Sociologist Eric Klinenberg Urges Social Solidarity During Pandemic

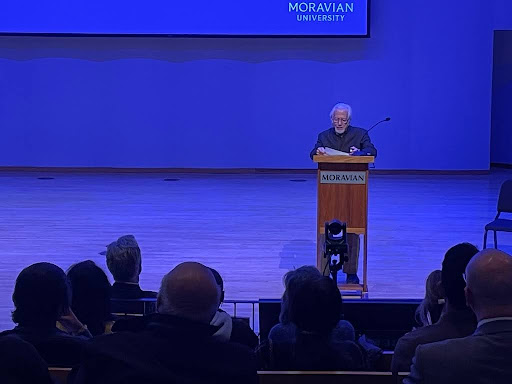

On Wednesday, April 22, Moravian College welcomed author and sociologist Eric Klinenberg to talk about spatial inequality and social solidarity for the Moravian InFocus Symposium ‘20.

The Symposium, titled “Scarcity, Poverty, and Inequality,” was dedicated to the late Dr. John Reynolds, a beloved professor of political science at Moravian for more than 40 years.

It brought together about 140 students, faculty, and guests via Zoom.

The need for physical separation was one of many talking points for Klinenberg.

His presentation, titled “Spaces of Equality: Facing a Pandemic,” warned against extreme social isolation. He claimed that in the midst of the coronavirus crisis, isolation could ostracize underprivileged communities when they most need a helping hand.

Klinenberg sought to rephrase social distancing as “physical distancing” and urged attendees to practice it alongside an additional duty, one he called “social solidarity.”

“Social solidarity means the recognition of the extent to which we are interdependent,” he said. “It means recognizing that we are embedded in webs of interdependence, and our fate is linked to the fate of the people around us.”

Klinenberg understands these social webs well.

A professor of sociology at New York University, Klinenberg has authored several acclaimed books on the social consequences of various institutions and events, including “Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life” and “Fighting for Air: The Battle to Control America’s Media.”

Klinenberg has also written sociological articles for Wired, The Atlantic, and The New York Times.

During his presentation, Klinenberg drew specific comparisons between the COVID-19 pandemic and the week-long heatwave in 1995 that killed over 700 residents of Chicago, which he wrote about in his first book, “Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago.”

“As the heat moved up to the city of Chicago,” Klinenberg said, “scientists warned it could be dangerous, but a lot of the leadership in Chicago went on vacation.”

He went on to say that “the city forgot/decided not to follow the heat emergency plan in the books. Thousands of people got sick and went to the emergency room, so much so that some of the hospitals had to shut down.”

However, Klinenberg stressed, the people most vulnerable to the heatwave tended to be older, impoverished, and disproportionately African American. A majority of these people also had preexisting health issues that the heatwave later made lethal. These facts spurred a revelation in Klinenberg.

“We sometimes think of disasters as these unusual aberrations from the norm, when in fact, this disaster in Chicago was just making visible a series of social conditions that were present every day but difficult for many people to perceive.”

By analyzing both the worst-hit and most resilient communities, Klinenberg discovered a direct correlation between a community’s access to social support and its number of heat-related deaths.

The worst-hit communities appeared “institutionally abandoned,” filled with broken-down sidewalks, decaying parks, and closed churches. They lacked public gathering spaces, and as a result, residents were conditioned to isolate themselves. When the heatwave hit, these residents braced themselves in their un-air-conditioned homes as usual, with disastrous results.

Resilient communities, meanwhile, possessed a “physical vibrancy,” as evidenced by their well-maintained parks, libraries, and other public spaces. The quality of these spaces encouraged daily socialization; people knew each other more intimately, and thus, during the heatwave, any person who fell ill would likely be noticed and receive help.

“The places that have a robust social infrastructure,” Klinenberg said, “have a social process that keeps people alive.”

Klinenberg believes this conclusion holds true for the current pandemic as well.

As the coronavirus runs its course, primarily through working-class communities, accessibility to social support will influence the number of deaths. Unfortunately, the virus will likely devastate communities with a crumbling, social infrastructure more so than affluent communities or communities with a thriving, social core.

While he acknowledged the need for physical separation, Klinenberg also emphasized the need for social solidarity. Keeping in contact with members of the community, checking on neighbors, and spreading healthy practices can save lives in the long run.

Even during a crisis that forces separation, history shows that people must stay connected to survive and thrive.

Sonia Aziz • May 20, 2020 at 6:03 pm

I enjoyed reading your thoughtful coverage of the keynote talk. Nicely done!

Joyce Hinnefeld • May 2, 2020 at 1:00 pm

Thank you for this excellent coverage of Klinenberg’s talk, Tim! It was an inspiring event for so many of us, and you’ve captured his points beautifully here.