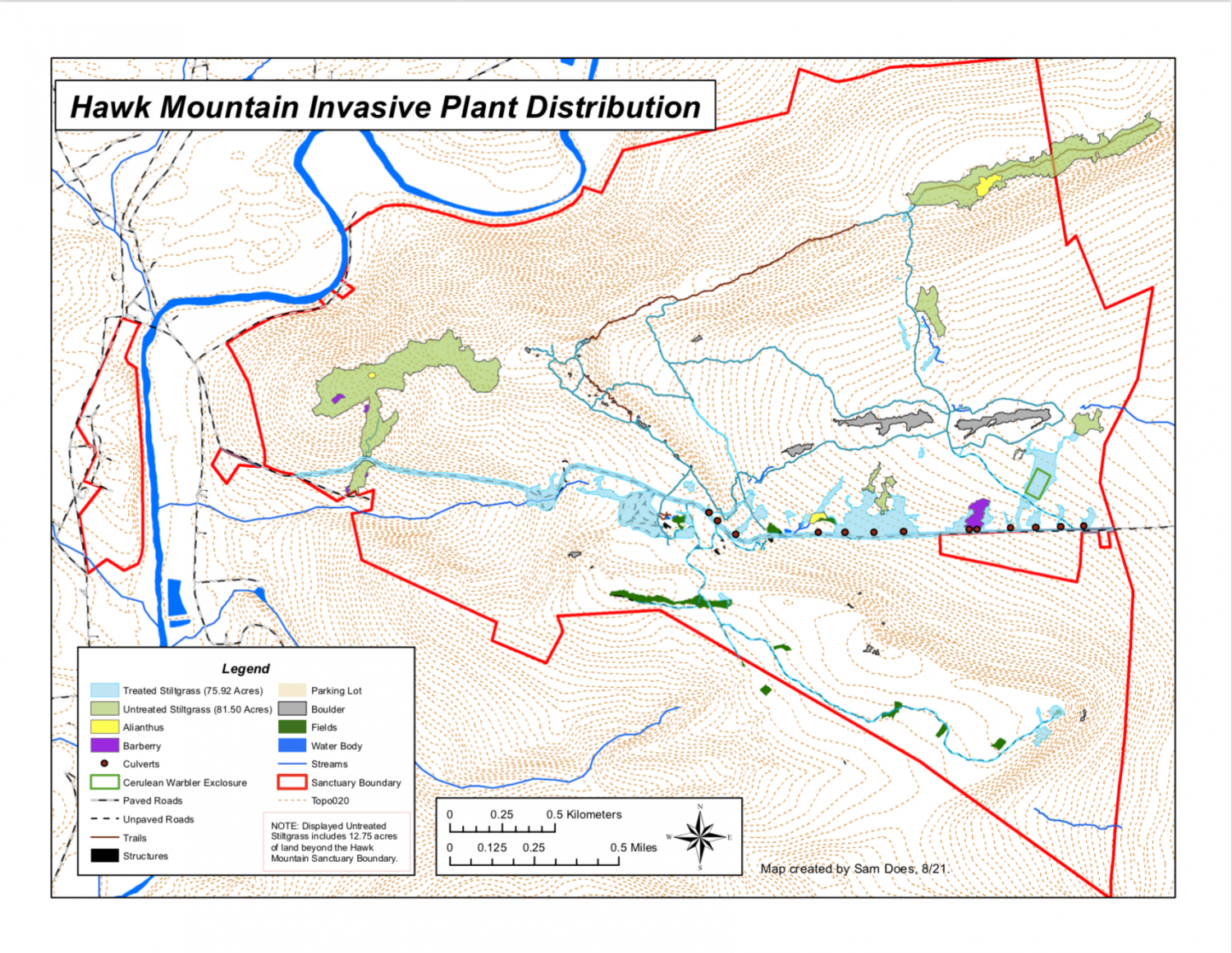

While we worked as a team to treat these impacted areas throughout the summer, it was my responsibility to produce a map of our treatment areas and known untreated stiltgrass patches. In early August, I switched my focus almost exclusively onto this new project.

The first step lasted for two weeks. For five days a week, I would grab a GPS unit and walk the perimeter of stiltgrass patches to map their extent.

A typical day consisted of about 30 minutes of planning which sites to hit, 30-60 minutes getting to the sites, and six or seven hours of mapping usually three or four different sites. Some days, one patch could take a full eight hour work day to map, while other times I could get six small perimeters done in a day.

This may seem easy at first; how hard could it be to walk a GPS unit around a perimeter?

In truth, this was the hardest part of the project. Sweltering heat (up to heat index of 105 one day), rain, mud, mountainous terrain, the occasional rattlesnake, and the pure scale of the project were all challenges in getting the locational data that I needed.

At the end of it all though, I had 50 perimeters corresponding to stiltgrass patches across the Sanctuary, which totaled over 150 acres of land roughly evenly-split between treated and untreated areas.

Once all these areas were drawn with the GPS unit, I could return to air conditioning and carry out the second half of my project. In order to make a map, all this locational data had to be combined and represented as one coherent display.

To achieve this, I utilized ArcMap. For anyone who took Intro GIS with Professor Paul Edinger, you know how difficult this aspect of the project can be.

This side of the project took just as long as the GPSing, although the dangers were limited to slow computers. All the various perimeters had to be imported to ArcMap, individually edited to ensure they accurately represented the shape and area of the stiltgrass patch, and merged together into one layer that could be symbolized and measured.

Once the data was set, colors and map elements including a north arrow and scale bar were added and marked the completion of the map.

What I found from compiling these treated and untreated areas, along with other spatial data like roads and culvert locations, was that storm water and human movement are most likely the two prevalent and most influential means of stiltgrass spread across Hawk Mountain.

Culvert locations visibly correlate with treatment areas, and the shape of nearly all areas follow the downhill slope indicating travel by moving water. Other patches were located on well-traveled trails and the parking lots indicating human transport.

While I’m not yet certain about a return next year to continue this work, the value of this map only increases with the amount of data gathered across years. More and more patterns

and correlations will become apparent as time goes on, both related to the spread of the stiltgrass and the effectiveness of the herbicide treatments.

If I do not end up returning, I hope that someone else will take up the challenge of gathering this data in order to keep the project alive.

Regardless, I hope that on future visits to the mountain I’ll see steady progress in the war against this invasive species and know that I played some role in helping to control it.

Sara J. McClelland • Oct 1, 2021 at 2:46 pm

Great article, Sam! I think this sounds like it was a really valuable experience and a great way to help conserve natural resources. You also had me laughing out loud (“…although the dangers were limited to slow computers.”)!!

Thank you for sharing this with your Moravian community.