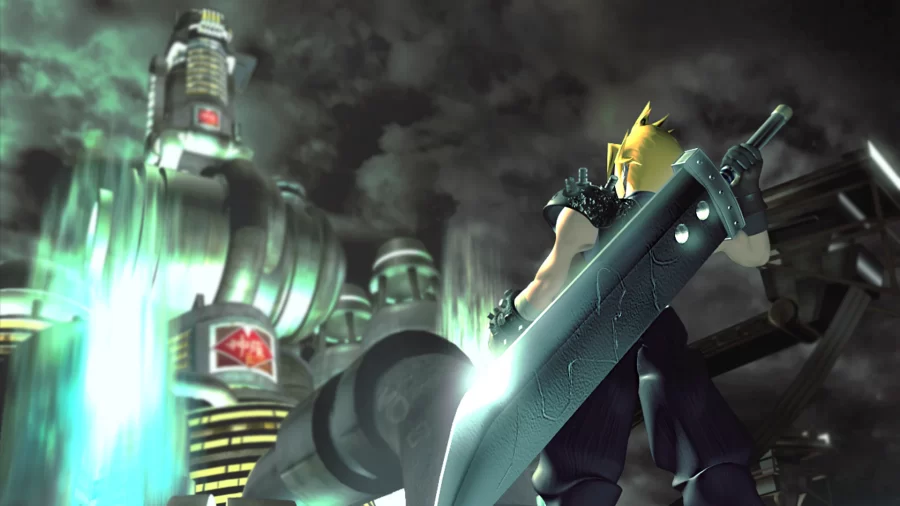

‘Final Fantasy VII’ Part 1 – A Message in the Clouds

Released on the PlayStation in 1997, “Final Fantasy VII” was the seventh installment in the “Final Fantasy” franchise of games. Developed by the Japanese video game company Square Enix, its successes in storytelling and worldbuilding spawned spin-offs and elevated the series to new heights. Today, the “Final Fantasy” franchise is booming, largely in part because of the seventh installment. This analysis (split into two parts) looks at “Final Fantasy VII” and sees what made it resonate with so many people. Specifically, it looks at the pathos (emotional appeal) of the game and the main character of Cloud Strife. Part one unpacks the message that the game gives to the player through the use of characters and worldbuilding. Part two looks at how this goes hand-in-hand with noticing the effects that the game has on its players, along with examining how this game can be used to teach a valuable life lesson for not only the people who’ve experienced the game but for everyone. Finally, the article will end by considering how “Final Fantasy VII” has impacted the gaming industry as a whole.

Sonja Foss, who wrote the book “Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration and Practice,” claims that a narrative critic looks at a narrative’s primary objective, then analyzes features of the narrative that complete said objective. Narratives can create stories that audiences can then use to acknowledge situations in their world. Alongside this, it’s also crucial to understand the emotional appeal in narratives or pathos. A rhetorical scholar by the name of Joseph Colavito writes that “The place of pathos in the rhetorical tradition is a significant one; emotional appeals constitute a crucial intersection among audience, rhetor, and subject matter, so the connection between audience analysis and rhetorical purpose comes to be an important component of the construction of emotional appeals.” What this means is that we can look directly at the pathos to understand how the objective of the narrative is directly connected to the audience.

In Herrick’s “The History and Theory of Rhetoric: An Introduction,” he uses claims from Kenneth Burke’s work, which says that humans are only persuaded if the one persuading them is “talking the same language as them,” both figuratively and literally. He refers to this as “identification.” The identification is important because it cements a basis for how “Final Fantasy VII”, or any narrative for that matter, is able to reach out to an audience. This, in turn, can alter how we as an audience perceive the world and interact with communities, whether it be through symbols or terms.

Herrick also mentions Brian Boyed, who discusses how narratives can seed a shared experience between audiences. This, in turn, allows for the identification aspect to stretch beyond just the primary audience and into people who may not have such a direct connection to the primary source. As humans are storytellers, it stands to reason that narratives spread across audiences and communities.

These rhetorical ideas and theories allow for a narrative criticism of “Final Fantasy VII” to help bring forth the message that the game wishes for the player to hear. Alongside pathos relating to the main character of Cloud Strife, using a narrative criticism outlined by Foss can allow us to look deeper into the narrative of “Final Fantasy VII” to see what aspects of it help relay its intended message to the audience. Additionally, we can use this analysis to understand how “Final Fantasy VII” uses identification to directly connect to its audience, thus making the message more personal. We can also see how this specific identification can grow to encompass as many people as possible, even those who aren’t directly involved. These rhetorical ideas are the basis of how the audience perceives the message, how effective it is, and how it can impact the future.

“Final Fantasy VII” uses the main character of Cloud Strife as a vessel to teach the audience about trust. The plot of the game follows Cloud Strife as he navigates a fantastical world on a quest to stop the evil Sephiroth. On paper, this sounds like any other fantasy story, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. The game forces the player to view the world through Cloud’s eyes, but we learn late in the game that Cloud’s eyes are tainted. All of Cloud’s memories, all of his actions, and all of his words are built on lies. This is due to the fact that Cloud’s mind is broken, and the trauma he has faced causes him to repress his memories. At the beginning of the game, he is a cold and untrusting person who refuses to keep anyone close to him. This is because of his PTSD, caused by an assortment of past trauma and fear, which causes him to look out for only himself.

Cloud’s story, in the beginning, is that he was a soldier for the evil corporation, Shinra, but left after an incident involving a powerful man named Sephiroth going insane and ultimately dying. We learn how Cloud was a top-class soldier and how his childhood home was destroyed after Sephiroth went crazy. This is our invitation into the world, but it is not based on truth. We learn later in the game that Cloud was a low-ranking soldier who watched as Sephiroth went on a rampage. He was then used as a test subject in an experiment which caused his memories and worldview to shift. Not only does this altered view distort the player’s view, but it also serves to allow the player to relate to Cloud on a personal level. This is where we can begin to acknowledge how pathos relates to the game’s message. Having experienced these events with Cloud, the player forms an emotional connection with him. As stated earlier, pathos is where a crucial connection between the audience and the subject is formed. This connection between the player and Cloud allows for anything that Cloud may experience and learn is then transferred onto the player. The inclusion of pathos gives way for lessons to be taught to the player that otherwise would have gone unlearned.

The view that the player has is how the message of “Final Fantasy VII” is communicated. “Final Fantasy VII” is a role-playing game RPG. In an RPG, the player steps into the shoes of the main character and has control over their actions. For example, a player may choose to completely ignore the main objective and fight monsters, whereas another player may choose to ignore everything else besides the main objective. RPGs are typically categorized by their focus on plot and character development over the course of a decently long time. Simon Parkin, a writer for The New Yorker, wrote this regarding the genre of RPGs: “It is no accident that the role-playing game should provide this heady combination of empowerment and refuge. These are games that slot into the ancient tradition of heroic fiction. They promise manifest destiny, a route to inevitable victory, so long as you dutifully follow the story’s thread, play by the rules and invest the appropriate amount of time.” What this can tell us is that the RPG genre can captivate its audience by pledging that they will have the opportunity to explore a new world like a fictional hero. This idea of exploration and discovery is how a player is endowed with a wanting to play.

In regards to “Final Fantasy VII” as an RPG, it encourages the use of player freedom. Each character can equip any materia, which allows the use of skills and magic. This means that a character with a low magic stat can still use the most powerful magic spell. Gerald Voorhees, who writes for the video game journal Game Studies acknowledges this idea. “It facilitates a great deal of freedom in the process of character development, which is traditionally a linear growth along a predetermined path.” Since character development plays a crucial role in the plot and message of “Final Fantasy VII”, having the ability to freely choose how a character can function creates a wide sense of attachment. This attachment to characters is what allows the message and theme of trust to become clear to the player.

The party of “Final Fantasy VII” includes Tifa, Barret, Aerith, Red XIII, Yuffie, Cait Sith, Vincent, and Cid. As the game progresses, we spend time with these characters as they learn to first trust themselves and, eventually, Cloud. Cloud, on the other hand, keeps to himself for most of the game. He finds solace in Aerith’s company, opening up to her even when he doesn’t seem to open up to anyone else. She shows him kindness he isn’t used to, which allows him to feel comfort towards her. He begins to trust her until she is stabbed through the stomach by Sephiroth, killing her. Her death plagues Cloud and reinforces his hatred for Sephiroth. He informs his team that he is going to fight Sephiroth and asks them to help him. This is the first time we actually see Cloud open up to his team besides Aerith, and it creates a sense of satisfaction.

The player is meant to embody the character of Cloud. Racheal Hutchinson examines this idea and finds that the emotional involvement in the narrative is tied to how the player has spent time with Cloud. The sudden death of Areith has implications on the player not only narratively but also gameplay-wise. If the player leveled up Aerith and spent time developing her, all their progress is lost when she dies. The mourning of a beloved character is accompanied by frustration that she can no longer be used to fight battles. This helps to invest the player in the game, as they can relate to all the emotions the Cloud is also feeling. It helps cement that the player is filling the role of Cloud.

There is a moment in the game where Cloud is unplayable due to being poisoned. We take control of the other party members besides Tifa, who opts to stay with Cloud. The other members continue to fight, putting their trust in Cloud and carrying on his mission. The trust that they gained in Cloud is what allows them to carry on the mission. This moment shows the player how much power trust can hold, even when the person you trust is hurt. With Tifa, the player peers into Cloud’s psyche to find the broken pieces and restore it to normal. Not only does it serve to fill in the blanks, but to reveal the truth to the player, the same as for Cloud. Hutchinson writes that this disrupts the player-character identification that has been building the entire game prior to this. We learn the truth with Cloud, the person we’ve spent so much time with. We understand his pain and fear because we understand what caused it in the first place. We’ve watched him grow from a cold and lonely mercenary to a helpful and caring friend. Tifa was Cloud’s childhood friend and someone he loved. He left his hometown to get stronger in hopes that Tifa would love him back. When Sephiroth destroyed everything and almost killed Tifa, he blamed himself and shut his emotions and relationships away.

Audiences can relate to Cloud the same way they can relate to themselves. Cloud’s past was buried as he didn’t wish to remember the pain, just as we try to bury the painful parts of our pasts. Aaron Hess, a rhetorical scholar, claims that this immersion into the text (Cloud’s broken mind) causes a sense of immediacy. Their example is of the Holocaust and Pearl Harbor. “Similarly, the placement of gamers inside a victim’s perspective on Pearl Harbor distracts from the politics of war and instead focuses on the need for counterattack and vengeance” (Hess 352). What this means is that as we view Cloud’s mind and see the pain he’s gone through, we feel for him and strengthen our resolve to see his cause through. As a victim, we want to help Cloud move past his false memories and into the future. Maybe we can’t all wield a giant sword like him, but we can sympathize with his mentality.

The objective of the narrative becomes much more clear here. When the player realizes that there’s a filter over Cloud’s worldview, he becomes an unreliable narrator. Foss mentions that an objective can be derived from the narrator, assuming they aren’t trying to deceive the audience. However, any semblance of Cloud being able to tell the audience the objective is gone at this moment. It is here that the objective of the narrative cannot come from the narrator because the narrator has been unreliable. This then begs the question, what is the objective? After experiencing this moment with Cloud, we as the player reflect on his life leading up to the moment, along with our time playing the game. The player had been lied to up to that point, and the only reason that the truth was revealed was due to Cloud overcoming his pain and suffering, partly due to the help of the people he trusted. Reflecting on the plot like this reveals that the narrative’s objective the entire time was to convey a message to the player, one that includes trusting oneself and one’s friends.

I know that was pretty long with multiple chunks of text. If you’ve made it this far, I truly commend you. I hate having to end this without painting the full picture, but unfortunately, there is too much content for a single article. Part two will complete the narrative criticism, so please look forward to it!