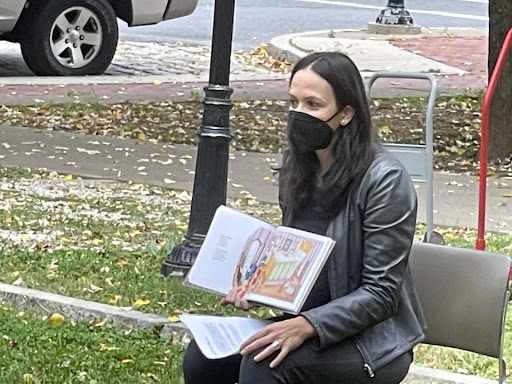

On Sept. 18, Dr. Kin Cheung, Associate Professor of East and South Asian Religions and Chair of Global Religions and Philosophy, held an open research chat on Buddhist business ethics in the lower level of Reeves Library.

The conversation centered on how Buddhist beliefs and ethics are incorporated in business strategy, and how these concepts differ from what we consider “traditional” business. Cheung is currently writing a chapter on the topic for a book on Buddhist philosophy.

Buddhism, which originated in India, is globally recognized for its teachings of the Buddha, also known as dharma. Practices of the religion emphasize compassion, mindfulness, and ethical conduct as part of the journey to end suffering and spread the dharma.

Cheung explained that in Buddhist ethics, high status and monetary gain are viewed as means of accumulating karmic capital. More specifically, the money is reinvested in other operations to spread the dharma, such as building large gold statues in the mountains that are visible to everyone. Through this, they can continue building capital through the cycle of giving and receiving good karma.

He also mentioned that historically Buddhists have been well educated on how to handle money, both in material terms and in theory. Temples are known for rebuilding their communities by reinvesting in them through services such as loans, endowments, and insurance.

Though as Buddhists continue to explore capitalist ventures, the lines between actions and teachings blur. This leads to discourse among the Buddhists themselves, who seek to find a middle ground on what’s acceptable in pricing and the accumulation of wealth.

This scenario challenges corporate conduct in the West, where competition, profitability, and a free market are a few of the main elements that make up business culture. The assumption that “more is better” drives business operations, which naturally clash with the values of Buddhism.

While there is nothing wrong with Buddhists participating in the economy itself, says Cheung, accumulating wealth is thought to be out of ordinance with the dharma. Cheung quoted Sheng Yen, a Buddhist teacher, in his article, “Should Buddhists Invest in the Stock Market? Views from Contemporary Taiwanese Buddhists,” declaring that greed can turn “destructive.”

Cheung provided the recent example of Shi Yongxin, former abbot of the 1,500-year-old Shaolin monastery, who successfully integrated the temple’s functions into a global tourist attraction. In July, he was denounced from the temple and investigated for multiple breaches in monkhood, such as having mistresses and non-marital children, and participating in embezzlement. There has been no update from Shi since.

Buddhism sets strong expectations on how monks should conduct themselves; however, it contradicts the standards we hold for businesses in the West. While accounting for corporate social responsibility (CSR) is expected by the market, companies still thrive from unethical strategies, such as price gouging and concealing predatory conditions in their terms and conditions.

The differences in monetary relationships between faith and followers was also a highlight of the conversation. Under Christianity, greed is considered a sin, Cheung explained, and money is often misidentified as the “root of all evil.” Churches are usually subject to controversies around infidelity and other immoral actions, though they continue to run on donations. Thus arose the question: Should religious leaders be denied pleasure?

The lecture concluded with a mutual agreement that, regardless of the region or religion, such dilemmas are inevitable.

“Modernity comes with its issues, but none of them are new, just changing,” Cheung said.