Research Experience: Sunstones in Vasagård, Denmark

Photo courtesy of Brendon Ward

I’m a sophomore here at Moravian and a history major that is also trying to pursue a self-designed major for Anthropology.

I first became interested in studying archaeology after taking Dr. Allison Bloom’s course ANTH 113: ”Cultural Anthropology,” in which she had a lesson about archaeology. After taking this course, I looked for archaeology field schools because I felt like it would be the best option for me to learn in the field and get hands-on experience that I wouldn’t be able to get anywhere else.

My first step in getting into a field school was subscribing to a newsletter of the Institute for Field Research, IFR, which listed a variety of field schools around the world. I looked to outside sources for archaeology since Moravian doesn’t have an archaeology department. From the IFR list of possible field schools, I applied to the one at Vasagård in Denmark, since it offered an interesting insight about Neolithic life in Scandinavia.

Another aspect of the site that interested me was that it was inhabited millennia before the infamous age of the Vikings, which is usually the earliest group that students learn about in Scandinavian history. By studying the Neolithic Age in Scandinavia, I was able to learn about the foundations of society that would lead to the Vikings.

After being accepted to the field school, I had to tackle a large amount of readings that helped me prepare for the upcoming experience. The readings gave me insights into the historical context that occurred during the time period of the site, the artistic developments of the time, the theories and methods of archaeology, and the finds of other archaeological sites from nearby regions in a similar time frame. All of these different topics helped me prepare for the archaeology field school at Vasagård.

During the month of August, I attended the archaeological field school program on the Danish island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea.

The archaeological site itself is known as Vasagård and was located on a farm outside of the small town of Aakirkeby, where I stayed for the duration of the program.

The section of the causeway enclosure that my fellow students and I worked in has had multiple purposes throughout its history. It was originally used for defensive purposes to protect the settlement, but palisades, which are larger wooden fortifications made out of stakes, have been found further outside of the area which replaced the causeway enclosure. The next use is believed to be a temporary resting place for people before they were moved to the nearby grave system. After this practice fell out of use, it is believed that this enclosure was used to place broken items, which is the condition of the majority of items that were found.

During the first couple of days on site, the main objective was to clean up the excavation because it hadn’t been touched since the summer of 2019.

This mainly entailed the removal of loose dirt on the top layer and weeding grass out of the excavation area. After this process was over there were different assignments that the students worked on in groups.

One of my favorite parts of the experience was the emphasis of learning by doing since it emphasized learning hands-on instead of just looking at the material types in a book. The materials that we most commonly found were pieces of flint, ceramic, and bone. The flint was usually a shaving that was taken off of a larger piece since Neolithic people used flint to make their tools. Flint also helped construct the interactions that these people had since there were pieces of flint that were imported from different regions in Scandinavia and displayed how trade occurred during the Neolithic period.

The ceramic pieces were usually shards of broken pieces of pottery and, depending on the piece, there were designs imprinted on them. The design styles found on the ceramics actually helped determine the time period in which the site was in use, since there are a multitude of different ceramic styles throughout the Neolithic period. The styles found on the ceramics from this site are known as the Vasagård style, which dates from around 3,000-2,800 BCE.

The bones we found at the site were all believed to be remains from animals, specifically cattle. Many were in poor condition due to poor preservation in the soil, but there were some good finds with bones that were better preserved. Since many of the objects were very fragile, we worked with delicate tools like small paint brushes, dental picks, and small trowels. We also had to make sure to dig carefully in the causeway enclosure in order to keep the artifact as whole as possible.

Digging in the excavation took up the majority of my time at the site, but I also sifted,

sorted, and did 3D modeling. Sifting comes after digging, and when a student cleans up the loose dirt from the area where they were working. The loose materials from the area where the student dug is put into a bucket and then placed on a rocking sifting screen where the dirt is separated from the more dense materials.

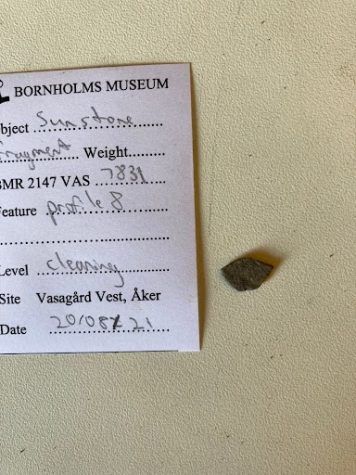

After this the leftover materials are placed on a tray to dry and are given a tag with its VAS number (ID number), location where it was found, the date, and the initials of who found it.

After sifting, the students then sorted the different materials from the tray and group similar artifacts together. Then, the grouped materials are placed in a plastic bag with the tag that has the same information as before, except that it also has a material type label on it.

Another aspect of working at the excavation was the use of 3D modeling of the site to help identify the location of artifacts.

This is done by taking a series of photographs at different angles of an area and then putting those photos in a digital software that creates a 3D model. Another tool that helped with the 3D modeling process used GPS to mark objects on the site. This additional tool is known as a total station, which is very useful to help measure where the objects are and how deep the artifacts were located in the soil. The incorporation of modern technology in the field of archaeology helps with the analysis of artifacts and how location plays a part of settlement planning.

One of the larger artifacts we found in the causeway enclosure are Sunstones, which are made out of a slate material and were scratched, making tally-like marks or ladder shapes. These are believed to be used for religious purposes for a sun-based religion and for burials. During the final parts of the burial ritual the Sunstones were placed with the decorated side facing down. These were important finds because they represent how these people began to focus on things away from basic survival.

As for my future plans in doing archaeological research, the school directors from Vasagård invited the students to come next summer to a different site at Sorte Muld, which is a Viking-age site. Although I am currently uncertain if I will go back, I am still interested. Also for my self-designed major of anthropology I have the possibility to pursue honor research projects during my senior year. Although I don’t know what I want to dedicate the project to, it will certainly involve the use of archaeology.

Summer research internships can involve a lot of risk. I knew that when I first started pursuing this opportunity that it wouldn’t be easy, especially since I did a lot of the setup on my own. I’ve never done anything like this before, let alone going to a field school but also travelling to a different continent for the first time.

I won’t lie and say that I wasn’t nervous for this experience, but looking back at it I am really proud of what I was able to accomplish.

That’s why I encourage people to pursue internships, since I believe that they can help students gain experience in their possible fields of interest outside of the classroom. This is also why I did a separate internship this summer with the local National Museum of Industrial History. Whether or not a student wants to study abroad or attend a nearby internship is up to them, but I encourage them to gain as much experience as possible so they can be as fully prepared for their future careers.