Meanwhile, in Ireland: The Personification of Ireland

from Irishstudies.org

ATTENTION: This article contains spoilers for the play Cathleen Ni Houlihan by W.B. Yeats and Lady Augusta Gregory. Be advised that if you do not want spoilers for this play, please feel free to skip this article.

Ireland has long been seen as more than a country. Over the millennia, one thing has remained the same, though in different incarnations. In the past couple of decades, there was Eimear Quinn’s song The Voice and Loreena McKennitt’s The Wind that Shakes the Barley, originally a poem from 1861 by Robert Dwyer Joyce. In the days of the Gaelic Cultural Awakening in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there was the depiction of Cathleen Ni Houlihan (also spelled Kathleen Ni Houlihan). And in the days of Gaelic Ireland, the era from 1607 back, there was Eriu and her sisters, Banba and Fodla. What all these have in common is that they are incarnations of the spirit of Ireland itself.

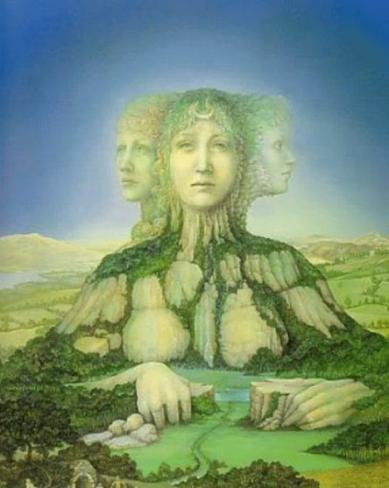

The name, Ireland, itself is derived from the goddess Eriu, or Éire in modern Irish. Additionally, in the Irish language, Ireland is sometimes referred to by the names of Eriu’s sisters, Banba and Fodla. According to folklore, long before there were humans in Ireland, Eriu, Banba, and Fodla, daughters of Ernmas, and the half-sisters of the great goddess of war and death, The Morrígan, faced enemies who came to their shores, the Milesians. The Milesians tried to take the land for themselves and push the tribe that Eriu and her sisters belonged to, the Tuatha de Danann, out of Ireland. But the three took a stand and were able to defend Ireland for a time. Being the heroes of the land, they gave their names to it . Eriu, as the leader among the three, became the most predominantly used name, with Banba and Fodla as alternative names in the Irish language. Some say Eriu even became the island itself.

Cathleen Ni Houlihan was a character first introduced in a poem, but more famously appeared in an Abbey Theatre play by W.B. Yeats and Lady Augusta Gregory with which it shares her name. Cathleen appears in the majority of the play as a frail, little old lady who explains to the main character that she was forced from her home and her neighbors stole her four fields from her, all the while singing songs featuring the heroics and tragic deaths of the men who had tried to defend her land for her from these cruel neighbors. In the first run of the play within the Abbey Theatre, Cathleen was portrayed by actress Maud Gonne, who herself would become deeply involved in the larger Irish Independence Movement of the early 20th century, such as during the 1916 Easter Rising.

![Maud Gonne [center] as Cathleen Ni Houlihan, from Wikipedia](https://comenian.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/unnamed-1-1.jpeg)

In The Voice by Eimear Quinn, this spirit of Ireland acts as the narrator, calling to the listener. Similarly, it appears in The Wind that Shakes the Barley, a song by Loreena McKennitt that features the words of a poem of the same name. This poem was written by Robert Dwyer Joyce, in 1861, only a decade following an Gorta Mór, the Great Hunger. In the song, set in the time of the 1797 Rebellion, the narrator describes the murder of his true love, Ireland itself, which prompts his deep contemplation over his loyalty to and the deep emotions he had for his true love. This is the catalyst for him to take a stand for his true love, even though he knows he will likely join her in death for his actions. Referenced is Oulart Hollow, or Oulart Hill, one of the more notable battles of the 1797 Rebellion.

‘Twas blood for blood without remorse

I took at Oulart Hollow

I placed my true love’s clay-cold corpse

Where I full soon may follow

Around her grave I wandered drear

Noon, night and morning early

With aching heart when e’er I hear

The wind that shakes the barley

(from The Wind that Shakes the Barley by Loreena McKennitt)

There is a similar note to be observed in The Voice, though one should also note the era in which the song was written. It was written for the 1996 Eurovision song contest, putting it only a short two years before the Good Friday Agreement was signed, ending the active Troubles. Particularly poignant and significant in regards to this era in which it was written is the third verse:

I am the voice of the past that will always be

Filled with my sorrow and blood in my fields

I am the voice of the future

Bring me your peace, bring me your peace

And my wounds, they will heal…

(from The Voice by Eimear Quinn)

These two songs’ perspectives echo with Cathleen Ni Houlihan, which itself was drawn from the old stories of Eriu and her sisters, their brave defense of Ireland from foreign invaders becoming a point of inspiration over the centuries. In Cathleen Ni Houlihan, Cathleen appears as an old woman as a way to test the true loyalties of the main character, if he would give up everything to aid her. It’s only at the very end when the main character chooses to pledge his loyalty to her and follow her wholeheartedly that she shows her true form – youthful, beautiful, and above all else, she is described as walking like a queen.

One could easily draw the comparison of this depiction to how Ireland itself was viewed in that day and age. Ireland, by the start of the 20th century, was the poorest region in all of Europe, the collective result of great suffering for centuries prior, with the four kingdoms, now called provinces, being stolen by the neighbors. But there was a shining queen underneath, a beautiful and rich past overshadowed by the state she currently stood in. It is this past that many wanted to restore and the cause they were loyal to, to the true Ireland that remained, clinging underneath the trauma and the appearance it created. This call for complete loyalty, even if it means sacrificing everything, repeats in both of the aforementioned songs, with the former calling to the listener, and the latter to a character within the narrative of the song. The latter also shares with Cathleen Ni Houlihan the idea of Ireland being the “true love” of the people who are loyal to her. Ireland is more than a country, or a chunk of land sticking out from the ocean, but rather a living being who has long suffered, and loyalty to the nation means loyalty to this spirit itself, an ancient warrior queen taking a stand and defending her home.