A Sense of Place, Part III: “Reading” the Brethren’s House

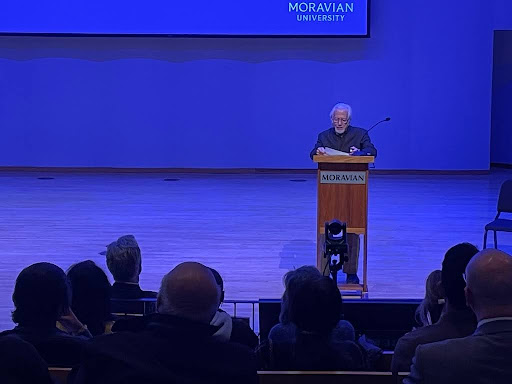

Photo courtesy of Connor Griffon

Overall, at this morning hour, downtown Bethlehem felt desolate and almost eerily vacant as heavy gray clouds hung above the Brethren’s House, a historic building that once served as a sanctuary for George Washington’s wounded troops during the Revolutionary War in the winters of 1776 through 1778.

In addition to providing refuge for the Continental Army, the Brethren’s House became a “place” for the Moravian Seminary for Young Ladies in 1815. Serving as a women’s dormitory, as well as housing a library and various meeting rooms, this building reflected the Moravian culture of communal living and learning.

The building ultimately became a part of Moravian College and its Theological Seminary in 1954 as a result of a merger. This light-stoned historic building located at the fork in the road at the bottom of the hill on Main Street deeply contrasted against the darker brick buildings flanking it.

A striking aspect of the building is that there are two burgundy entry doors located side-by-side of each other, despite the fact that the building is one contiguous structure. The true purpose of this double entryway remains unknown, but one can assume it was used to divide the building into two distinct sections based on the discourse communities – a group that shares common ideologies, goals, values, and beliefs – using the building at some point in time.

As this architecturally beautiful building has withstood the weathering elements over the years, it has had the opportunity to provide shelter to many different past and present discourse communities.

Indeed, although various discourse communities (such as the Moravians and the first women of Moravian College) have long since passed, they have left their mark behind on the collection of “genres” – such as texts, books, signage – that constitute the current Brethren’s House of Moravian University. With this inheritance, current Moravian students, such as myself, have the opportunity to interpret the genres left behind and leave their mark on future inhabitants.

Interestingly, one genre was intentionally removed by the Moravian community in the late 1700s while the building was employed as a lodging house for single men due to a fear that the genre would be misinterpreted by outsiders of the Moravian discourse community, thereby reflecting poorly on the Moravian discourse community.

Specifically, there was a plaque over the double front doors that was inscribed with the German phrase, “Vater und Mutter, Lieber und Mann, Habt vom Ehr Jünglings Plan.” Translated in English, this religious phrase means “Father and Mother and dear husband, be honored by the young men’s plan.”

At the time, people outside the Moravian discourse community who were visiting the area were fluent in German and had the opportunity to read and reflect upon the genre.

Various members of the discourse community were uncomfortable with the wording, possibly due to the fact that the trilogy (with the “mother” being the “holy spirit” and “dear husband” equating to “Jesus”) referred to Jesus Christ as the husband of single men, according to PaulPeucker, director and archivist of the Moravian Archives.

Knowing that genres reflect upon the discourse community espousing them, the Moravians feared that future inhabitants and visitors to the area would misinterpret the Moravians’ inscribed message, thereby “tarnishing their reputations.” Consequently, the rough stone plaque was chiseled out, leaving a gaping hole in the exterior of the building.

Even though the Moravians intended to erase this genre permanently, historians have since restored the plaque to its original form, and it is once again affixed to the building in its original location. However, unlike previous discourse communities inhabiting Bethlehem in the late 1700s and 1800s, the present Bethlehem discourse communities primarily speak English rather than German, resulting in very few individuals within the Bethlehem discourse community being able to read and directly understand the meaning of the inscription.

Instead, the current Bethlehem discourse community values the plaque purely for its aesthetic nature and not for its supposed religious context. This demonstrates that writers must be cognizant that genres can be interpreted differently by divergent discourse communities over time and that the writer’s intended meaning is not always conveyed as intended.