Meanwhile, in Ireland: Come Away, Oh Human Child (The Whisking Away of Children to the Otherworld)

(Slish Wood Lake from sligowalks.ie)

Come Away, Oh Human Child

To the waters and the wilds

With a fairy hand in hand

For the world’s more full of weeping

Then you can understand…

(from “The Stolen Child” by W.B. Yeats)

The folk tradition of the mischievous faerie has long existed across Ireland. The west coast particularly held a deep fear and fascination with them. Perhaps the otherworldly wonders of the west coast fed into this sense of connection between our world and the Otherworld, or the realms where the supernatural beings reside. Halloween began there as a festival called Samhain (pronounced Saw+in), meaning “Summer’s end.” It was the point of the year when the old year died and a new year was born. This festival marking the end of the harvest and beginning of the darkness of winter was born from the belief of these faerie creatures known as the Sídhe (pronounced Shee), Aoi Sídhe (pronounced Ay Shee), or Daoine Sídhe (pronounced Dee+Nuh Shee) in Irish, meaning “people of the mounds,” causing havoc among the human folk. The belief was on this day, the veil between the worlds was at its thinnest point and could most easily cross over. On this day, the Sídhe would attempt to wish away the human children. In order to prevent these “faerie-nappings,” the adults of the villages would disguise their children as these faeries in order to try to trick them into thinking the child was one of their own kind; thus was born the tradition of dressing up on Halloween night.

The whisking away of human children to the Otherworld by the Sídhe was not limited to only Samhain night, however. Everyday traditions and habits began to form, most prevalent on the west coast. For example, it was believed that boys were more likely to be kidnapped by the Sídhe. A tradition came about of dressing young boys in petticoat skirts until they were 8-12 years old, or otherwise considered to be strong enough to defend themselves. This was a practice that could still be observed in places like Clare, Galway, Mayo, and Sligo, along the west coast, through the 1960s.

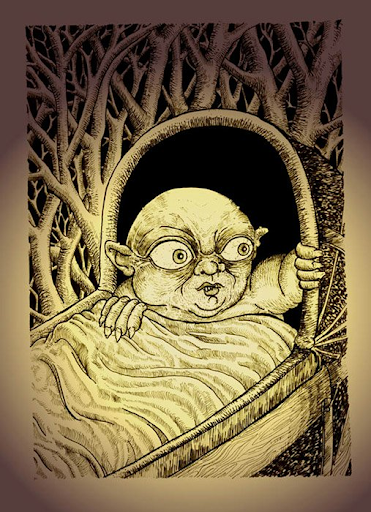

It was also believed, beginning in the middle ages, that unguarded infants could even be taken. They would be replaced by a baby of the Sídhe, with the common purpose of the Sídhe wanting the human mother to become a nursemaid for the Sídhe baby. In some stories, human women are taken away into the Otherworld to act as nursemaids for Sídhe children, or even be married off to become queens of the Sídhe realms. In the song “A Bhean Úd Thíós,” (pronounced Awe Vawn OOD EES), a human woman is taken to the Otherworld and was to be married off and become the Queen of the Sídhe if her husband did not come for her.

The Sídhe babies put in the place of stolen human infants are known as Changelings, a creature that appears all across the seven Celtic Nations, not just in Ireland. The unfortunate reality of the Changelings, however, is based in reality, outside the realm of folklore. In many places, though certainly not everywhere, children who began displaying signs of various mental or physical ailments or deformities were labeled as Changelings.

Many of the Sídhe were considered to be bearers of misfortune, were troublesome tricksters, and enjoyed causing mischief among the humans. So strong was the belief in these mischievous faerie folk that it even affected language and music. In many places, it was considered taboo to call the faerie folk faeries. Alternatives like na daoine maithe (pronounced Naw Dee+nuh Meye+uh), meaning “the good people,” or na daoine uaisle (pronounced Naw Dee+nuh OOsh+leh), meaning “the noble people,” were commonplace.

A song called Seoithín Seo (pronounced Show+EEN Shyo) displays this mischievous side of the faerie folk. In short, the lyrics warn the child who is being sung this lullaby to go to sleep immediately or else the faeries, lurking just outside the house, will come and take them away. Musicians Joe Éinniú (pronounced Eye+Knee) and Cormac de Barra, who have performed versions of Seoithín Seo, and many others, recall their mothers and grandmothers lulling their children and grandchildren to sleep with this song with the preface of the faeries up on the roof. If you closed your eyes and went to sleep, they would leave you alone. But if you did not, they were waiting to come take you away to the Otherworld.

Not all folk narratives involving the Sídhe involved mischievous Sídhe, however. Poems like “The Stolen Child,” written by famed Irish poet W.B. Yeats, also came about. In this poem, set in the realm of County Sligo, a young boy is spirited away by a faerie. A more positively-natured Sídhe is at the core of this poetic narrative. The faerie in the poem sees the darkness in the world and wishes to protect a young boy it had been keeping a watchful eye on. So it lures the boy away and into the Otherworld, which is presented as a magical, inviting, and peaceful place. Perhaps one of the most impactful parts of this poem outside of the repeating “chorus” is the second stanza:

Where the wave of moonlight glosses

The dim gray sands with light,

Far off by furthest Rosses

We foot it all the night,

Weaving olden dances

Mingling hands and mingling glances

Till the moon has taken flight;

To and fro we leap

And chase the frothy bubbles,

While the world is full of troubles

And anxious in its sleep.

(from The Stolen Child by W.B. Yeats)