Hiroshima Survivor Emiko Okada Visits Moravian To Share Her Story

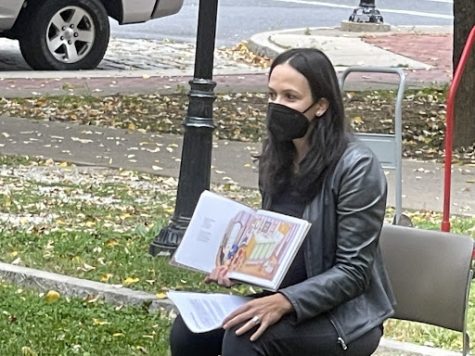

Okada telling her moving story alongside of translator Elizabeth Baldwin.

Emiko Okada visited Moravian College on Wednesday, Jan. 30, to share her experience of surviving the U.S.’s atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945.

Steve Leeper, founder of the nonprofit PEAC Institute who accompanied Okada, also spoke of the Institute’s Hibakusha Appeal, which calls for the elimination of all nuclear weaponry. Together, they aim to educate others on the catastrophic consequences of nuclear weapons in hopes of preventing future generations from experiencing situations similar to Okada’s.

In Prosser Auditorium, with Elizabeth Baldwin translating, Okada spoke in Japanese about Aug. 6, 1945. On that fateful day, the residents of Hiroshima, Japan, had been under an air raid warning until 7 a.m. When the warning lifted, 8-year-old Okada and her family went about their day as usual. Earlier that morning, Okada’s older sister had left for work in the city, where she made materials for the Japanese army.

It would be the last time Okada ever saw her.

Shortly afterwards, at approximately 8:16 a.m., an American B-29 bomber plane named Enola Gay dropped the world`s first atomic bomb over Hiroshima, which was less than 2 miles from Okada’s home. The last thing she remembers, Okada said, is seeing the bomber fly over the city followed by an intense white light before she was thrown to the ground by the intensity of the nuclear explosion.

Everywhere Okada saw people crying for help and water. While Okada suffered no external injuries, others were not so lucky, including some who were naked, their skin hanging off their bodies, exposing their bones.

Flames quickly engulfed her neighborhood. As Okada moved through the rubble, a young girl whose eyeballs hung from their sockets gripped her pant leg. Okada shook her off and kept moving.

Today Okada is reminded of that morning in August whenever she looks at the sunset. She explained that sunsets bring back the memory of that little girl and of Okada’s sorrow for leaving her — and all those neighbors — behind.

Eleven years after the attack, Okada said, her body felt weak due to the immense amount of radiation she had been exposed to. Eventually, she was diagnosed with aplastic anemia, a rare disease of the bone marrow. At the time there was no cure, but over time her cells restored themselves.

Eventually, Okada returned to school, even though she still felt very weak and oftentimes had to leave school in the middle of the day. Her classmates believed that she was simply lazy, not knowing that Okada was a survivor of the blast, because she didn’t have the visible external wounds that would have identified her as one of the “hibakusha.”

In Okada’s high school years, both of her parents died from the effects of the attack. Okada recalled her mother`s cremation. Normally, family members pick out what remains of their loved one’s bones from the ash and bury them. In the case of Okada’s mother, no bone fragments remained, because radiation from the blast had thinned and made them brittle. All that was left in the ash were shards of glass that had been lodged into her skin from the great force of the explosion.

Okada went on to live on her own for a few years. Having little money, she lived as frugally as she could. At 18 years old, she taught herself to sew and from there eventually earned a living selling the clothing she made. When she was 22 years old, Okada married and started a family, eventually raising two children.

Seven years ago, Okada developed stomach cancer. Nearly 100 percent of all “hibakusha” develop cancer in some form. A few weeks before coming to campus, she received news that her cancer had gotten worse. Due to her recent decline in health, Okada says that now more than ever she wants to share her story as often as possible in order to educate people on the tragedy that results from nuclear weapons.

Okada’s message of peace is simple and yet urgent enough for her to travel from Japan to Moravian College in what may be a final journey.

“War starts instantly,” Okada said. “Peace begins when you sit knee-to-knee and talk.”

David Riley • Feb 8, 2019 at 3:09 pm

Thank you so much for educating many people in this area of nuclear warfare and it’s immediate and long-term effects on mankind. Okada’s story of surviving such a nuclear Holocaust is just amazing and a miracle. I can’t believe she survived this long, and was able to raise a healthy family. She is definitely put here for a purpose to help educate people on nuclear warfare. Hopefully the world has learned from this and we will never experience this again. Thank youOkada.