A Necessary Spotlight On War Literature: Moravian University’s Writer’s Conference on the Voice of War

This year’s Moravian Writer’s Conference, titled Voices of War, featured the topics of war literature and veterans’ experiences in the literary world.

Many of the workshops and keynote discussions were from former veterans helping to process war for the general public and pointing out the ways in which war balkanizes populations. Dr. Liz Gray, visiting assistant creative writing professor at Moravian, and Dr. Kate Brandis, professor of writing and geology, organized this year’s event and helped coordinate many of the veteran workshops and panels.

Jenny Pacanowski conducted a reintegration workshop for the general public. Her work as a director for a reintegration program for female veterans and her deployment in Iraq has helped facilitate the difficulties of war to the general public.

Her workshop included storytelling and inviting the general public to write from personal experiences, not exactly pertaining to war, and encouraged attendees to speak on a specific memory if they so choose. The stories of the workshop were strictly confidential but showcased a collage of enlightened experiences from all age groups and really emphasized the importance of storytelling in light of personal turmoil.

Army veteran Eric Fair hosted a roundtable and Q&A with guest panelists, such as author Chad Frame, Moravian University’s Executive Director of Veteran And Military Services Marilyn Kelly-Cavotta, and veterans advocate and Moravian’s Special Projects Director Carole Reese. Fair himself is the author of “Consequence: A Memoir,” a reflection on morality and allegiance to a nation.

Each panelist relayed the situations they found themselves in the aftermath of their time in the army. Chad Frame detailed writing and poetry with an emphasis on emotional truth. Moreover, he wanted to capture the veteran experience and the experience of dying through lofty language.

Kelly-Cavotta said she is the child of a veteran who didn’t open up at all, contributing to a dysfunctional family from her father’s PTSD. She also talked about being in and out of the military, getting her master’s in social work, and eventually coming to Moravian. By sharing her story, she sought to bridge the divide that exists between the civilian world and the militant world.

Additionally, her National Guard enlistment was a huge part of her life and contributed to her isolation from active duty colleagues, a type of “two-fold isolation” as she put it.

Carole Reese also elucidated on the National Guard not living on a base, as well as the gossip and lack of understanding that spawns from how local it is. She explored her own story of being a veteran wife and illustrated the harrowing tale of her husband’s being a victim of a glass factory disaster in Ramadi, Iraq. She described herself as a talker and as being very open to talking about her feelings to “make things a bit better for veterans and their families.” According to her, stoicism can be very damaging for veterans and veteran families, which was why she felt the need to use her voice freely.

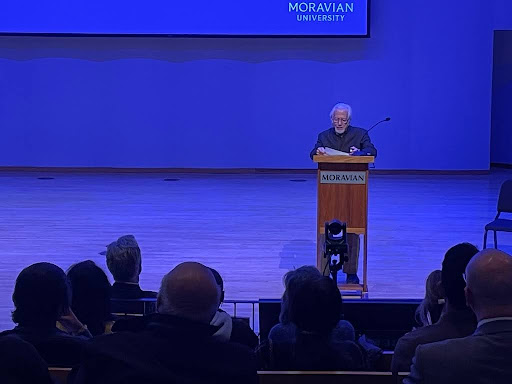

Writer and former soldier Matt Gallagher gave a keynote speech pertaining to war literature.

He began his speech by recalling an encounter in 2017 with a famous author [unnamed] who posed the question, “What more could be said about war?” and implying that war literature has become contrived. Gallagher answered this by saying how no one is conscripted into uniform anymore and war literature will always be a relevant artifact of the times.

He also mentioned Tim O’Brien, a Vietnam veteran and author of the acclaimed war novel, “The Things They Carried,” and the way war is told anew for every generation. From personal experience, watching 9/11 unfold inspired him to be an ROTC cadet with an idealist notion of wanting to serve and seeking to do something just. His 15 months in Iraq influenced his gravitation towards literature, even drawing a parallel from his ventures to George Orwell’s idea of “the dirty work of empire.”

To create good war literature, Gallagher advised following the ideas of Faulker and the human heart and what it conveys. Good literature must transcend into weighty grey areas like Leo Tolstoy’s “War And Peace,” which shows loftiness in the moments of war or Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun,” which describes the intricacies of the Nigerian war. Additionally, Fair’s “Consequence” explores the full effect of the Iraq war with a transcendence into morally grey sectors of the war. He implored writers to treat war as a subject, not an identity, and to ensnare mortality and forgiveness.

Gallagher also explored the value of having anti-war sentiments and reasoned with this by describing war as a choice and not something inevitable or uncontrollable like a natural disaster.

An example he brought up was the Russia-Ukraine conflict, noting Russia’s choice to invade Ukraine. He mentioned his training of local civilians in Ukraine and described it as some of the most fulfilling work he had ever done. “Americans can’t perceive the [Ukrainian] survival against Russian snipes,” he said, “People matter more than ideology.” The invasion of Ukraine has been its own conflict, not an American war at all, and also not to be compared to other wars such as Afghanistan, Iraq, or Vietnam. According to Gallagher, in 2023 America, sometimes, “There are states of affairs worth fighting for and as citizens of a republic, we make sure it’s worth it.”

He emphasized how writers of war should not let people forget and that they have a civic responsibility in showing others how to remember to. He also read an excerpt from his upcoming book “Daybreak” which is loosely based on the events in Ukraine in February 2022.

Writing about trauma, he asserted, helped to compartmentalize it and showed how conflicts such as the one in Ukraine are not black and white. Mentioning that he is not a fan of the military-industrial complex, he still acknowledged that there is a genocide going on and we as thinking people can learn from the past and see that a sovereign democracy such as Ukraine does not deserve to be occupied. He concluded his keynote address by noting how the theme of war has been changing ever since the disappearance of the draft and how war can feel like a foreign concept, depending on the generation, but that awareness is still a significant component in compartmentalizing it.

Gallagher also conducted a workshop on imagination and history and helped attendees process the courses of war and change. He helped attendees examine how change enhances literature and the ways in which storytelling interacts with historical influence and societal evolution. Some of the works he explored include James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” and George Orwell’s “A Hanging” and “Shooting An Elephant.”

Writer Andria Williams held a virtual workshop with a concentration on the stories of military spouses. Pulling from her own novel “The Longest Night,” Williams opened the conversation for the often-forgotten perspectives of military spouses and invited other attendees to think about the power of secondhand experiences.

Marine wife Lisa Stice spoke on her own lofty experiences in her poetry collection titled “Forces” and illustrated the emotional and psychological turmoil that came with being a military spouse. Gail Hosking Gilberg detailed her experience as the daughter of a military father who died in Vietnam in “Snake’s Daughter” and the collateral damage of war in “Retrieval.”

Steven Nolan’s Voices of War workshop reflected on trauma, traumatic responses, and the resilience of victims of war using poetry and journaling. Much of his workshop focused on the different paths for processing trauma, mental health interventions and the road to recovery. He also highlighted the difference in cultural backgrounds that heavily affect the psychological turbulence created by war.

This year’s conference was an enlightening venture into bridging the gap that war has created between the general public and veterans. By exploring the sectors of war literature, many of the workshops provided a safety net for both groups to utilize writing and helped dispel the misconceptions of war and the miscommunications with soldiers.