“Welcome, Neighbor” Panel Celebrates Immigrants

Four collaborators with The Collective Memory Project joined students and faculty at Moravian College for a panel discussion and question-and-answer session at the Lunch and Learn event on Oct. 26.

The project is a shared effort between many members of the Lehigh Valley community, including residents, educators, activists, and nonprofit organizations, who aim to put “a human face” on immigration by interviewing and photographing local immigrants.

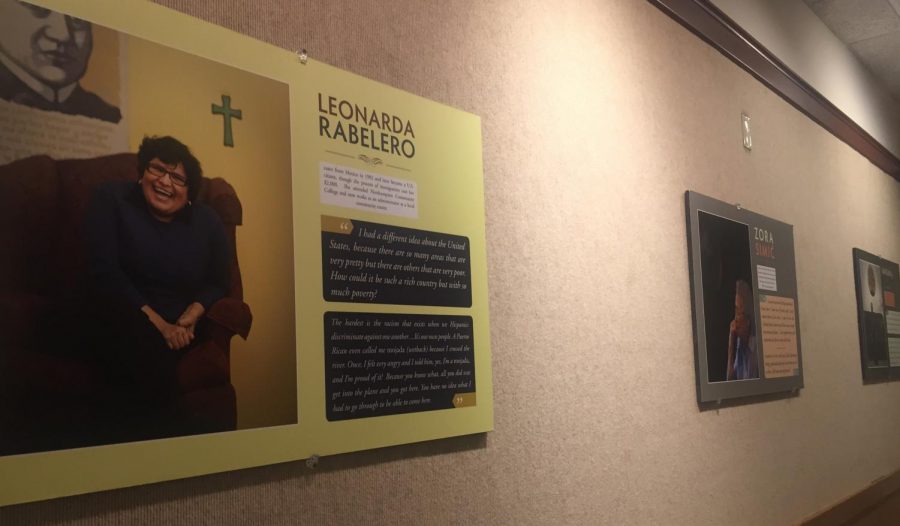

The portraits are arranged as individual posters, featuring the names of those pictured, a brief description of their experience as immigrants, and one or two quotes pulled from their interviews. The exhibit, “Welcome, Neighbor,” is currently hanging in the HUB.

The audience, diverse in age and race, took up every chair and left many people standing in the tightly-packed UBC room. The panel featured Dr. Sandra Aguilar, professor of history at Moravian College, Dr. Hugo Ceron, professor of sociology at Lehigh University, Lehigh and Moravian alumna Sarah White, and photographer Marco Calderon.

One at a time, they explained how they became involved in the Collective Memory Project, their role, and what they have learned from their experience.

Dr. Aguilar, who moderated the panel and later the question-and-answer session, kept her remarks to a brief history of the project. She joined the Collective Memory Project team, which included Dr. Ceron and Marco Calderon, at its inception in 2011. While the immigration debate often comes down to numbers and statistics, she said, the project aims to humanize immigrants by focusing on their stories as individuals with loved ones and dreams.

The inspiration for the title of the exhibit, “Welcome, Neighbor,” comes from their choice to spotlight members of the community, putting immigration into context as a local issue. To conclude, Dr. Aguilar stated that the project’s mission to inspire empathy and compassion for immigrants is now “more important than ever.”

“This is a nation of immigrants,” she said. “Immigrants are your neighbors.”

While teaching as an adjunct sociology professor at Moravian College in Fall 2010, Dr. Ceron charged his students with arranging and conducting interviews with local immigrants.

The first step, he said, was to find out how his students felt about immigration to begin with.

He found that in general, they had negative feelings towards immigrants, consistent with the messages they got from the media. But this changed as the twenty-two students conducted their forty-to-ninety minute interviews: the experience of meeting, listening to, and connecting with immigrants was powerful enough to challenge their preconceptions.

At the end of the semester, the students had very different opinions to the same questions they had been asked at the beginning. They had a better understanding of the complexities of migration and were much more likely to empathize with immigrants.

Dr. Ceron also noted that he has learned from the project as well. An immigrant himself, he was astonished by the stories of immigrants who left their homes or loved ones behind, sometimes desperate to find jobs and send money home, or sometimes to flee danger. Some people interviewed for the project had left their homes and families knowing they would never be able to return.

“I deeply respect people who do that,” he said.

Sarah White, a former student of both Dr. Aguilar and Dr. Ceron, has focused her graduate research on racial profiling, which, she argued, influences how we view immigrants. In terms of motive and character, there is little difference between the immigrants of the past and the immigrants of today. Instead, we as a society have consciously made the choice of which groups to stereotype.

White described the history of racial stereotyping in our country, where the suspicion of immigrants has shifted with each new group, using the nineteenth-century waves of German, Irish and Italian immigrants as examples. She explained that the prejudice toward new immigrants is fueled by pressure on the immigrants that came before to assimilate into society, often at the expense of their culture and even their language within a few generations. Then, to cement their place as Americans, they would eventually contribute to the effort to push out the more recent immigrants.

“They say, we are no longer the ‘other.’ Someone else has to be the other,” she said.

White also highlighted the role of language, from racialized terms like “illegal alien” to the inaccurate idea of our ancestors immigrating “the right way,” in allowing us to believe immigrants are fundamentally different or bad people. For this reason, it was important for the interviewers to be especially aware of projecting stereotypes onto the immigrants they interviewed, or making judgments about who is American or not.

Marco Calderon spoke of his experience as the project’s photographer, as well as his experience as an immigrant. Calderon, who was born in Mexico, worked in photography, radio and other media before moving to the United States eight years ago. He and his wife, an American, made the decision to move from Mexico to the United States in order to pay off her student loans– difficult to do using pesos, he added.

After struggling to find work, Calderon was approached by the ACLU, who offered him the opportunity to work with the Collective Memory Project. He calls it a “dream job” that changed his relationship with photography from just a job to a passion.

Calderon took photographs during the interviews. His ideal photos reflect both the subject matter of their interviews and the personalities of the subject, but it was not always easy to find a balance between the two.

He named Leonarda Rabelero as an example of this conflict: she is pictured laughing, but her quotes address poverty in the United States and the racism she has experienced from other Latinos. Calderon also said that forming connections with the interviewees allowed him to take the best possible photographs, and that it became easier to find common ground after he had children.

“I can talk family with them,” he said. “An immigrant has a family.”

Most of the subjects see their portraits for the first time at the “Welcome, Neighbor” exhibit. Calderon always asks them if they “see themselves” in their pictures. He mentioned Chiharu Tokura– pictured, laughing, on the stairs in her home– as one of the many who have said that they do.

On the process of collecting the oral histories of the immigrants and creating the gallery, Dr. Ceron stated that deciding which brief quote and photograph should be featured was “the most difficult part.” Some subjects did not want to talk about painful events in their lives or felt conflicted about being interviewed as an immigrant.

One subject’s very negative views on new immigrants created a conflict for the team, which had to choose what to highlight to accurately reflect the subject’s experience without undermining the project altogether. But the open-ended interviews gave all the immigrants a chance to speak freely about their experiences and be heard.

The Collective Memory Project, including all interviews and photographs, is archived at Lehigh University. Students are invited to use the materials for research and can contact Dr. Aguilar if interested. The “Welcome, Neighbor” exhibit is currently on display in the HUB.

Sandra Aguilar • Dec 6, 2017 at 9:49 am

Thank you for reporting on this event.