WLVR News Director Jen Rehill Discusses Unusual News Coverage in an Age of Post-Objectivity Journalism

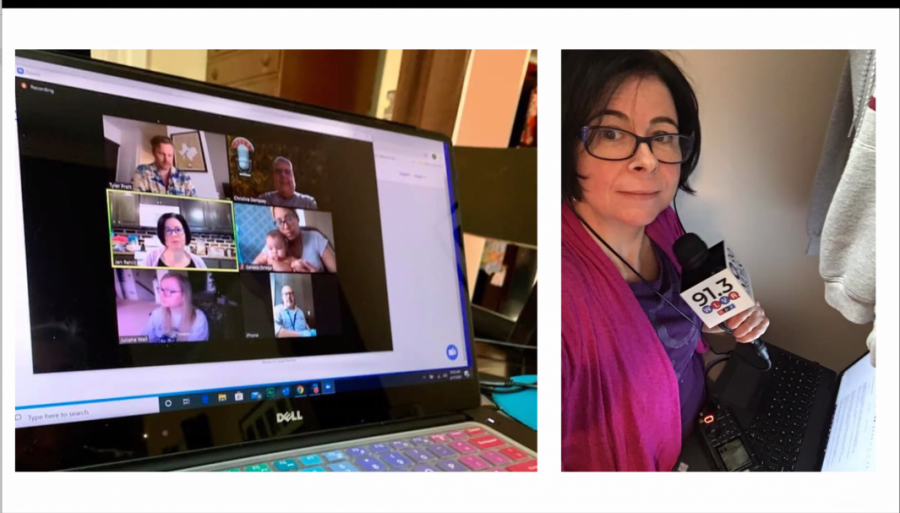

On October 5, WLVR News Director Jen Rehill connected with students via Zoom to talk about covering a presidential election in a pandemic, news objectivity, and what it is like starting and managing a local public radio station.

Rehill is currently the news director for WLVR radio of the Lehigh Valley. The station (91.3 FM for anyone who is interested in listening) is part of the Lehigh Valley Public Media organization. Other members of the organization include PBS39 and WLVTV, both of which are partnered with Lehigh University for a local news initiative. The radio station is partnered with NPR, who helps to provide national news stories for the radio station.

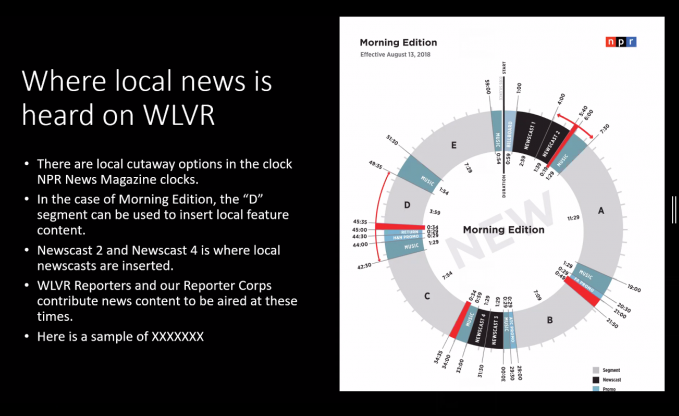

The station is a mix of WLVR-written local news stories that they produce and broadcast, as well as segments from NPR for national news, WLVR stories about state news, and segments dedicated to local partners who can broadcast what they please — sometimes it’s music, news segments, or something entirely different. However, as Jen Rehill mentioned, it’s the only full-service information station of the Lehigh Valley.

Jen Rehill had a bit of an unusual beginning to public radio. She was a liberal arts psychology major at Rosemont College, PA, but she was not sure what exact career path she wanted to follow.

“After working a couple non-career-track jobs, I decided to travel around and focus on what I wanted to do,” Rehill explained. “That’s when I moved to England in a tiny town in a house that didn’t even have a TV. All I had was a radio, and that’s when I fell in love with it.” From then on, she moved back to Philadelphia with the sole goal of working in public radio.

Rehill was instrumental in starting WLVR. In the beginning, she partnered with Lehigh University to begin producing and broadcasting stories for the radio station.

“My goal was to model it after NPR, but focus on more local stories,” Rehill explained. “I wanted to amplify diverse voices and look at the interests of my community — which is something that national news can’t provide.”

So with this new partnership, Rehill collected a team and officially launched WLVR in late 2019. The team started with a small goal of four abbreviated newscasts a day and planned to slowly expand from there.

“But then March 2020 hit,” Rehill said, “and the pandemic came to us. We knew the community needed news, and we needed to start expanding our broadcasts — and fast.” In just a few weeks (at home working remotely no less), the radio expanded from four newscasts to a full sixteen unabridged full coverages a day.

“It was strange,” Rehill said. “I ran an entire radio station from my kitchen table since March. I was recording newscasts in my daughter’s closet, which became my makeshift recording studio.”

And since then, Rehill and her team have been working round the clock trying to keep up with local, state, and national news as it unfolds.

But Rehill was clear about some of the struggles that she faces in covering such a news-flooded year.

First, she mentioned the struggles of what she calls the “post-objectivity journalism age.”

She explained that in years past, people expected journalists to stay absolutely impartial, letting no personal bias show through their reporting. However, many journalists are starting to move into a belief that reporters should be allowed to give their opinions in the media, both in their private and professional lives, mainly because it is believed to be impossible to completely distance yourself from all of your conscious and unconscious biases.

“Reporters in the past were not allowed to post anything on their social media about things like Black Lives Matter or political opinions,” Rehill said. “It was all in the pursuit of staying objective. But younger reporters with a different relationship to social media than the previous generation started to really question this philosophy, especially when Black Lives Matter became more visible in the summer.”

She mentioned an incident in which she talked with one young reporter in particular who felt strongly about supporting Black Lives Matter on his personal social media accounts. He felt it was wrong that he couldn’t speak his opinion just because he was a journalist.

“He was Black,” Rehill said. “He and his family were impacted by the movement. It was not something that he could remove from his family and his own identity, and he felt compelled to speak out for himself. I started to question the idea of objectivity right then and there.”

This conversation led to her second struggle of being a news reporter: reporting on political news.

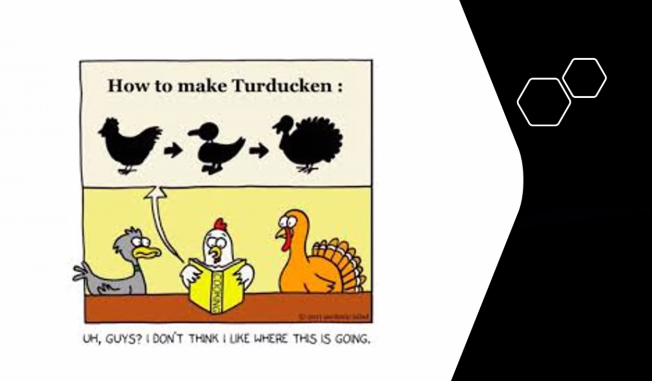

“In the radio business, we call political news reporting the Great Turduken,” Rehill joked. “This summer, we were reporting on an election happening during a great social movement happening in a worldwide pandemic.”

Everything that she and her team were reporting on were related to each other, and there was just so much information to cover that it was hard to weed out exactly what to report on. “Our greatest challenge,” she explained, “is cutting through the noise. So many stories and articles are being told and written right now that people can’t keep up. They just want to know, ‘What’s the real story?’” She noted that how most of the general public is tired and often distrustful of the media, and said she is constantly “fighting an uphill battle” to make her and her team believable to their audience.

“It’s a challenge to stay on top of it,” Rehil said. “But public media coverage is a public service. It’s our job. We need to give the information and let people make their own decisions.”

As for young and upcoming journalists, Rehill had some advice. In regards to utilizing a finite amount of time for practically unlimited news stories, she advises journalists to focus on stories that they are interested in. “Follow the story,” she said. “Follow the story that you would call up your friend on the phone and tell them about, because that’s what other people are interested in as well.”

Rehill’s talk was sponsored by a number of Moravian organizations, including the English department, Moravian’s student Political Awareness Club (aka PAC), the political science department, and the Career and Civic Engagement Center. The night was hosted by political science professor Dr. Kristina Haddad, and was attended by students and professors alike.

To listen to WLVR radio and catch a glimpse of what Jen Rehill is producing, tune to 91.3 FM on any local radio station, listen live via WLVR.org, livestream WLVR-FM via the free WLVR mobile App, or listen on your smart speaker by first telling “Alexa, Enable WLVR News Skill” and then simply say “Alexa, Play WLVR News.”